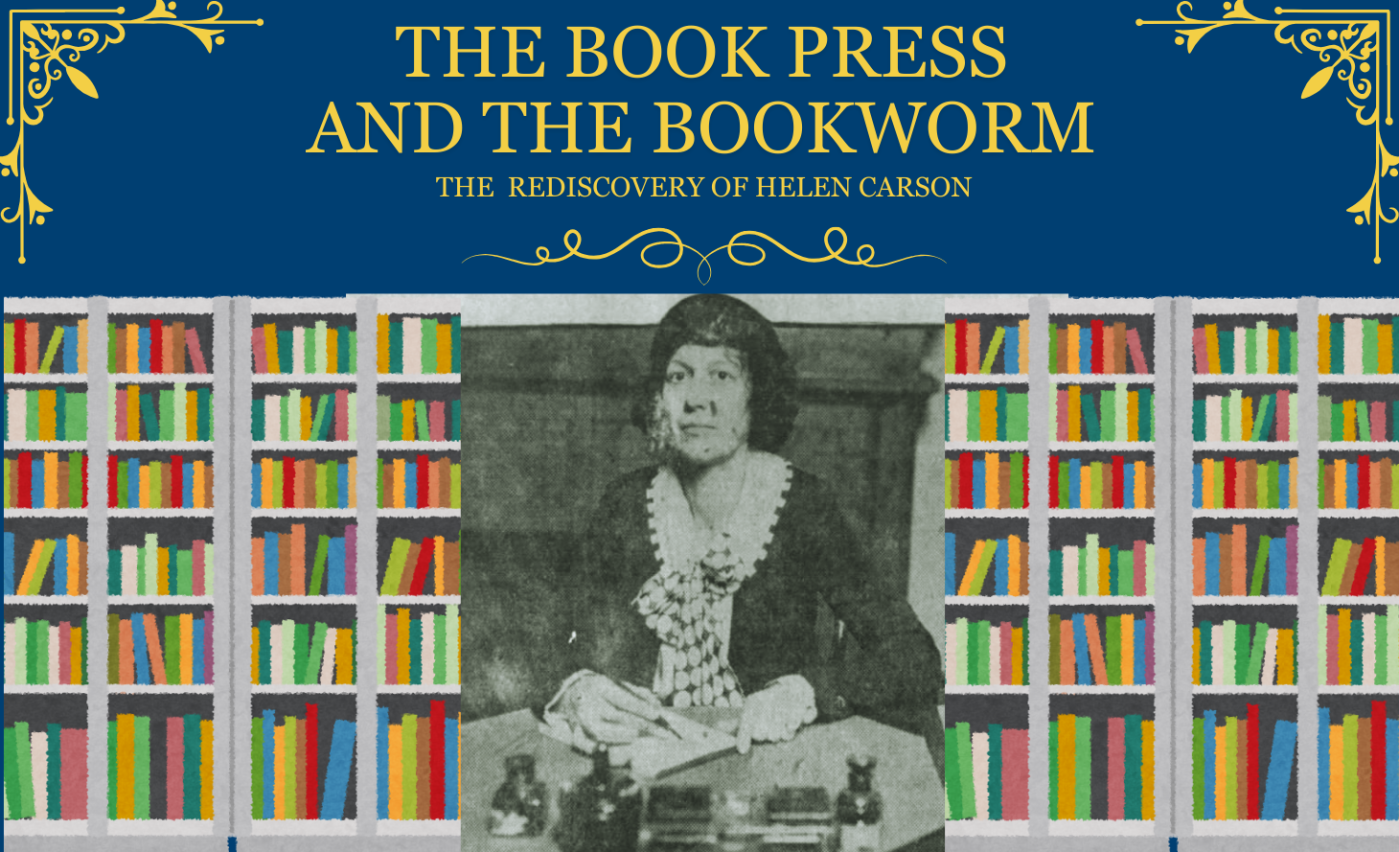

The Book Press and the Bookworm: The Rediscovery of Helen Carson

In the United States, April is a big month for Libraries. National Library Week is annually celebrated this month, and April 16th is dedicated as National Librarian Day. Last month, our Senior Archivist Robyn re-introduced the world to Mary Lowell Putnam, the author and benefactress whose donations kick-started the library at the Central Branch of the National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Dayton. Now that you are familiar with the woman who started this collection, let me tell you the tale of the woman who brought Mary’s collection into the 20th century and would one day become the first Chief Librarian in the History of VA.

