On October 6, 1917, six months to the day after the United States declared war on Germany, Congress approved an ambitious plan to remake the benefits system for the millions of men being mobilized for military service. The bill, which amended the War Risk Insurance Act of 1914, included compensation for injury or death in the line of duty, as previous benefits laws had done. But the legislation also broke new ground by offering a supplemental allowance for enlisted personnel with dependents, medical care and vocational rehabilitation for the sick and wounded, and low-cost insurance for all who chose to buy it. In its entirety, the 1917 War Risk Insurance Act sought to ensure the welfare of service members and their families both for the duration of the conflict and far into the future.

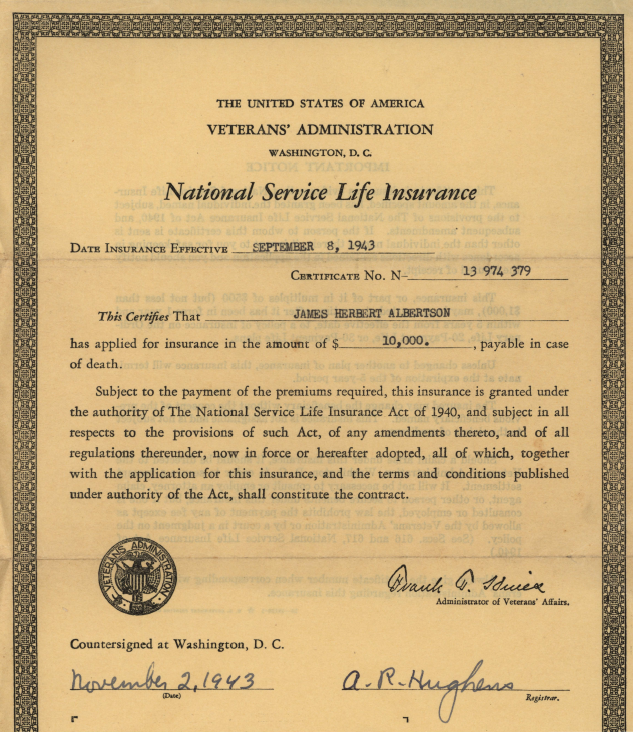

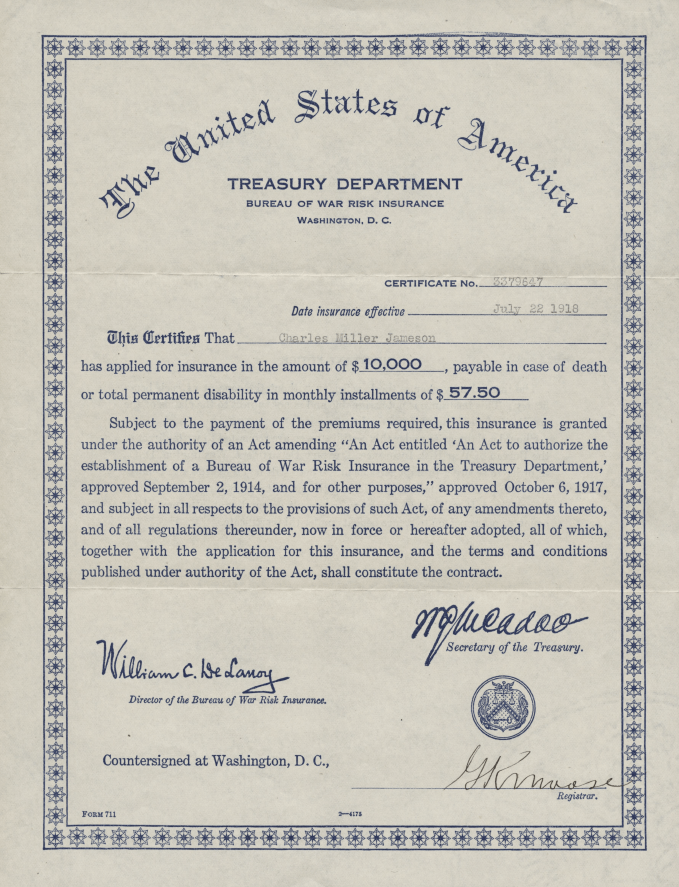

The insurance program was the most novel part of the new benefits package. Assistant Treasury Secretary Thomas B. Love lauded it as “the most liberal provision ever made by any government in the history of the world for its fighting forces in time of war.” The bill allowed military personnel to purchase up to $10,000 in yearly renewable insurance from the government covering them against death or total disability, regardless of cause. These short-term policies could be converted after the war into various types of permanent insurance plans similar to those marketed by commercial companies.

