On July 4, 1948, the Central Blind Rehabilitation Center at the Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital in Illinois admitted its first trainee. The Hines Center ushered in a new era of care for blinded Veterans. Yet, its opening was nearly three decades in the making.

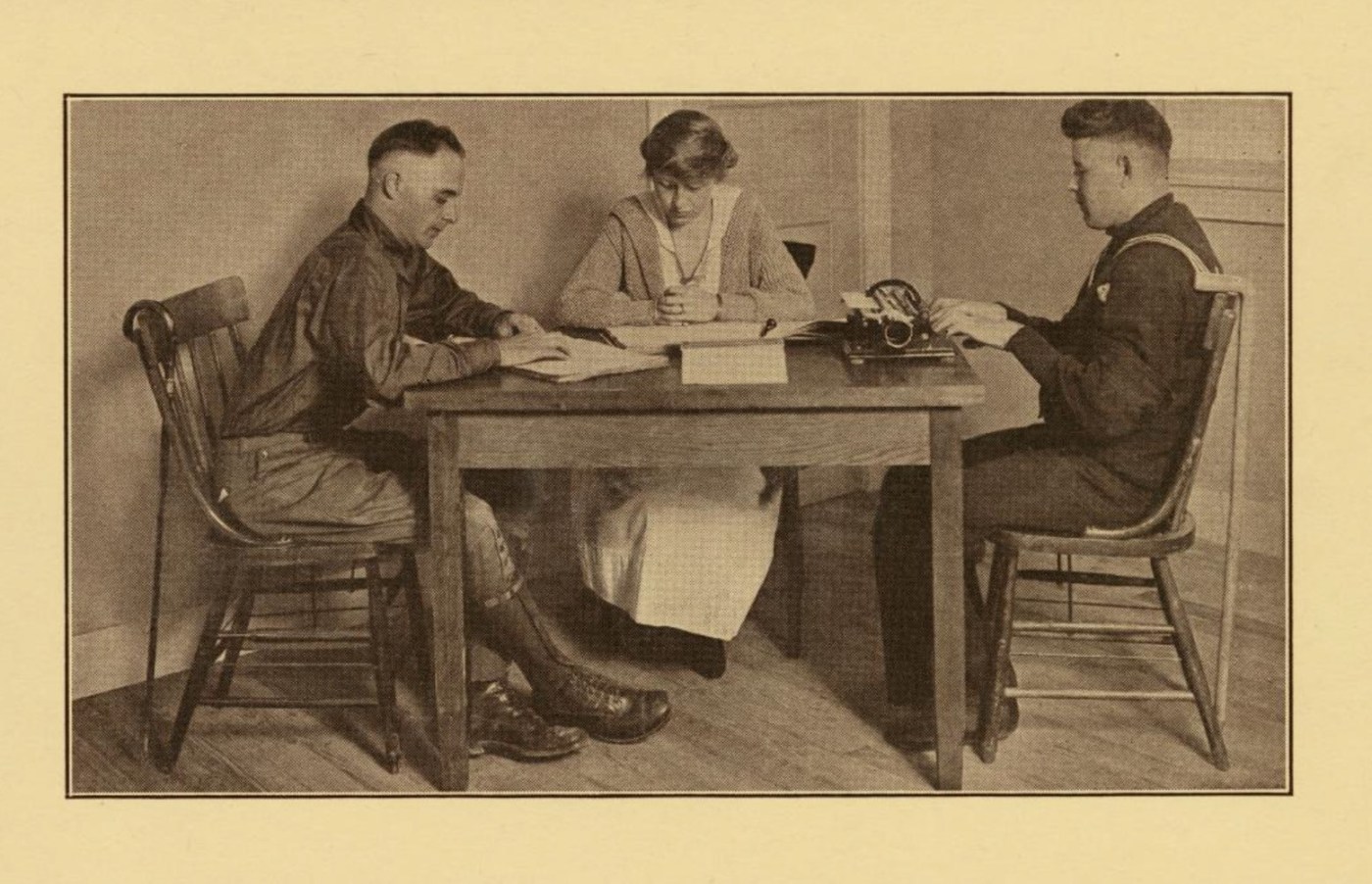

Formalized federal care for blinded Veterans dates back to 1917, with the opening of Army General Hospital #7 near Baltimore, Maryland. Colloquially referred to as Evergreen, the hospital offered vocational training to World War I Veterans with various levels of vision loss to help them adjust to life and find productive employment. Evergreen’s curriculum had over three dozen classes for Veterans to choose from, including woodworking, salesmanship, machine shop practice, bookbinding, beekeeping, and insurance sales. What the rehabilitation program at Evergreen did not offer, however, was specialized training in independent movement and travel. Students were expected to pick up those skills without formal instruction as they participated in the program’s daily activities. Although the total number of American Veterans blinded in World War I is uncertain due to incomplete records, several hundred appear to have been treated at Evergreen. The facility was transferred to the newly established Veterans Bureau in 1922, but a myriad of budgetary concerns combined with a decline in both patient numbers and qualified staff led to Evergreen’s closing just three years later.

