Graves of unknown soldiers in the national cemeteries are commonplace and marked in many different ways. While the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in the Army’s Arlington National Cemetery is the most culturally recognizable unknown grave, VA national cemeteries also have less grand examples of unknown burials that span the early 19th century through the Korean War.

While most are marked with the same upright headstone used to identify other fallen soldiers of their era, some feature more unique designs. At St. Augustine National Cemetery in Florida, for instance, three coquina pyramids erected in 1842 mark the collective reinternment of nearly 200 soldiers killed in the Florida Indian Wars (1835–1842). At San Francisco National Cemetery, a rough-hewn granite American eagle marks the gravesite of 571 unknowns relocated from other parts of the cemetery in 1934. The most common form of unknown marker, however, is the simple 6×6-inch stone that adorns the graves of thousands of Civil War soldiers.

The Civil War led to the first official policy for marking graves of unknowns. In the war’s aftermath, 46 percent of the 300,000 Union soldiers and sailors buried in 74 national cemeteries were unidentifiable. That figure was even higher for the U.S. Colored Troops, the U.S. Army’s official name for its segregated Black Civil War regiments. About two-thirds of their dead were never identified. Nonetheless, the federal government endeavored to mark the graves of all who gave their lives while serving in the Union Army and Navy.

During and immediately after the Civil War, the U.S. Army’s Office of the Quartermaster General was responsible for locating, gathering, and, whenever possible, identifying the remains of fallen U.S. troops. The Army kept meticulous records as these graves were found and the remains recovered. If the decedent was reburied in a national cemetery, information was recorded in a permanent ledger and the grave was marked with a temporary headboard. Rotting wooden headboards and Southern antipathy toward Union graves erased the names of innumerable soldiers. The ledgers eventually contributed to the federal government’s publication of Roll of Honor, a multi-volume series of books aimed at informing families and friends of burial locations.

It took the federal government until 1872 to finally settle on the two types of headstones that would permanently mark the Union dead. Graves containing identified servicemembers received an upright marble slab similar in aesthetic to today’s headstones. For unknowns, the Quartermaster General’s office ordered that “the headstone was to be a block of marble or durable stone 6 inches square, and 2 ½ feet long, the top and 4 inches of the sides of the upper part to be neatly dressed and the number of the grave to be cut on the top, the block to be firmly set in the ground with the top just even with the top of the grave.”

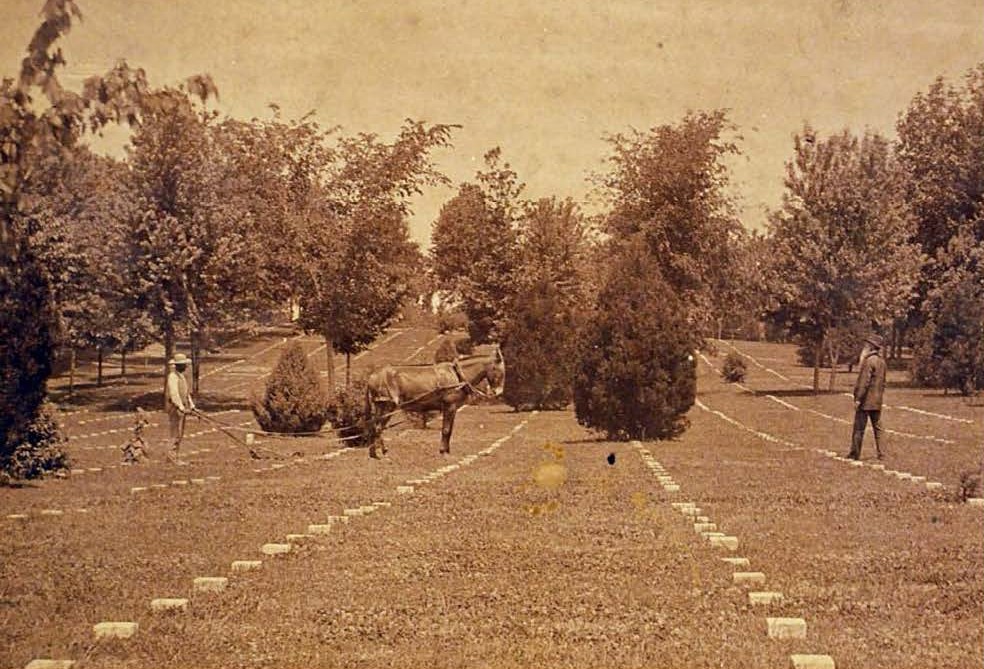

These small 6×6 markers created a unique landscape specific to Civil War-era national cemeteries. The squat squares, nearly flush to the ground, numbering in the hundreds and arranged somewhat haphazardly, stood in stark contrast to the rows of upright headstones for their identified comrades in arms. The use of the 6x6s, however, was short-lived. To make the national cemeteries more uniform in appearance and probably for maintenance reasons as well, the Army in 1903 decided to stop furnishing blocks for the graves of the unknown dead and issued upright headstones instead. The markers were identical to those supplied for the known dead but the inscription on their face reads:

Unknown

U.S. Soldier

The new policy did not mean the immediate removal of all 6x6s in the system. They were only replaced with upright markers when their condition deteriorated. Rather than discard the stones, however, some cemetery caretakers appreciated their utilitarian shape and found other ways to use them on the grounds.

For instance, nearly 100 6x6s were recently discovered at Annapolis National Cemetery in Maryland that were being used for landscaping and drainage purposes. Old maintenance ledgers showed that the markers had been removed and repurposed in the late 1950s, a practice the Army at the time considered resourceful rather than disrespectful. The historic 6x6s were subsequently taken from Annapolis and carefully stored at Baltimore National Cemetery for NCA historians to evaluate and assess. Four of the most intact stones were accessioned into the NCA Artifact Collection and the rest demolished, as is now the standard way to dispose of unserviceable grave markers.

To preserve the historic landscape of the national cemeteries, NCA has reversed the Army policy on removing 6×6 markers in poor condition and now replaces them in kind.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.