President Abraham Lincoln is one of the most revered figures in American history. Rankings of U.S. presidents routinely place him at or near the top of the list. Lincoln is also held in high esteem at VA. His stirring call during his second inaugural address in 1865 to “care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan” embodies the nation’s promise to all who wear the uniform, a promise VA and its predecessor administrations have kept ever since the Civil War.

Lincoln’s second inaugural address is inscribed on the north interior wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Directly across from it, engraved on the south interior wall, is another speech by Lincoln which is even more famous. It is arguably the greatest piece of oratory in the nation’s history. The speech, of course, is the Gettysburg Address.

Lincoln delivered the speech on November 19, 1863, at the dedication of the Soldier’s National Cemetery near the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Over 3,000 Union soldiers died at Gettysburg during the pitched three-day battle on July 1-3 that ended in Confederate defeat. Many of the dead were buried in makeshift graves. Wanting to give the Union dead a proper burial, a committee led by Gettysburg lawyer David Wills in October 1863 purchased a plot of land on the battlefield to serve as a cemetery. Reinternment of the fallen soldiers began later that month.

Wills invited Lincoln to attend the dedication and, in his capacity “as Chief Executive of the Nation, formally set apart these grounds to their Sacred use by a few appropriate remarks.”

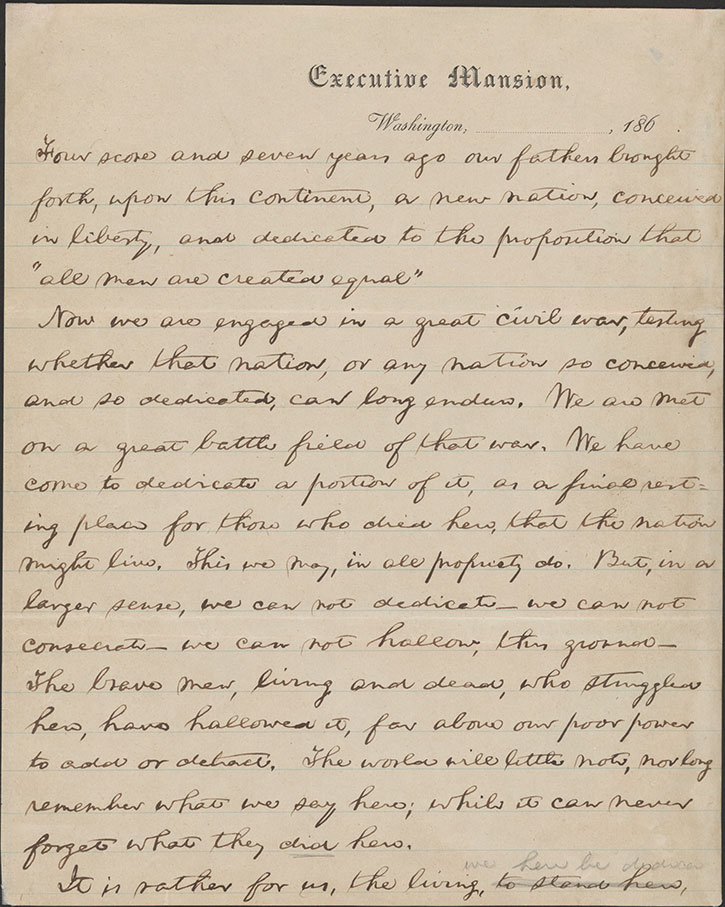

Per Wills’ instructions, Lincoln kept his remarks short and spoke for only a few minutes. But in a mere 272 words, beginning with the famous phrase “Four score and seven years ago,” Lincoln encapsulated the meaning of the war and its connection to the nation’s founding ideals. He ended the Gettysburg Address by urging his fellow Americans to honor the soldiers’ sacrifice and stay resolute to the cause, “that the nation, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