It isn’t often that researchers who work with historic objects get to know the people who used those objects every day. Sometimes we get lucky and can link artifacts to certain facilities or buildings on a historic VA campus, but usually we must look for more hidden lines of evidence to figure out how an object fits into the history of those who care for our Nation’s Veterans.

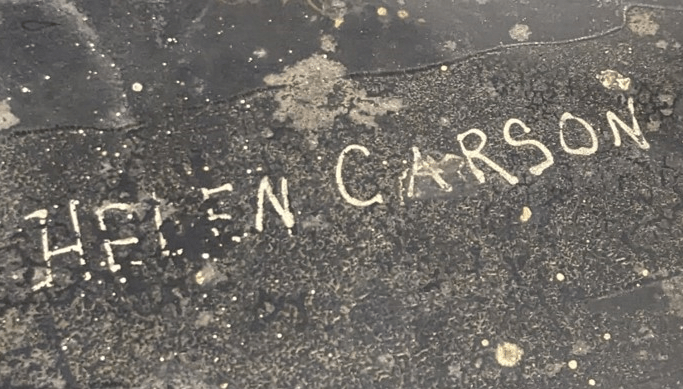

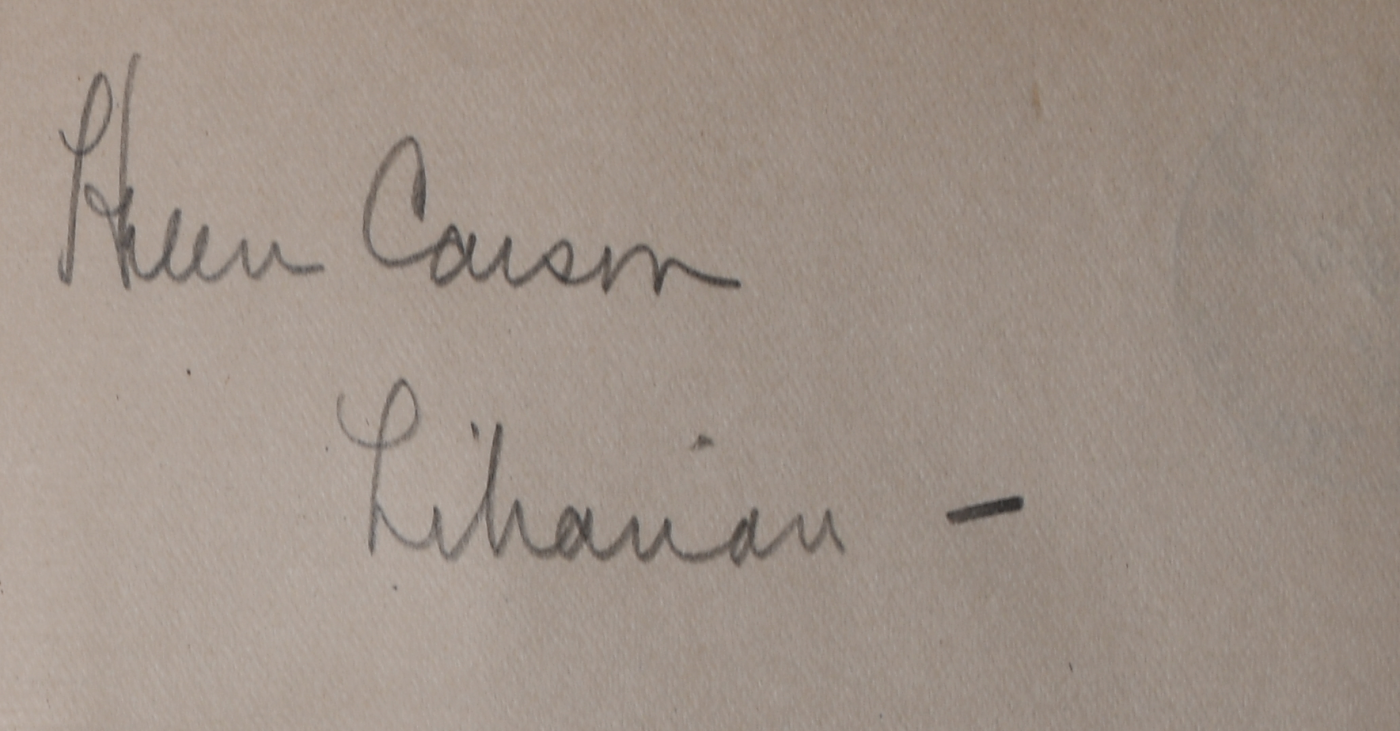

As nice as it would be, it isn’t as if many artifacts turn up labeled with their owners’ names! So, imagine my surprise when my teammates and I began sweeping Putnam Library for any historic objects left behind before the building was closed for renovation, and found just that, a book press.

As far as artifacts go, its story seemed simple: book presses like these would have been used to help maintain and repair the thousands of books read in Putnam Library since it