The need to provide rehabilitative services to vision-impaired Veterans returned with the United States’ entry into World War II. According to a VA study, approximately 1,700 service members were completely blinded in the war while over 20,000 suffered some degree of vision loss. In 1943, the Army created specialized rehabilitation programs for visually impaired soldiers at hospitals in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and San Francisco, California. The Navy established its own program for sailors with vision loss at the Philadelphia Naval Hospital. It soon became clear, however, that additional rehabilitative services would be required to help these men transition back into civilian life. VA Administrator Frank T. Hines collaborated with the secretaries of the Army and Navy and the chairman of the War Manpower Commission to produce a set of recommendations for their care. The recommendations, approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on January 8, 1944, made the Army responsible for the “social rehabilitation” of visually impaired military personnel and placed VA in charge of vocational training.

To fulfill its obligations, the Army, in conjunction with VA, opened the Old Farms Convalescent Hospital in Avon, Connecticut, in June 1944. There, patients learned to read Braille, perform daily tasks, and navigate independently. The staff created a wooden model of the hospital complex for patients to study so they could walk around the campus unaided. For off-site trips, they were given a new type of walking cane that had been designed by Army Sgt. Richard Hoover while he was working at the Valley Forge hospital. Although not blind himself, Hoover had previously taught at the Maryland School for the Blind and had a deep interest in helping the blind live independently. His metal cane was longer, lighter, and a better conductor of sound than the wooden canes previously in use. He also developed a new method of employing the cane, tapping it from side to side in an arc in front of the trailing foot to identify obstacles.

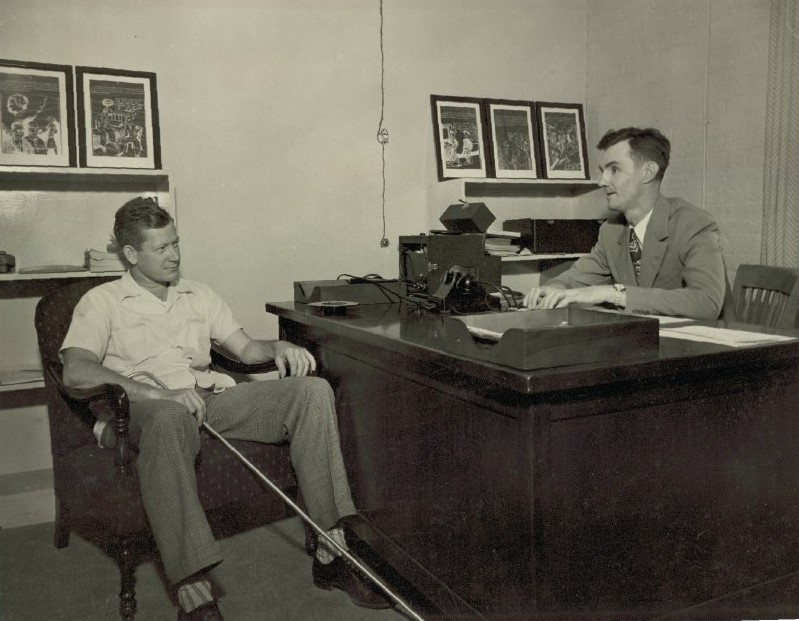

After the war, the Army closed the Old Farms Convalescent Hospital, leaving the care of blinded Veterans entirely to VA. In 1948, VA opened the Central Blind Rehabilitation Center at the Hines VA Hospital outside of Chicago, Illinois. Major General Paul R. Hawley, M.D., VA’s medical director, picked Hines because he wanted to integrate the center into the large Medical Rehabilitation Department already in place at the hospital. VA recruited former staff from the Army’s facilities for blinded soldiers to continue their work with the vision impaired at the new center. Notable among them was Russell C. Williams, who lost his sight during the fighting in Normandy in 1944. He received treatment at Valley Forge General Hospital and afterwards served as a counselor there. Williams became the center’s first chief and he emphasized Orientation and Mobility training for the Veterans who enrolled in the rehabilitation program at Hines. Although most of his staff were sighted, they, too, learned these skills by navigating the hospital grounds blindfolded during their training. Richard Hoover also joined the staff at Hines where he refined and taught what came to be called the “Hoover method” for using the long cane. The technique he pioneered remains the standard today. In 1953, VA produced a promotional film titled “The Long Cane” that featured demonstrations of this technique in both indoor and outdoor settings while also showcasing the therapeutic services the center offered.

For almost two decades, the Hines Blind Rehabilitation Center was the only one of its kind in VA. Its success and the increased demand for blind and low vision training led VA to add two new centers in the late 1960s. The number has since grown to thirteen. These centers along with over 50 outpatient clinics now treat tens of thousands of Veterans annually who have experienced vision loss.

By Jordan McIntire

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, VA History Office Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.