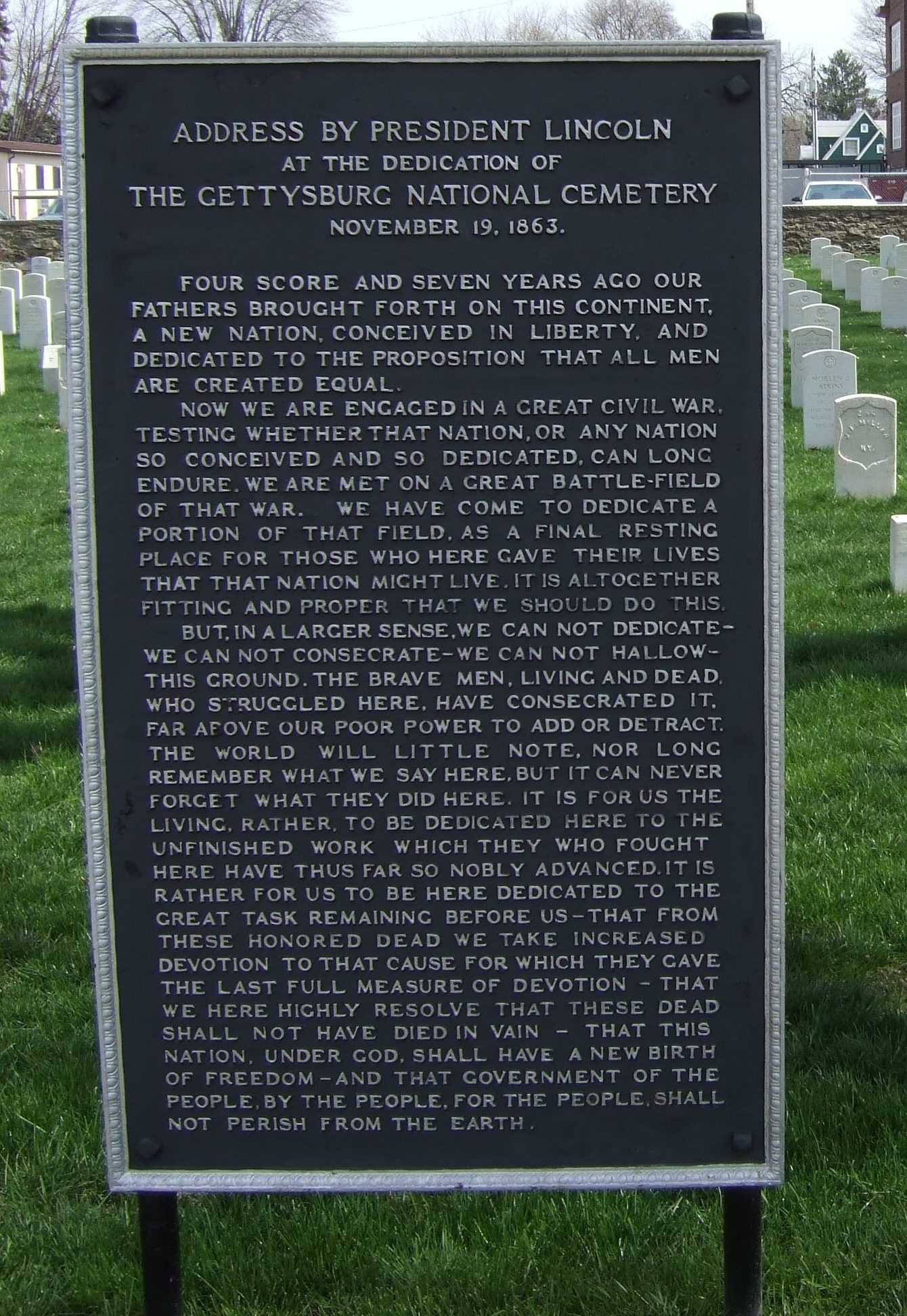

Ever since Lincoln first uttered those memorable words in November 1863, the Gettysburg Address has been linked to our national cemeteries. Efforts to incorporate the address as a permanent element of the cemetery landscape began in 1895 when Congress allocated money to create a monument to Lincoln’s speech at the cemetery in Gettysburg. Due to delays, the monument was not completed until 1912. In the meantime, in 1908, Congress approved a plan to produce a standard Gettysburg Address tablet to be installed in all national cemeteries in time for the centennial of President Lincoln’s birth on February 12, 1909.

The task was assigned to the Army, which was then responsible for all national cemeteries. Army officials commissioned Rock Island Arsenal in Illinois to cast iron plaques inscribed with the speech. The project was delayed, however, due to uncertainty about which version of the address to use, as several different copies in Lincoln’s handwriting existed. Installation at the national cemeteries did commence in 1909 but not until after the date of his actual birthday. The tablets were massive, measuring nearly five feet tall and three feet wide and weighing close to 350 pounds. All-told, 77 cemeteries received a tablet. Additional tablets were later cast and erected at the handful of national cemeteries developed during the 1930s.

Over the years, time and the elements took their toll on the tablets and some were damaged while others went missing. In addition, dozens of new national cemeteries were established after 1945 as U.S. participation in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam produced a massive increase in the Veteran population eligible for interment in national cemeteries.

As the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth approached in 2009, VA initiated a program to add the Gettysburg Address tablet to every cemetery that lacked one. With funding from its Historic Preservation Office, VA worked with Rock Island Arsenal to manufacture replicas of the 1909 tablets. Fittingly, the original tablet at Rock Island National Cemetery served as the model for the lettering, form and materials of the reproductions. In the end, the new tablets were of such excellent quality that they could not be distinguished from the originals except by experts. To help tell them apart, VA asked the arsenal to cast a foundry mark on the reverse of each new tablet.

VA installed 62 of the new tablets in older cemeteries where the originals had been lost or damaged and in the national cemeteries dating from 1950 that never had one. Furthermore, every new national cemetery that opens has a Gettysburg Address tablet cast and installed prior to the cemetery’s dedication. The tablets, both old and new, are painted black with silver or white lettering.

In 2009, VA removed an original Gettysburg Address tablet mounted at Los Angeles National Cemetery that was showing wear at the corners and replaced it with a new one. Nine years later, the 1909 tablet found a new home in the lobby of VA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. Today, it serves as a reminder to everyone at VA of the enduring legacy of President Lincoln and the lasting importance of his words.

By Les' Melnyk

Senior Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.