opened in 1879. The day that I first got up close and personal with the press, I noticed a woman’s name scraped into the black paint of the platen (the technical name for the big metal plate used to hold books together). It said “Helen Carson” in big, legible letters. As we carefully transported the heavy press down the many stairs inside Putnam Library, I looked at the name and thought “Hmm…wonder who that is?”

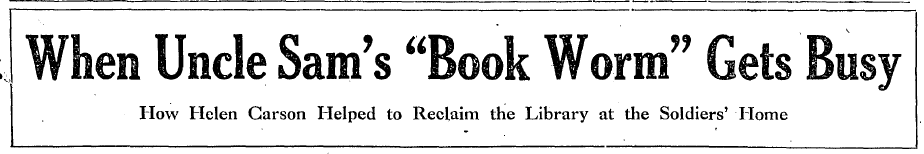

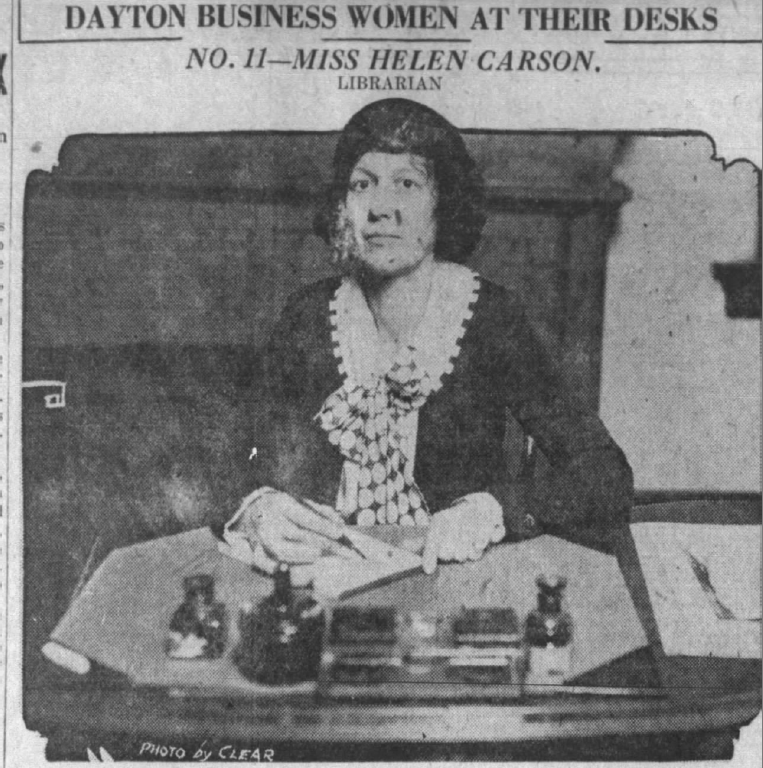

It wasn’t for several more weeks that I read her name again, but this time it was in a very different place. I was doing some research on the busts that once watched over the patrons of Putnam Library and was reading through historic newspaper articles available to me thanks to my public library card. Among the dozens of results, the headline of a full-page article from the Dayton Daily News practically shouted at me from the screen.

