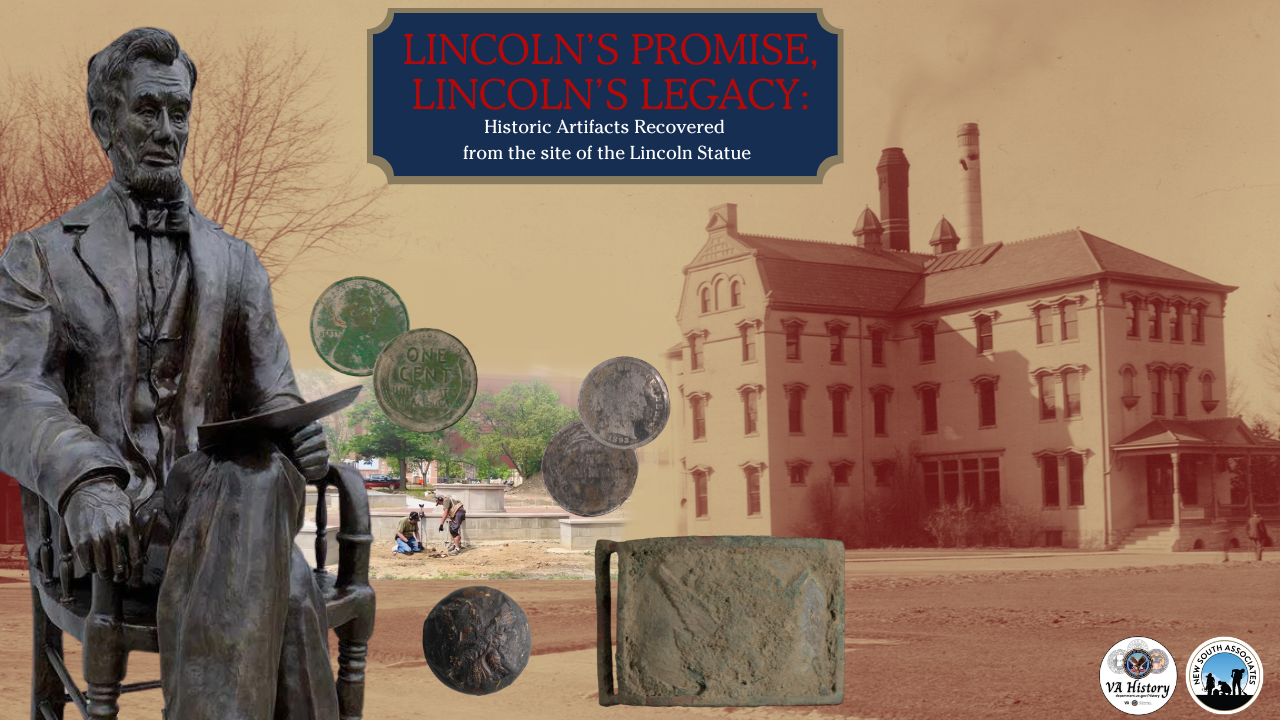

It all started when Bill DeFries, President of the American Veteran’s Heritage Center (AVHC), lost his wedding ring at the construction site for the statue of Abraham Lincoln on the campus of the Dayton VA Medical Center. He requested the assistance of the Dayton Diggers, a local nonprofit whose mission is to “research, recover, and document history” through their use of metal detector survey. The machines used by Dayton Diggers emit an electromagnetic field that responds to metal objects hidden below the ground surface. When they pinpoint a target, they use minimally invasive excavation to remove the object from the soil. In addition to the misplaced wedding band, their team uncovered historic artifacts that can be used to understand the history of Veteran care in Dayton.

