While fire safety may not come to mind when you think of the efforts made to care for our nation’s Veterans, fire prevention in the context of VA has a rich history. In fact, during the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers period (1865-1930), fire safety would have been one of the largest items of concern for the leadership, staff, and the thousands of Veterans who resided in the Homes. But to understand how this came to be, we must first understand the historic context the National Homes existed.

From October 8 – 10, 1871 the city of Chicago experienced one of the most catastrophic fires in American history. The impact of this fire and others like it has shaped the ways we practice safety to this day.

While many cities and states were commemorating Fire Prevention Day as early as 1911 (the 40th anniversary of the Chicago Fire), it was not until 1919 that the National Fire Protection Association, and its Canadian sister organization, began lobbying for an official day of recognition for fire safety and prevention. This led to a proclamation by President Woodrow Wilson of Fire Prevention Day in 1920, and eventually President Calvin Coolidge proclaimed the Sunday to Saturday period in which October 9 falls to be Fire Prevention Week in the United States.

Imagine what it must have been like to prepare a campus largely constructed of wooden-frame buildings meant to house hundreds of disabled, often elderly men for the possibility of fire. Now take those concerns and multiply across 11 different facilities, and you’ll be left with a pretty decent idea of how the Board of Managers of the National Homes must have felt.

Luckily, their preparations are recorded in documents that help the historians, archivists, and curators at the National VA History Center reconstruct the story of those who served our nation’s Veterans during this formative period. In the 1890 Annual Report of the Board of Managers, Central Branch Governor Col. Harris details his inspection of several of the buildings on campus and remarks on the need for fire safety.

He admits that prior to having seen them himself, he hadn’t realized how gravely the wooden barracks that housed the Veterans needed fire escapes. These sorts of design measures would have gone a long way to promote fire safety and preparation, and represent a very early step in the development of fire services in VA.

We know from Historic records and photographs that several of the National Homes maintained their own fire stations, staffed with civilian fireman and resident Veterans on work duty. At the Central Branch in Dayton, the earliest record of the Home Fire Department comes from J.C. Gobrecht’s 1875 Guide-Book to the Central Branch, in which he describes the “very handsome” steam fire engine that was named in honor of Louis B. Gunkel, the first Governor of the Central Branch, as well as the fire brigade itself.

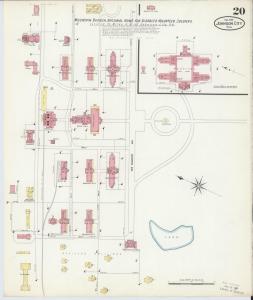

Our next line of evidence for fire preparation comes from an insurance company, of all places. Starting in the late 19th century and continuing until the 1970s, The Sanborn Map Company began producing lithographed city maps that were color coded and annotated to allow property owners and fire insurance companies to establish their liability to fire damage.

These maps often recorded the stock of equipment on hand to fight fires, and in many cases even shows where inside the building certain prevention tools were stored. This gives us an exclusive look into exactly how the National Homes were preparing for this very real threat. One of the other great benefits of these maps is that we can use them in tandem with other historic records to better understand the ways that fire prevention methods changed over time.

For example, we know that in 1880 there were no civilian firefighters employed at the home, and that the fire brigade would have been comprised of resident Veterans volunteering or assigned the task as part of their work duty. The first real numbers concerning the Veterans serving on the Home Fire Department aren’t published until the 1888 Annual Report, which tells us that just seven residents of the Home were working as firemen that year.

About a decade later, the 1897 edition of the Sanborn map shows us that the Home Fire Department was staffed by 50 men and one steam fire engine (likely the same engine described by Gobrecht), and that these men were equipped with six hose reels containing a total of 2,950 feet of hose, nearly the length of 10 football fields!

The brigade was also in possession of four hand extinguishers and a hook and ladder truck which equaled to 100-feet of ladder. In the case of Memorial Hall, the map details exactly the kinds of changes in fire prevention that the Home took in the years between the two maps being produced. The 1897 map shows that they have added additional spools of hose, in addition to the 50-foot hoses on the first floor and on the second-floor gallery that were present earlier in 1886. This version also contains 100-foot spools of hose directly connected to hydrants in the basement.