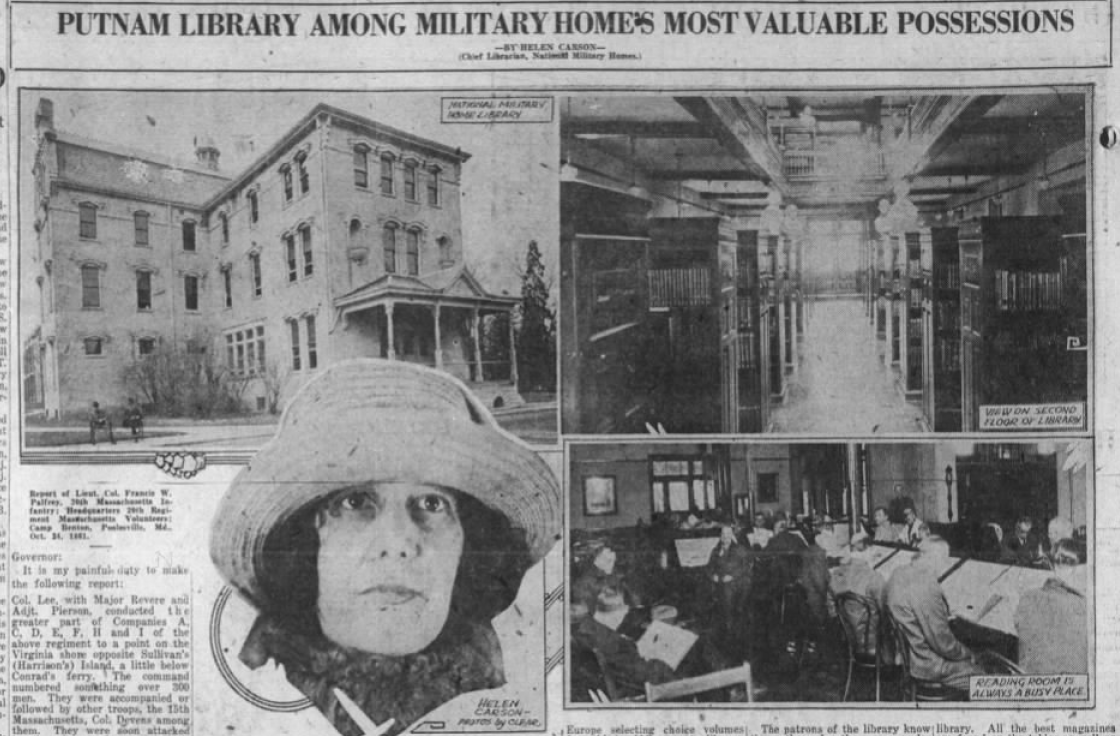

As soon as I saw her name, I ran downstairs to where the National VA History Center houses our collections. I thought the name sounded familiar but needed to see it for myself. Sure enough, it was a match! The article tells the story of how Helen Carson, as the “Supervising Librarian of Military Home Libraries” helped modernize the Putnam Library. When Helen first arrived at the Central Branch in November of 1921, she found the Putnam Library in a bit of a mess.

After half a century of use by the countless Veterans living at the Home, the large collection of books had become, in the words of the Dayton Daily News, “considerably jumbled”. According to records, the Central Branch regularly employed Veterans in the Putnam Library, including a staff of six in 1919. Even so, the Dayton Soldier’s Home hadn’t had a regular, full-time librarian in many years. This must have been a source of frustration for the Veterans living here at the time, who would have needed to search among the collection for hours just to find a single book.

This all changed when Miss Helen Carson came to town; she set up a modern cataloging and classification system for the library and set to work reorganizing the bookcases. This was clearly done with a deep care for both her profession and the wellbeing of the Veterans.

Take, for instance the fact that when reorganizing the shelves and bookcases, she only used the upper shelves. She explained to the reporter for the newspaper that this allowed Veterans to look over the books on the shelf without needing to stoop over, something that the elderly and disabled members of the National Home greatly appreciated. Not just stopping at the books, Helen also set out to modernize the lighting system in Putnam Library, replacing old style globes that gave off very little light.

