National cemeteries originated out of necessity during the American Civil War. In the summer of 1862, as casualties mounted at an alarming rate, Congress empowered President Abraham Lincoln to purchase and enclose burial plots as national cemeteries to inter the growing number of Union dead. The National Cemetery Act of February 22, 1867, formalized details of the system and appropriated funds for temporary and then permanent features, including walls, grave markers, and “at the principal entrance of each of the national cemeteries…a suitable building to be occupied as a porters lodge.” The statute also funded the hiring of disabled Civil War Veterans as superintendents to live and work in the lodges.

The first lodges—small, inadequate, wood frame structures—were temporary. In the 1870s, the U.S. Army’s Office of the Quartermaster General, which was responsible for the cemeteries, began to replace the original lodges with standardized permanent lodges built in the French Second Empire style, popular from 1852 to 1870. The design represented federal authority in the South where many national cemeteries were located. Brigadier General Montgomery C. Meigs, the Quartermaster General from 1861 to 1882 and a brilliant engineer, oversaw this program.

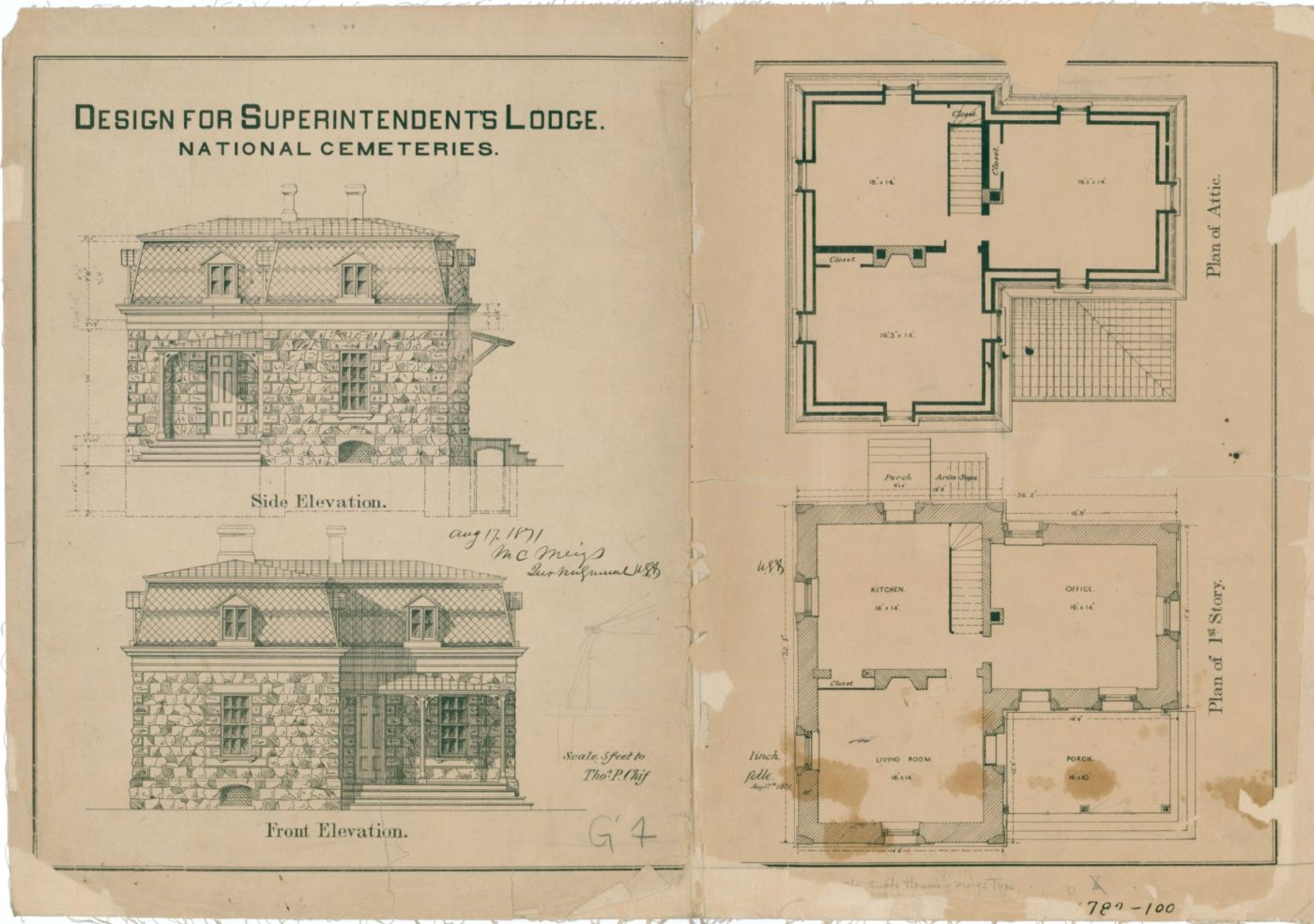

Edward Clark, who served under Meigs during the Civil War and afterwards became the Architect of the U.S. Capitol, designed them. Suggestions from superintendents led him to draft in 1869 a plan for an L-shaped building, one-and-a-half stories high, with six-rooms and a mansard roof. A prototype was erected in 1870 at the Richmond National Cemetery in Virginia. The layout was unique among Army construction at the time.

The L-shape segregated the superintendent’s living quarters from his workspace, with separate entrances for each. The mansard roof also subverted strict Army regulations about space allowances for lower ranks by creating unaccounted-for living space above the first floor. Thomas P. Chiffelle, a surveyor, engineer, quartermaster clerk, and West Point classmate of Meigs, drew the definitive version of the lodge in August 1871.

Government contractors built fifty-five such lodges in brick or stone between 1871 and 1881. Since the Quartermaster General was the final approving authority, they were often described as “Meigs’ lodges” or were said to be constructed according to the “Meigs Plan.” In the early twentieth century, the lodges were deemed antiquated and some were replaced; after 1950, the government stopped building new lodges.

Today, the National Cemetery Administration (NCA) has preserved eighteen French Second Empire lodges. Designated as historic resources, some are used as offices by NCA staff and other tenants. Despite being updated with plumbing, electricity and other modern touches, these iconic structures still serve as historical touchstones, reminding visitors of the post-Civil War origins of the national cemetery system.

Visit the National Cemetery Lodges: Documented for the Historic American Landscapes Survey website for more information.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.