The U.S. government entered the life insurance business in large part because private insurers balked at taking on the risk. In July 1917, Secretary of the Treasury William G. McAdoo convened a conference attended by over 100 insurance executives. Only one firm, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, was willing to insure members of the armed forces but at more than seven times the normal premium rates. The insurance company representatives voted overwhelmingly in favor of letting the government proceed with its own plan of insurance. The program that became law under the War Risk Insurance Act set premiums at peacetime levels, leaving the government to absorb the “excess mortality and disability cost resulting from the hazards of war.”

McAdoo and others believed the state had an obligation to offer affordable insurance to the citizens who answered the call to service, whether they were volunteers or draftees. Such coverage would provide soldiers and sailors with additional financial protection for their loved ones should they come to harm. However, those who championed the insurance program had another goal in mind, too. They wanted to avoid the enormous costs of the service pensions granted to Union Veterans after the Civil War. In 1890, Congress made most surviving Union Veterans eligible for a pension provided they had served at least 90 days. The number of people collecting a pension almost doubled in just a few years and spending on benefits exploded. Over the next two decades, the government routinely devoted 25% or more of its annual budget to military pensions.

Reform-minded officials like McAdoo saw government insurance as the ideal substitute for another exorbitantly expensive service pension plan. The convertible policies, if carried into civilian life, would provide for Veterans in their later years when they were too disabled to work or for their families after they died. A $10,000 policy furnished the beneficiary with a monthly income of around $57.50 over a 20-year period, which was roughly equivalent to what the median household earned at the time. Equally important, the costs to the government would be minimal. Once death and disability claims returned to normal levels after the war, the program would largely be funded through Veterans’ own premium payments.

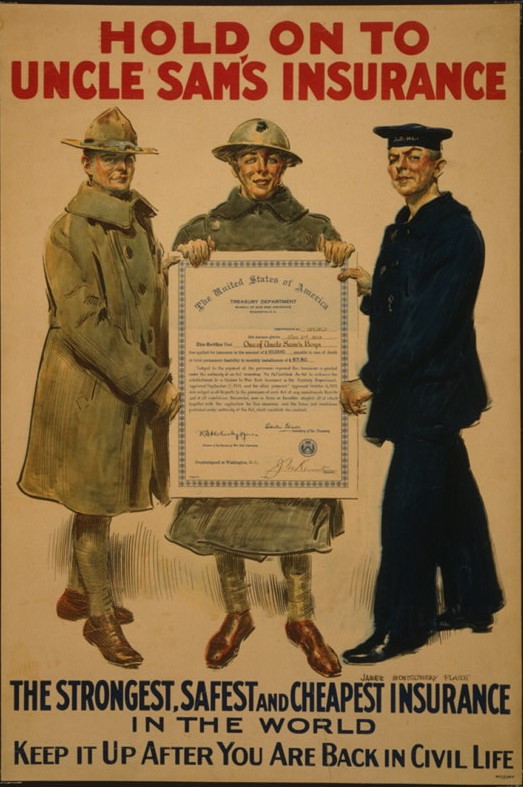

Despite the newness of the benefit, the War Risk insurance proved to be enormously popular. The Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the Treasury Department agency placed in charge of the program, launched a massive outreach effort to educate service members about the insurance plan. Towards this end, the government printed and distributed 5 million copies of the War Risk bill and more than twice that number of insurance applications. Representatives from the military and the Red Cross visited recruits in stateside training camps. Army personnel trained by the bureau to act as insurance agents were also sent overseas to deliver their sales pitch to troops in England and France. Some intrepid Army agents even ventured to the front lines to collect applications from soldiers on the eve of battle.

Within a year, the bureau had received over 4 million applications for insurance. An estimated 90 percent of those in uniform elected to purchase a policy that was worth on average $8,700. The requests continued to arrive at the agency after the armistice in November 1918. By the middle of 1920, the number of policies issued topped 4.5 million and the total value of the coverage exceeded $40 billion. In short order, the U.S. government became the world’s largest supplier of insurance.

The government did not retain this title for long, however. The bureau’s annual report for 1920 urged that “every effort should be made to bring home to our soldiers, sailors, and marines the importance of continuing their insurance.” But returning Veterans were not receptive to this messaging. Most let their policies lapse rather than convert them into one of the long-term U.S. Government Life Insurance policies the bureau began offering in 1919. While the private insurance industry experienced a boom in sales in the post-war period, fewer than 650,000 Veterans or personnel still on active duty invested in a government plan and they carried on average less than $5,000 in coverage. Despite the disappointing aftermath, the War Risk insurance program introduced in 1917 was considered enough of a success for Congress to authorize a new version, called National Service Life Insurance, on the eve of World War II. After a slow start, almost all of the more than 16 million Americans who served in the war would enroll in this insurance program.

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 93: Occupational Therapy Floor Loom

During World War I and afterwards, the United States committed to rehabilitating sick and wounded soldiers so they could resume productive lives in the civilian workforce. The emerging field of occupational therapy played a crucial role in the rehabilitative process.