A blue circle with a golden phoenix rising from the ashes. This was the shoulder patch worn by the more than 1,000 physicians, dentists, and other medical professionals serving in the U.S. Army who were assigned to Veterans Administration hospitals during World War II.

In 1940, with war already raging in Europe and Asia, VA began preparing for potential American involvement in the conflict. VA Administrator Frank T. Hines informed Congress that the agency was coordinating with the War Department to assist in the event of a national emergency with both hospital bed space and highly trained medical staff.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into World War II, the U.S. Army’s need for physicians and other healthcare professionals was acute. As the Surgeon General of the Army, Maj. Gen. Norman T. Kirk, bluntly reported, “It was difficult during the past year to secure the additional Medical Corps officers needed to meet the requirements of the increasing Army since there are not sufficient physicians available to meet both military and civilian medical needs.”

The military’s demand for healthcare professionals drained staff from the civilian medical community and VA alike. Between 1942 and mid-1944, 16 percent of VA employees were furloughed for military service. Draft deferments were possible for those supporting national health but were rare. Well into the war, only 23 deferments for VA employees had been issued by civilian authorities.

The loss of so many skilled medical workers created its own set of problems for VA, especially as the war progressed and newly discharged Veterans with injuries filled up VA hospital beds. A December 1943 agreement between Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and VA’s Administrator paved the way for a collaborative use of limited medical personnel. Their solution included inducting select VA doctors and dentists into the Army but allowing them to remain at VA facilities.

Surgeon General Kirk reported that “984 physicians who were on duty with the Veterans Administration were commissioned in the Medical Corps of the Army in grades commensurate with their former civil service ratings and placed on duty with that organization.” By December 1944, the Army listed 1,622 Medical Corps and 149 Dental Corps officers assigned to VA.

In addition to physicians and dentists, demand was also high for nurses, orderlies, and related positions. However, by the later stages of the war, VA had creatively adjusted to these personnel shortages. To fill nursing vacancies, hospitals were authorized to recruit locally, using a variety of sources including nursing assistants and volunteer nurse aides. Hospitals also utilized detachments of enlisted men assigned to limited service, conscientious objectors, and even prisoners of war as hospital attendants.

While detailed to VA, Army personnel wore a distinctive shoulder sleeve insignia designed by the Heraldic Section of the Army’s Office of the Quartermaster General. The phoenix emerging from the flames was meant to represent “the restoration of the veteran as a new and vigorous citizen free to engage in his useful pursuits.” The patch was approved by the chief of the Heraldic Section on June 30, 1944.

The most notable soldier to affix the VA patch to his uniform was Gen. Omar N. Bradley. The four-star general commanded the 12th Army Group during the race across France and the drive into Germany in 1944-45. After Germany surrendered, President Harry S. Truman appointed Bradley to serve as the head of VA on August 15, 1945. Bradley proudly wore the shoulder insignia throughout his time at VA, as seen in various photo portraits in both his summer and winter uniforms.

The rapid demobilization of the U.S. armed forces following Japan’s surrender in September 1945 created an unprecedented demand for VA benefits and medical services. But the return of millions of Americans to the civilian workforce also presented a solution to VA’s staffing challenges.

VA launched a massive hiring effort after the war, increasing its staff size from 64,639 in July 1945 to 168,603 in July 1946. The new hires included over 1,000 doctors, raising the total number of physicians and dentists employed at VA from 2,700 to 4,000. Fewer than 400 were on active duty in the military. At the same time, by mid-1946, the agency replaced most of the enlisted soldiers loaned to VA and other temporary workers with regular full-time employees.

General Bradley departed VA a little over a year later. He relinquished his position as VA Administrator to become the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army in November 1947.

By Michael Visconage

Chief Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 90: Pearl Harbor Unknowns Marker

Seamen 1st Class Raymond Emory survived the attack on Pearl Harbor. Decades later, his research and advocacy led the government to add ship names to the markers of the Pearl Harbor unknowns interred in the National Cemetery of the Pacific.

