From World War I through Vietnam, more than 1,000 Americans were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest decoration for valor. The wall display outside the offices of VA’s Under Secretary for Benefits in Washington, D.C., pays tribute to a select group of them: the 98 recipients who after serving their country chose to serve their fellow Veterans by going to work for VA. Their names are inscribed on metal plates affixed to the large plaque at the bottom of the display, organized by conflict and then alphabetically (with the exception of a few names at the end).

VA exhibit designer William Hester, Jr., researched and built the display sometime around 2010. The prolific Hester, who worked at VA for close to 40 years before retiring in 2015, created by his own estimate about 400 exhibits at VA facilities and other locations over the course of his career.

The service members who received the Medal of Honor for acts of bravery during World War II make up more than half of the names on the plaque. The VA tripled the size of its workforce after the war and General Omar N. Bradley, who became head of the agency in 1945, actively recruited Veterans to fill out its ranks. All-told, about one in eight Medal of Honor recipients from the World War II generation ended up finding employment at VA.

Hershel “Woody” Williams was one of these new hires. Serving as a demolition sergeant with the 3d Marine Division, Williams earned his decoration for almost singlehandedly destroying a Japanese pillbox nest during the Battle of Iwo Jima in 1945. The savage month-long campaign to secure the small island in the Pacific cost the Marines over 25,000 casualties and produced 27 Medal of Honor awardees, the most of any single operation in U.S. history.

Following his discharge from the military, Williams returned to his native state of West Virginia. He had just started working as a supply officer in an engineering firm when VA offered him a position as a contact representative in its West Virginia regional office. The starting salary was five times higher than his monthly pay in the Marine Corps, which made the decision to accept the offer an easy one. As he later recalled in an interview, however, the rewards of the job went well beyond the material.

“After I got involved and was able to, most days, do something to assist people that maybe would have never received that assistance, you’d always come home in the evening feeling good and anxious to get back to work the next morning because you knew that you were going to be able to do something that would help somebody,” he said. The satisfaction of aiding other Veterans on a near daily basis sustained him through thirty years of public service. He retired from VA in 1976.

Many of Williams’ fellow Medal of Honor recipients from the war followed him into the same line of work at VA. As contact representatives, they met with Veterans and their dependent and counseled them about the different benefit programs available to them. Most were based at VA regional offices, which served Veterans seeking benefits in designated geographic areas. During the Vietnam War, a few contact representatives had the opportunity to trade their civilian clothes for combat fatigues and spend three months in South Vietnam advising soldiers preparing to separate from the Army.

Marine Veteran Robert E. Bush, who received his Medal of Honor at the same White House ceremony as Hershel Williams, volunteered to join the first team of contact representatives participating in the program, which started in 1967. Bush earned his medal leading his squad on an assault in the face of withering enemy fire on Okinawa in 1945.

While being treated for his wounds after the attack, he threw himself on a grenade to protect the men around him, an act of self-sacrifice that cost him several fingers and the use of one eye. Bush was located at the Chicago regional office when he took the assignment to go to Vietnam. Hershel Williams, fittingly enough, led the second team of volunteers that arrived three months later.

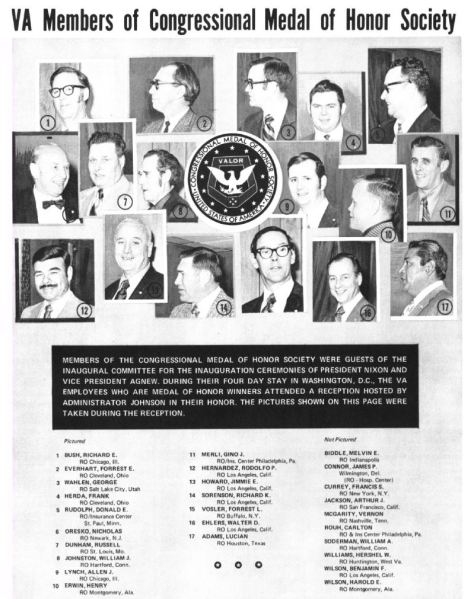

While the agency’s Medal of Honor awardees worked at VA facilities in many different parts of the country, they were able to assemble as a group on occasion. In May 1963, President John F. Kennedy invited all holders of the medal to his annual reception for the military at the White House. Seventeen VA employees made the trip to Washington along with their wives and they met with VA’s deputy administrator at the agency’s D.C. headquarters prior to the event.

Ten years later, an identical number of recipients attended a reception at the headquarters building hosted by VA’s chief administrator during the 1973 presidential inauguration ceremonies. Williams was absent, but the contingent included Bush and another medical corpsman who received his decoration for “conspicuous gallantry” during the grim fighting for Iwo Jima, George E. Wahlen. Notably, Medal of Honor recipients from more recent conflicts were also present. Two Korean War and three Vietnam War Veterans were on hand for the VA gathering that day.

The passage of time took its toll on the Medal of Honor recipients in VA’s ranks and, by the early 1990s, only eleven were still working at the agency. By 2002, the number had dwindled to seven. All had served in Vietnam. Among the last of these stalwarts was Robert L. Howard, who was one of the war’s most decorated soldiers.

He earned his Medal of Honor as a Special Forces sergeant on a mission in enemy-controlled territory to locate a missing soldier in 1968. When his platoon of Green Berets came under heavy attack, he rallied his troops and directed the defense of their perimeter despite being badly wounded himself. Howard joined VA relatively late in life after completing a 36-year career with the Army and retiring as a colonel in 1992. He died in 2009.

Note: Since publication of this entry, we have learned that the plaque does not include the name of Vietnam War Medal of Honor recipient Harold A. Fritz, who worked as a Volunteer Service Specialist in the VA Illiana Health Care System in Illinois.

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.