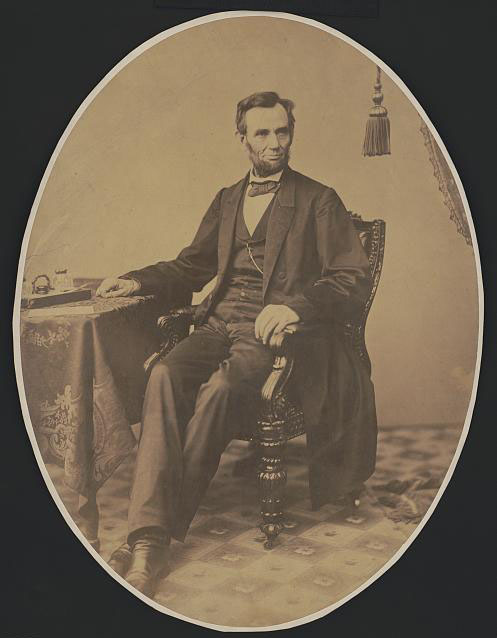

In 2018, the American Veteran’s Heritage Center formed a committee in collaboration with the Lincoln Society of Dayton raise support for a project to erect a bronze statue of our 16th President on the Dayton VA campus. They commissioned Ohio sculptor Mike Major to create the monumental piece of artwork that will be unveiled and dedicated on the historic campus on Monday, September 16. In 1867, this site was chosen for the Central Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, one of the federal agencies who would become the Veterans Administration in 1930. For more than 150 years, Veterans of all walks of life have come here to make lives for themselves, to receive state-of-the-art medical care, and when the time comes, for their final resting place.

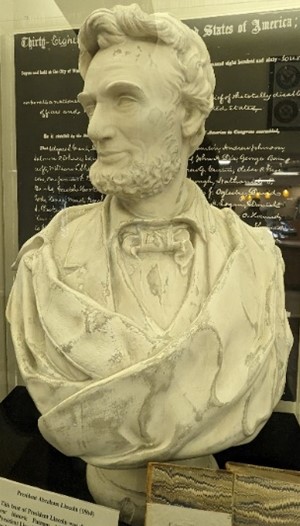

While this statue is the latest representation of the Great Emancipator to make its home here in Dayton, it is far from the first. As early as 1875, a plaster bust of Abraham Lincoln held a place of honor inside the original Putnam Library, back when it was still located in the Old Headquarters. Nowadays, this plaster bust lives in the lobby of the Dayton VA Medical Center.