History of VA in 100 Objects

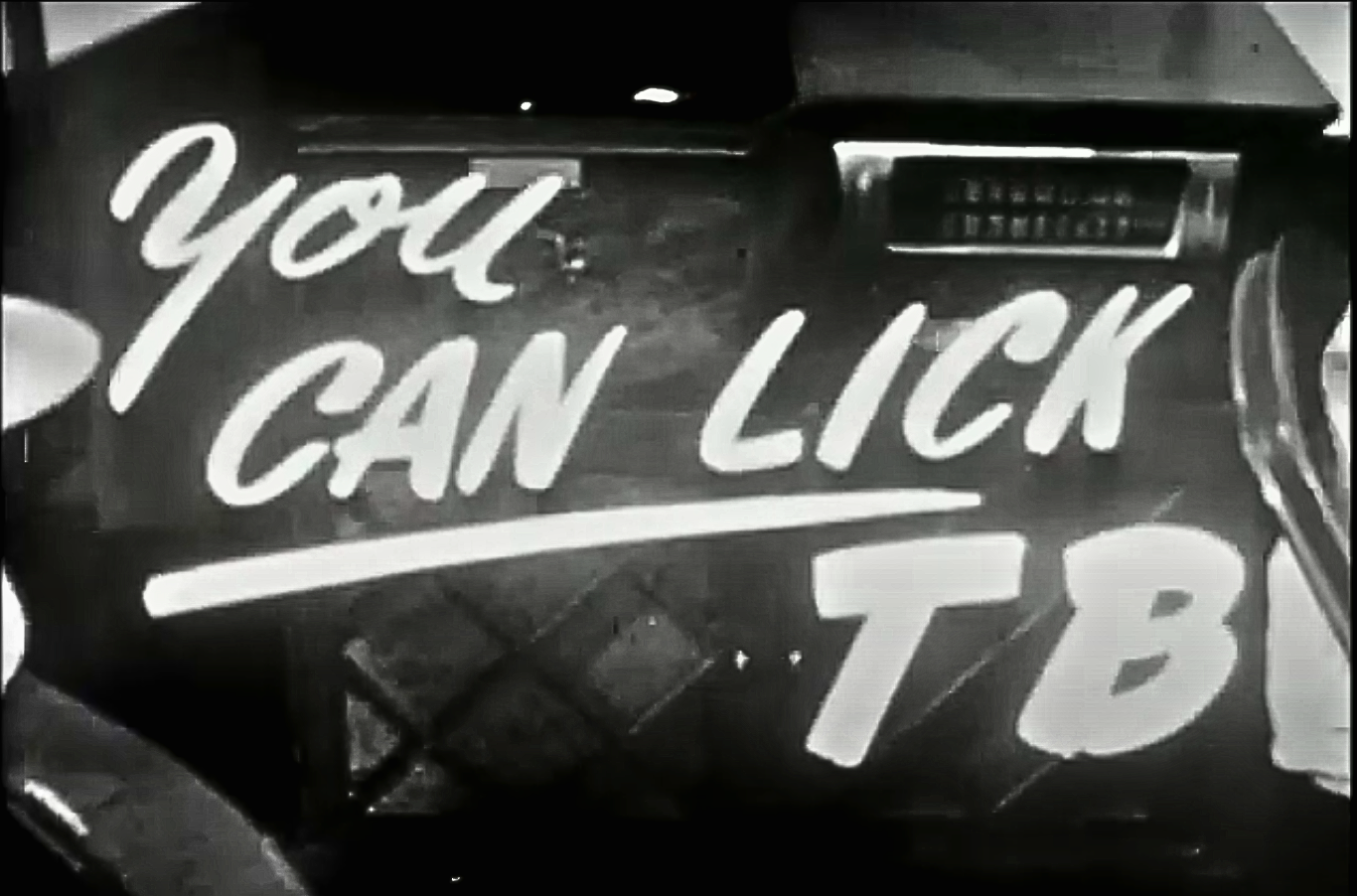

Object 89: VA Film “You Can Lick TB” (1949)

In 1949, VA produced a 19-minute film titled “You Can Lick TB.” The film follows a fictional conversation between a bedridden Veteran with tuberculosis and his VA doctor, dramatizing through brief vignettes the different stages of TB treatment and recovery.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 88: Civil War Nurses

During the Civil War, thousands of women served as nurses for the Union Army. Most had no prior medical training, but they volunteered out of a desire to support family members and other loved ones fighting in the war. Female nurses cared for soldiers in city infirmaries, on hospital ships, and even on the battlefield, enduring hardships and sometimes putting their own lives in danger to minister to the injured.

Despite the invaluable service they rendered, Union nurses received no federal benefits after the war. Women-led organizations such as the Woman’s Relief Corps spearheaded efforts to compensate former nurses for their service. In 1892, Congress finally acceded to their demands.