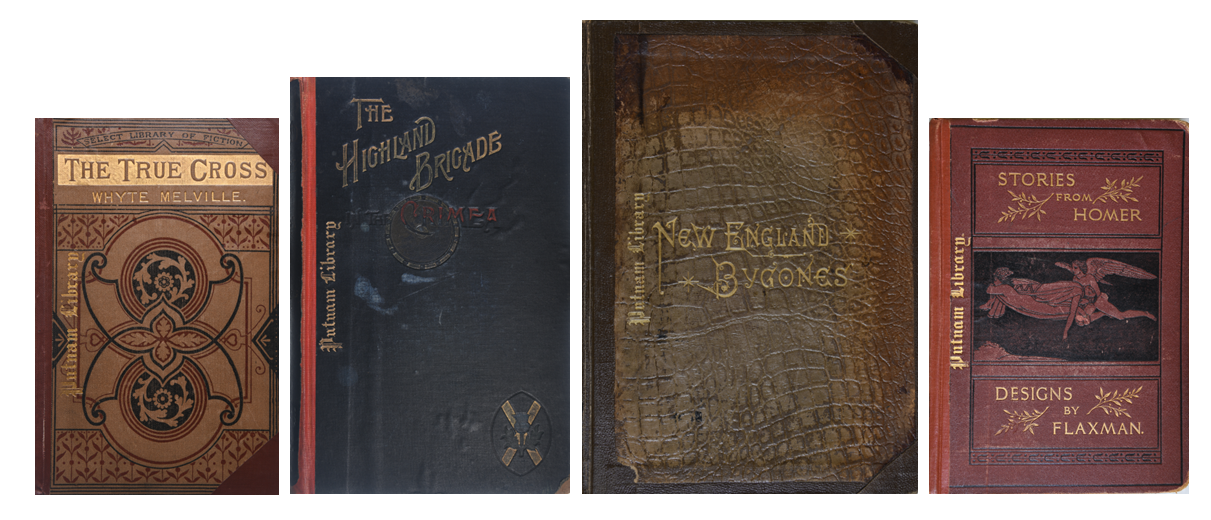

She saw that the Home Board approve her request for a modern lighting system, ensuring that Veterans coming into the library could easily find a book and read to their heart’s content. It is very likely that these “conveniently arranged droplights” are the very same light fixtures that hang in the library today. The article continues to sing Helen’s praises, explaining how she saw the bookcases scrubbed and re-varnished, and even that “each and every book was given attention, and bindings strengthened where necessary”.

This article is what I like to call a “Historic Home Run”: it directly links a person in history to a significant event and provides direct evidence of the kinds of tools and equipment (in other words, artifacts) that they would have used. We already knew that Helen was associated with this book press, because her name was inscribed on it. What we didn’t know is that behind that name was a 42-year career that took her from her hometown of Kansas City, Missouri all over the country in service of Veterans.

So, who was Helen Carson? In the 1922 write up in the Dayton Daily News, she is described as “a charming little lady whose love of the historical goes hand in hand with her love for books and pictures” (she’d fit in perfectly here at the History Center!). It was reported that her friends “number everyone who has met her or come to know her.” Her peers celebrated when she came to town and missed her when she left.

In addition to her social skills, she was quite gifted in the management and maintenance of library collections. It is unclear where she went to school, but census records indicate that she completed three years of education. Once she began working as a librarian on the campus of the Western Branch of the National Homes, she worked her way up and stayed employed at VA until her retirement in 1952.

She first appears in the papers in 1909 as a guest visiting the National Home located in Leavenworth, Kansas. By 1910 she became the librarian at the Hancock Library, where she worked for nearly a decade. Outside of work, she was hosting and attending bridge parties, progressive dinners, and other social events held at the National Homes.