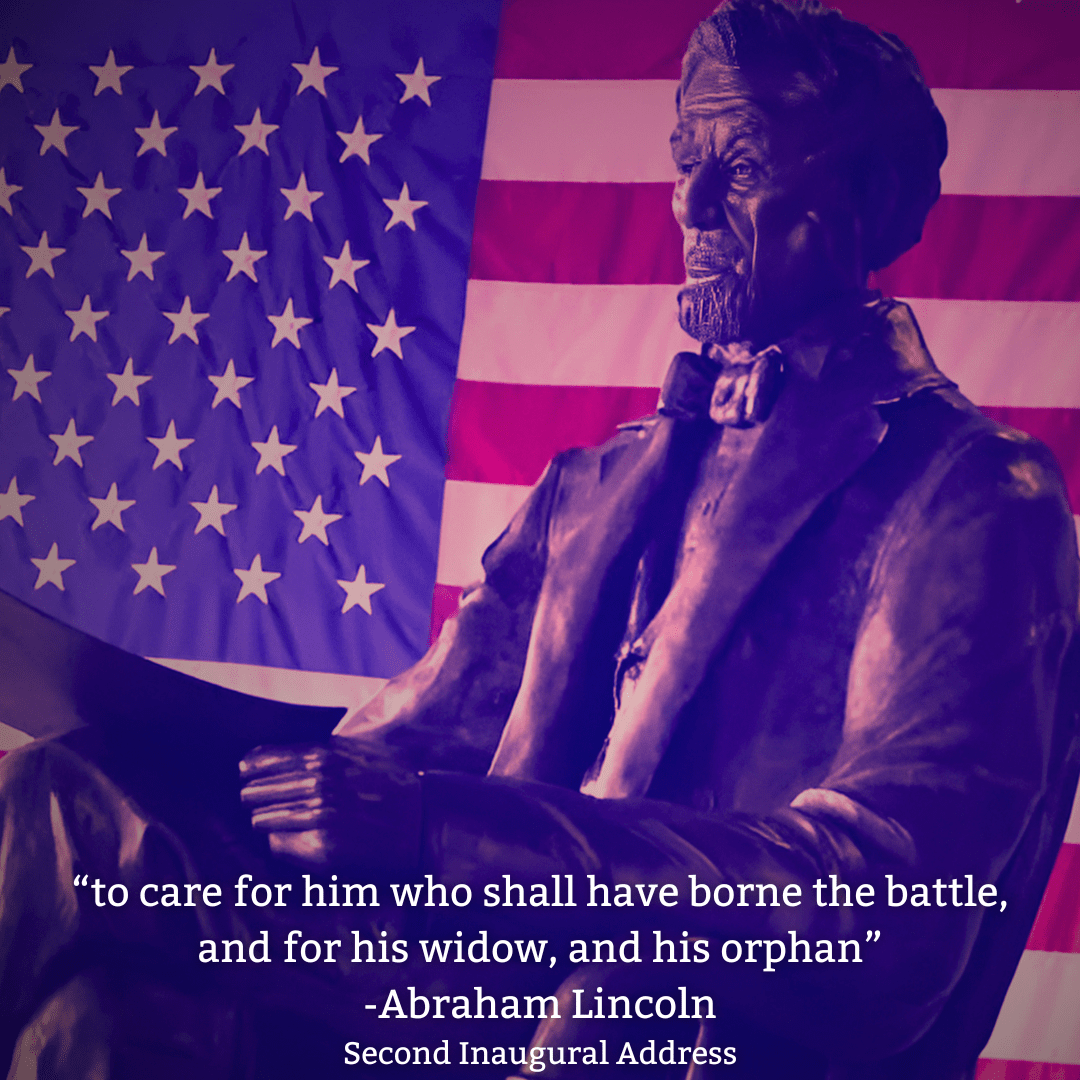

President Lincoln has been memorialized countless times for many reasons, but here at the VA, he is recognized as the president responsible for signing the bill that established the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. On March 4, 1865, he authorized the federal agency responsible for housing and caring for Veterans of the Civil War. From just three homes located in Maine, Wisconsin, and Dayton, a network of 11 residential communities dedicated to the care of Veterans sprang up between 1865 and 1930. With the establishment of the Veterans Administration in 1930, the National Homes became formally part of the agency we know today as the Department of Veterans Affairs. Just a day after signing this legislation, President Lincoln would deliver his second Inaugural Address, which includes the words that would serve as inspiration for the VA’s motto and mission statement:

“With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

It is this reason that the American Veterans Heritage Center and the Lincoln Society of Dayton have raised the support to bring a new statue of Lincoln to the Dayton VA. Several months of construction were needed to prepare the site for the statue, and it is during that construction that Bill misplaced his wedding band. Through the assistance of Dayton Diggers, the wedding band was found in addition to several other artifacts lost to time.

The artifacts were discovered outside of Putnam Library. This building was first built in 1890 as the Quartermaster’s Building. Shortly thereafter, it became the new home of the growing collection of books donated by Mary Lowell Putnam. Most of objects recovered from the metal detector survey represent recent disposals. These items include coins, ammunition casings, pop tabs, and soda caps from the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The most historically significant finds can be reliably dated to the National Home period (a span of about 65 years); these include coins, a uniform coat button, and a belt plate.

The two coins that can be dated to the National Home period include a 1893 Barber Dime and a 1911 Lincoln Penny. This style of dime was designed by Charles Barber and was minted in Philadelphia between 1892 and 1916. These dimes faced mixed reactions from the public, some found the depiction of Liberty on its face to be beautiful, but others found it grotesque. Perhaps this coin was dropped behind the library by a group of Veteran soldiers who had been passing it around during a spirited debate about its design. The Lincoln “Wheat Penny” was designed by Victor Brenner to commemorate Lincolns 100th birthday and was minted in three cities between 1909 and 1959, when the obverse image that gave this coin its nickname was replaced by a depiction of the Lincoln Monument. The specific coin recovered from the Lincoln site was minted in Philadelphia in 1911 and could have been dropped behind Putnam at any point in the 113 years since its creation.

The next artifact is easily identified as a uniform button, most likely from the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. This style of button was standard on the Union army-inspired uniforms worn by all residents of the home. These brass buttons were embossed with an eagle, typically surrounded by the letters NHDVS. There are several examples of this kind of button in the Permanent Collection of the National VA History Center; these kinds of artifacts help us understand more about the uniforms the men of the National Home wore.

The final object recovered from the site of the Lincoln statue is a Union Army belt plate. When it was new, these brass plates featured the image of an eagle with its wings outstretched and holding a banner that reads “E Pluribus Unum”, the de facto motto for the United States during the use-life of this object. While many of the design features are difficult to observe due to the objects condition, two wings and the body of an eagle are clearly visible. Closer inspection using state of the art digital imaging equipment revealed slightly more detail, including more of the eagles head and the scroll held in its beak. This design first appears in the Army’s uniform regulations in 1851, then again in ‘57, ‘61, and ‘63. It was initially designated for use with the belt and saber for infantry non-commissioned officers. Some evidence suggests that this model of plate became less popular as the war went on due to the decline in the use of the sword, but other indicators suggest it was worn nearly universally by the officer corps through the entire conflict. Regardless, it is likely this buckle was a prized memento of some old Veteran’s service and may have passed through several hands as an heirloom before ending up in the ground outside Putnam.