Some of the best evidence of fire prevention in the National Home Period comes from the Mountain Home Branch, located in Johnson City, Tennessee. While Sanborn maps for other branches are fragmentary or nonexistent, the entire Mountain Home campus was mapped and shows the types of preventative measure details that the branch took in the first decades of the 20th century. This resource proved invaluable as I began researching an object that speaks directly to the efforts of the National Homes to prevent fires, efforts that continued in full force with the creation of the modern VA in 1930.

This 100-foot linen fire hose comes from the Mountain Home Branch and was manufactured by Charles Niedner and Sons in the year 1959. It is folded and stored inside a painted iron rack. When researching the artifact, I quickly realized that it was not one hose, but two connected by brass couplings.

While we did not unravel the hose to obtain an exact measurement, the consensus from historic and contemporary resources is that 50 feet is a standard measurement for fire hoses that has been followed at least since the 1880s. With the two hoses linked together by their couplings, that gives us a hose measurement of 100 feet, exactly the length of hose described on the Sanborn Maps.

Additionally, the maps from Johnson City tell us that as early as 1908, “All main buildings have vert. pipes and supply with 1 ¾ inches hose each floor”, referring to the diameter of the brass coupling that connects the hose to the water supply. This means that the hose could have conceivably come from any of the buildings on campus; and while the hose was manufactured in 1959, it is likely that the rack it sits inside was around for several decades before.

Interestingly, the measurement of the hose coupling in our collection is actually a little smaller- with a diameter of only 1 1/2 inches. I wondered why this was and assumed that at some point in between 1920 (the last map that we have from Mountain Home) and 1959, the regulations for the size of hose couplings must have changed. After spending an afternoon staring at the fire insurance maps, I left my lab and came face-to-face with a piece of equipment that held the answer to this question.

An unassuming vertical pipe capped with a brass coupling has been on the third floor Building 126 since 1933, the year the building was constructed and presumably, the year the coupling was created (the brass is stamped with the year of manufacture). I have walked past this pipe dozens of times without giving it any thought at all, until I realized that this was the very same kind of installation described on the Sanborn Maps.

Even on the earliest map, the abbreviation “V.P.” was present, followed by hose measurements. On later maps, the abbreviation was written out as “Vertical Pipe”, but I still didn’t quite understand what that meant. It wasn’t until I was observing the pipe coupling and saw the measurement “1 1/2” stamped in the brass that I realized that these were the very same kinds of pipe that would have accompanied the hose in our collection.

While we do not know exactly when the shift from 1 3/4 inch couplings to the 1 1/2 inch couplings that we see in the 1959 hose, the fact that the vertical pipe from 1933 has the later measurement tells us that this shift likely began in the 1930s, possibly in tandem with the transition of the National Homes into the modern VA.

As is so often the case here at the VA History Office, the past and the present are not nearly quite so distant as it may seem. The fire hose and vertical pipe stand as testaments to the evolving nature of fire prevention as a fundamental part of Veterans care. While these artifacts may date outside of the timeframe of the National Home Period, their place in the historic context of fire management shows us that practices that began during the early decades of the century continued for much longer, just as the facilities that were originally the National Homes continued providing life-changing care for Veterans through the years.

By Gage Huey

Museum Collections Manager, National VA History Center

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.

Curator Corner

Lincoln’s Promise, Lincoln’s Legacy: Historic Artifacts Recovered from Site of Dayton Statue

It all started when Bill DeFries, President of the American Veteran’s Heritage Center (AVHC), lost his wedding ring at the construction site for the statue of Abraham Lincoln on the campus of the Dayton VA Medical Center. He requested the assistance of the Dayton Diggers, a local nonprofit whose mission is to “research, recover, and document history” through their use of metal detector survey. The machines used by Dayton Diggers emit an electromagnetic field that responds to metal objects hidden below the ground surface. When they pinpoint a target, they use minimally invasive excavation to remove the object from the soil. In addition to the misplaced wedding band, their team uncovered historic artifacts that can be used to understand the history of Veteran care here in Dayton.

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? 2nd Lt. George Fair’s 140 Year Journey

It started with a medal. Later on a button. Then, walks along the trails at the Dayton VA Medical Center and to the National Cemetery. Finally, it ended at a tall monument at the intersection of Monument Avenue and Main Street in downtown Dayton.

Well, it didn't quite end there. This was just the beginning in learning about the soldier, whose likeness sits atop the Montgomery County Soldier's Monument and stands watch at the main entrance to the Dayton VA Medical Center.

This is the story of a curator diving into the story of George Fair, Dayton's Veteran model and a 140 year journey.