In 1917, she even helped throw a “War Dance” to raise money for the American Red Cross. Later that year, she was registering women of the Home for the Women’s National Defense League. This was a national organization in which women could register for service to their communities to help the home front during World War I. According to The Leavenworth Times, Helen “showed considerable enthusiasm in what she seemed to consider duty to our country.” Helen continued to do her part to support the war effort in planting a “Liberty Garden” behind the library and helping raise $1,500 (equal to more than $30,000 today) for the United War Work Fund.

After the war, Helen began traveling from the Western Branch to the other National Homes to improve their library collections. In August of 1919 she traveled to Milwaukee, where she cataloged the Wadsworth Library at the Northwestern Branch. She returned to Leavenworth in December of that year.

In February of 1920, during the “4th Wave” of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, she caught a bad case of the flu. Sometimes we have so much more in common with figures of the past than we ever thought. Those of us who remember what it was like to work and live during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic may feel a connection with Miss Carson. She too, understood what it was like to live in interesting and uncertain times.

More than a year after her recovery, she traveled to the Southern Branch in Hampton, Virginia to help arrange the collection there. She stayed at Hampton for several months before moving on to Dayton, Ohio where her efforts were immortalized in the “Uncle Sam’s Bookworm” article. In the spring of 1922, an “unofficial report” was published in The Leavenworth Times that she had been appointed Inspector of Libraries for all the National Military Homes, with headquarters at the Central Branch.

This is confirmed in subsequent articles, including a report that names her as a member of the Board of Managers for the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. This role required her to travel to all ten of the National Homes and direct the organization and maintenance of their library collections. While the papers give Miss Carson several different titles including “Supervising Librarian” and “Inspector of Libraries,” she is identified as early as September of 1922 as “Chief Librarian,” the title that she would continue to hold for the remainder of her career.

For the next eight years, she would continue traveling the country, using her expertise to improve the quality of libraries at the Soldiers Homes, no doubt making friends and connections everywhere she went. During this time, she published some of her own writing in the Dayton Daily News, including a whole page write-up outlining the history of the National Homes and particularly, the Central Branch. She truly paved the way for all of us here at the National VA History Center, and it is so awesome to be able to give to her the same spotlight that she gave the historical figures she wrote about nearly a century ago.

