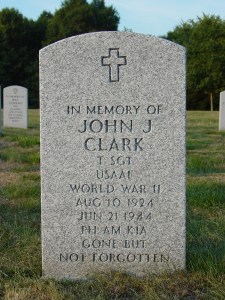

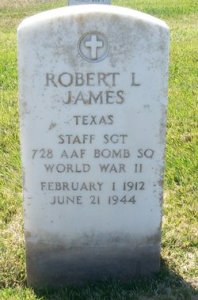

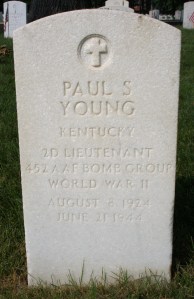

Crew members lost later interred in National Cemeteries

Tech Sgt. John Clark, Staff Sgt. Robert James, Sgt. Willard Johnson, and 2nd Lt. Paul Young. These are the names of four men interred in four different national cemeteries. Though they now rest hundreds of miles apart with no relation immediately obvious, they are all connected through a single tragic event. One that occurred during World War II in 1944.

On the morning of June 21, 1944, 20 men boarded two B-17 Flying Fortress bombers in Norfolk, England. Both crews belonged to the 728th Bomb Squadron, 452nd Bomb Group. They had arrived at Deopham Green airfield in January and flew mostly strategic bombing missions over Germany. They also supported the D-Day invasions on the coast of Normandy.

Clark, a twenty-year-old from Virginia, enlisted in the Army Air Forces after the United States entered World War II. He served as a radio operator on the B-17 numbered 42-102662 (#662). Serving alongside him on the #662 left waist gun was James, from Texas, and eight other men.

While the crew of the #662 prepared for departure, so did the crew of the B-17 named Little Colonel. The tail gunner, Johnson conducted his pre-mission checks. He was a twenty-eight-year-old auto mechanic from Chicago and a first generation American born to Swedish parents. That morning he boarded the plane alongside Young, a nineteen-year-old bombardier from Kentucky, and eight other crew members.

Both planes took off and joined a bombing formation before heading over the North Sea towards Berlin. Their intended target was an aircraft engine factory. The group reached their target at about 10:30 a.m. and both #662 and Little Colonel released their bombs. During the mission, Little Colonel took some damage from flak shot from anti-aircraft guns on the ground but remained operable. The entire group turned and began heading towards the rally point designated a few miles northwest of Berlin.

About ten minutes later, as the group approached the rally point, #662 and Little Colonel collided.

The B-17 crewed by Clark and James made a right turn entering the path of Little Colonel. When the two planes made contact, #662’s tail broke off and entered into a tight spiral towards the ground. Little Colonel, already damaged by flak, broke apart.

A pilot from another bomber in formation observed #662 as it spiraled downwards about 20,000 feet before losing sight of it. He later noted that “it seemed impossible for anyone to bail out.”

Meanwhile, a few parachutes deployed from Little Colonel after breaking apart.

From the ground, German civilians, military, and police watched as the two planes came down near Rheinsberg. The rural police hurried to secure the crash site of #662 where they found one survivor, Staff Sgt. Edward Koster. He was a twenty-year-old from Rochester and served as the plane’s tail gunner. He was separated from the rest of #662 when the tail broke apart. He was taken prisoner and transported to the town of Neuruppin.

No other crew aboard the #662 survived. The remains of seven crewmen were found at or near the wreckage. One was taken to the nearby town of Beerenbusch where he was buried in the community cemetery the next day. The other six members were buried in Kleinzerlang’s municipal cemetery.

The two others from #662 were not discovered until later. German forces suspected that they may have attempted to escape. However, a German civilian discovered the remains of Clark a few days later in a fir forest. A few weeks later, James was found by a lake. Both were buried in the Beerenbusch cemetery.

Of the ten crew members of Little Colonel, only four survived. Two of them suffered broken right legs and another had received a cut on his head. They too were captured almost immediately after crashing and were taken to Neuruppin as prisoners joining Koster. The remaining crew of Little Colonel were buried in Beerenbusch alongside three of their comrades from #662.

In total, fifteen of twenty crew members perished that day. These are their names:

B-17 #662

- 2nd Lt. Edward B. Armm

- 2nd Lt. William H. Stooks

- 2nd Lt. Glen E. Swing

- Flight Officer James E. Dozier

- Tech. Sgt. Arthur C. Kaule

- Sgt. Joseph J. Ostrander

- Staff Sgt. George A. Thut

- Clark

- James

Little Colonel

- 2nd Lt. Richard F. Dean

- Young

- Tech. Sgt. Frederick W. Thomas

- Tech Sgt. Edward J. McGrath

- Ssgt. Richard V. Graham

- Johnson

The five survivors taken prisoner were: Koster, 2nd Lt. Harold Lerum, 2nd Lt. Melvin Van Gundy Jr., Sgt. George M. Slossman, and Sgt. Kenneth L. Salsbury.

After the war ended, efforts were made to recover the American remains buried overseas. The American Graves Registration Command (AGRC) launched an investigation in towns surrounding where #662 and Little Colonel went down to identify and locate all fifteen men who died that day. Through cooperation with local civilians, the AGRC were able to accurately locate all but one crew member: Clark.

In 1945, as Soviet forces pushed into Germany, many Soviet soldiers were also buried in the Beerenbusch cemetery. When the war ended, they too attempted to return the remains of their service members home. Because Beerenbusch lied in Soviet territory after the war, their military disinterred graves at the cemetery first. According to the German civilians interviewed by AGRC, the identification bracelet and cross placed at Clark’s grave went missing during the disinterment. Therefore, it was impossible to make a positive identification on his remains.

Today, Clark has a memorial marker in Gerald B.H. Soloman Saratoga National Cemetery. Three other members of the #662 and Little Colonel also rest in one of three different national cemeteries. James is interred in Golden Gate National Cemetery, Johnson rests in Rock Island National Cemetery, and Young is buried in Zachary Taylor National Cemetery.

By Kenneth Holliday

Program Specialist, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."