On September 17, 1862, the Union Army turned back the Confederate offensive into Maryland at the Battle of Antietam. Five days later, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation announcing his intent to abolish slavery in the rebellious states as of the first of the year. On New Year’s Day, 1863, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, making good on his promise. The Proclamation transformed the character of the war. In addition to fighting for the restoration of the Union, Lincoln committed the nation to securing the freedom of the 3.5 million African Americans held in bondage throughout the South.

The Proclamation also gave Union military officials the green light to accept African Americans into military service, a policy Lincoln had previously been hesitant to endorse. Although Blacks had fought in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, after 1820 they were prohibited by law from enlisting in the Army. The Militia Act of 1862 relaxed this ban by granting the War Department limited authority to enlist “persons of African descent.”

The act applied not just to free Blacks in the North but also to “fugitives” and “contrabands” from the South—African Americans who had escaped their enslavers or taken refuge with the Union Army as it advanced into Confederate territory. The law led to the formation of the first regiments composed of Black soldiers. However, Lincoln still held off on calling for the unrestricted recruitment of African Americans for fear of antagonizing the slaveholding border states that had remained in the Union and the faction of northern Democrats who opposed the war.

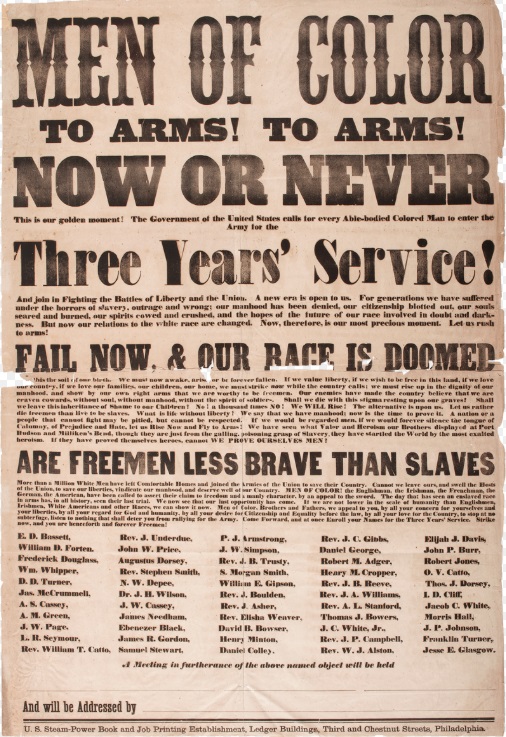

With the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln abandoned this cautious policy and the War Department launched an aggressive campaign to enlist “men of color.” Over the next two years, more than 200,000 African Americans joined the Union Army and Navy to fight in the Civil War. Occupied areas in the Confederate states proved to be particularly fruitful recruiting ground. About half of the Black volunteers came from the South. The widespread enrollment of African Americans provided the Union Army with a much-needed infusion of manpower, as war-weariness in the North slowed the pace of White enlistment.

Black soldiers were organized into U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) regiments led by White officers. At first, the Army relegated these units to fatigue duty, digging trenches, unloading supplies, and carrying out other low-skill tasks. Black privates also received lower wages than Whites and were issued surplus weapons and equipment. Many Union commanders believed African Americans were unsuited for combat because they lacked the discipline, intelligence, and fortitude to follow orders under fire. The performance of USCT regiments on the battlefield, however, quickly dispelled these racist notions about the inferiority of Black soldiers.

The Union attack on the Confederate stronghold at Port Hudson, Louisiana, in May 1863, served as one of the first tests of Black regiments in battle. They mounted three charges against the enemy’s earthworks and suffered heavy casualties in the face of withering fire. Although they failed to take the position, the regiments earned the admiration of the Union commanding officer, Major General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Afterwards, Banks wrote to his superior: “[T]he determined manner in which they encountered the enemy leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success.” In the final two years of the conflict, USCT units took part in 39 major engagements as well as several hundred smaller actions. Twenty-six African Americans received the nation’s highest award for valor, the Medal of Honor.

While Black soldiers proved they were the equals of Whites on the battlefield, after the war they struggled to receive equal treatment from the Federal Government. The laws governing pensions for Veterans of earlier wars were color-blind and the General Pension Law enacted by Congress in 1862 was no different. In theory, Blacks with service-connected disabilities were eligible to apply for the same benefits as Whites.

But the pension system was far from egalitarian in practice. Recent studies based on the service and pension records of thousands of men have shown that African Americans were less likely to submit claims or have their applications approved. And when they were granted a pension, their disabilities were judged to be less severe, leading to lower cash awards.

Several factors contributed to the disparity in outcomes. African American Veterans often encountered significant obstacles gathering the records needed to prove their injuries or illnesses were related to their military service. Some were also too poor to afford a pension attorney to help them prepare an application. The fact that many formerly enslaved ex-soldiers from the South were illiterate compounded the challenges of documenting their claims and navigating the complexities of the pension system. Finally, African American applicants had to surmount the racial prejudices of the medical examiners and Pension Bureau clerks.

Thousands of deserving Black Veterans still successfully pursued their claims and received compensation for the wounds or illnesses they suffered while wearing the Union uniform. They also enjoyed greater success obtaining a pension under the more liberal 1890 Pension Act, which eliminated the requirement for the disability to be service-related. Research suggests that the reward was well worth the effort. African Americans who secured a pension lived longer than those without. They were also more likely to own a house and be able to retire and live independently in their old age.

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.