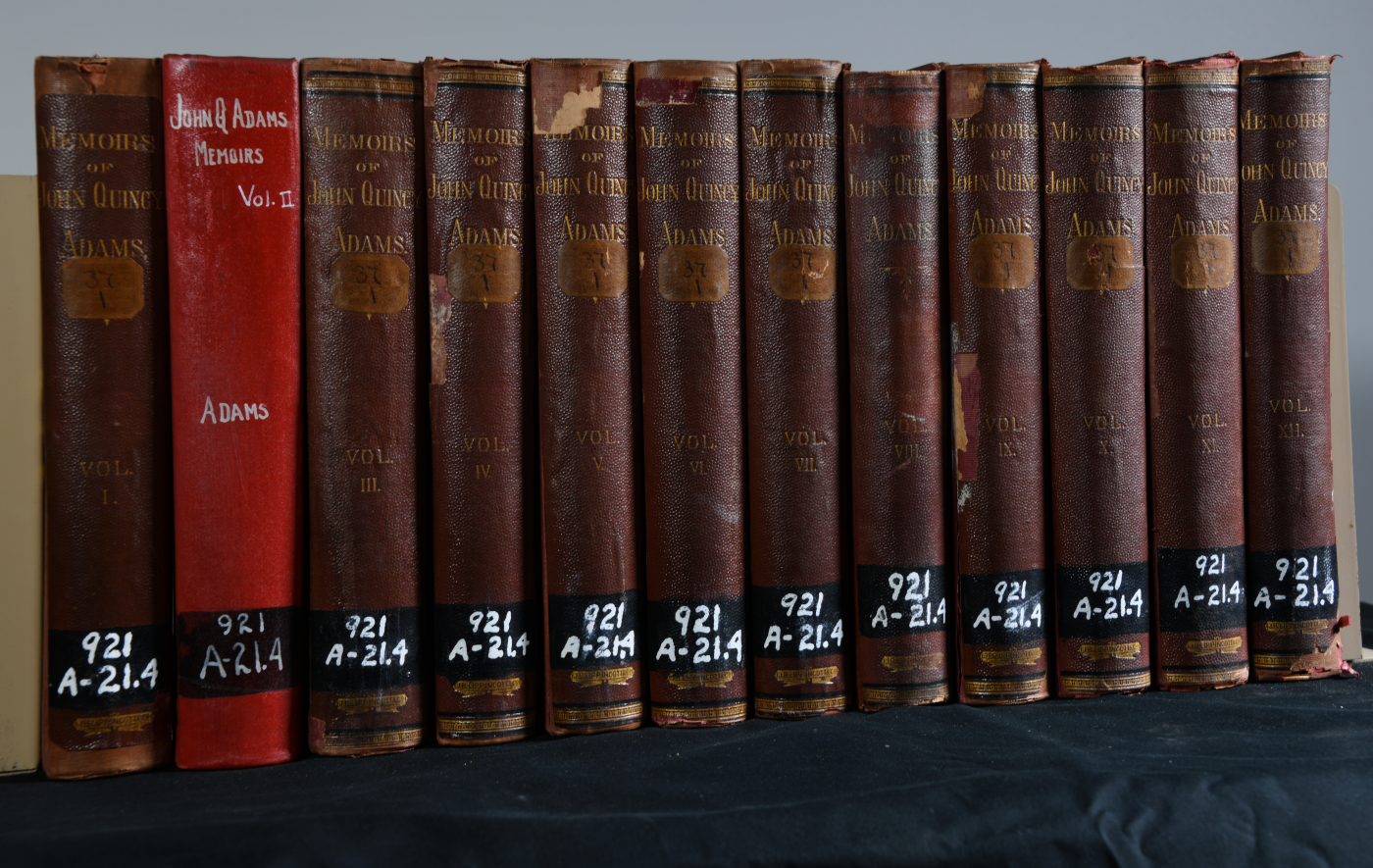

It is unclear exactly what roles Helen held as the National Homes transitioned into the Veterans Administration, as her inclusion in newspaper columns becomes scarce as time goes on. Nevertheless, she was just as dedicated to serving those who have served the nation. In 1952, she told The Journal Herald “You can’t discount the intelligence of your veterans”; a belief that she truly seemed to live by. Earlier in that article, she shares a tale of one such Veteran, who initially “wasn’t too interesting in reading. I started him on the Memoirs of John Quincy Adams”, but 12 volumes later, this old soldier was hooked.

At the time of her interview, she shares that the same Veteran now “takes 15 books a week from the cart that passes through the wards.” Many of the books cataloged by Helen, including the same memoirs she recommended to that Veteran have survived to present day. Nowadays, these books are part of the archival book collection managed by Deanna Ulvestad, one of my fellow team members at the History Center.

When interviewed about receiving an award for her many years of service, she put it plainly: “The Veterans Administration has given me the best years of my life.” We may never know the entire impact of her work on the Veterans she served, but the newspapers give us a window into how this woman’s remarkable career developed and flourished. This is sort of ironic, given that one of Helen’s first accomplishments here in Dayton was using newspaper archives to uncover the story behind Mary Lowell Putnam, another legendary female figure in VA History. Not to mention, Miss Carson did all that research without the conveniences of modern, digitized newspaper collections; she is truly an icon.

Just as she rediscovered the contribution of “Lady Putnam” to the Soldier’s Home in the 1920s, the life and career of “Miss Carson” has now been unearthed more than a century from her first visit to Dayton. Her work impacted the lives of countless Veterans, and her legacy shines as testament to public service. Like the many librarians who have come before and since, Helen Carson is a great American hero, and it is an honor to bring her story into the 21st Century.

Happy National Librarian Day from the NVAHC.

By Gage Huey

Museum Collections Manager, National VA History Center

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

Bringing them Home: America’s WWII Burial Program

VA History is defined by public service to those who have fought for this country. For nearly 250 years, Americans have responded to the challenges Veterans face in innovative ways. But what happens for those who do not return home? This is the story of three Americans who paid the ultimate sacrifice fighting fascism in Europe, how each one was honored after death, and how the VA History Office is preserving their story.

Curator Corner

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.