Whether in 1861, or in 1909, or even way off in 2024, Americans have sought to honor and memorialize the man credited as our greatest leader. The statue of Abraham Lincoln to be dedicated in Dayton in September 2024 represents the latest in a long line of monuments to the savior of the Union, and its construction provided a unique opportunity to engage with the material remains of the legacy he began.

By Gage Huey

Museum Collections Manager, National VA History Center

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

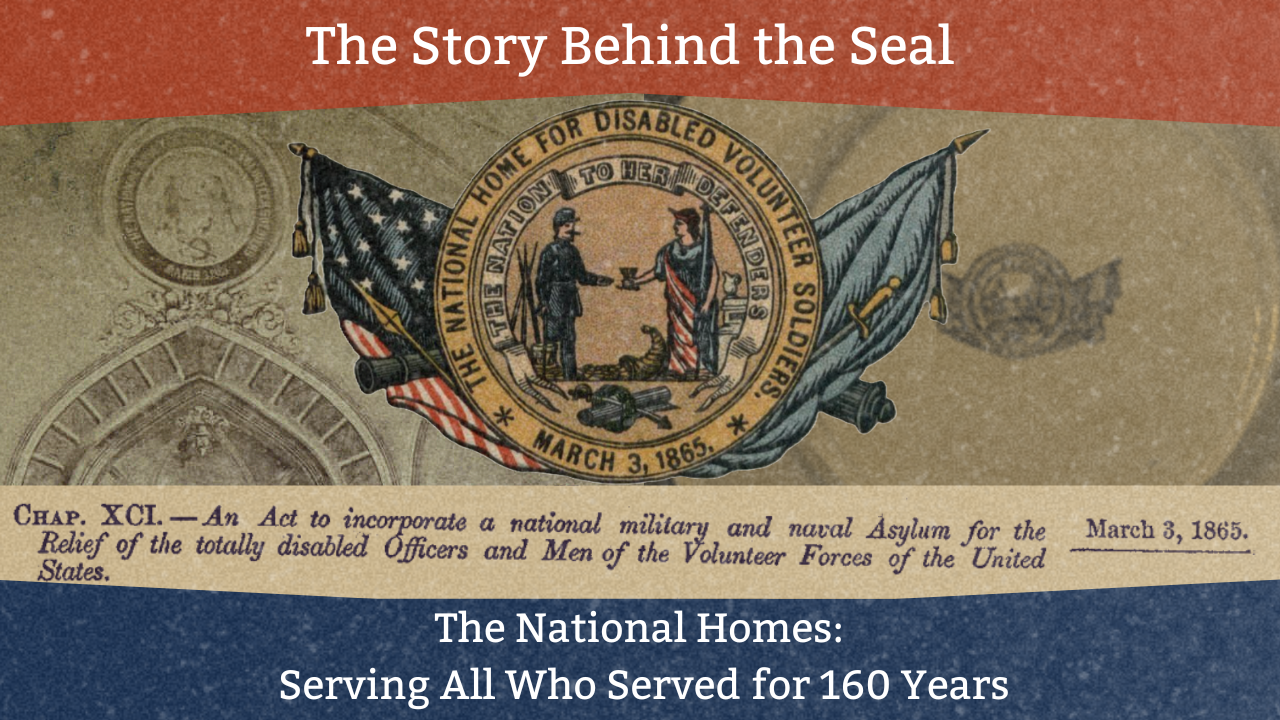

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? Fire Safety and Prevention at the National Homes

Fire safety may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about Veteran care, but during the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers period (1865-1930), it was a critical concern. With campuses largely constructed of wooden-frame buildings, housing thousands of often elderly and disabled Veterans, the risk of fire was ever-present. Leaders of the National Homes were keenly aware of this danger, as reflected in their efforts to establish early fire safety protocols.

Throughout the late 19th century, the National Homes developed fire departments that were often staffed by Veteran residents, and the Central Branch in Dayton even had a steam fire engine. Maps from this era, produced by the Sanborn Map Company for fire insurance purposes, reveal detailed records of fire prevention equipment and strategies used at the Homes. These records provide us with a rare glimpse into evolving fire safety measures in the late 19th and early 20th Century, all part of a collective effort to ensure the well-being of the many Veterans living there.