Fixing the benefits system, results in Veterans Bureau

When he accepted the Republican nomination for president in 1920, Warren G. Harding issued a solemn promise to the more than four million Americans who had served in the U.S. armed forces during what was then simply called the World War: “It is not only a duty, it is a privilege to see that the sacrifices made shall be requited, and that those still suffering from casualties and disabilities shall be abundantly aided and restored to the highest capabilities of citizenship and enjoyment.”1

At the time of the election, dissatisfaction with the benefits programs for World War I Veterans ran rampant throughout the country. Discharged soldiers, influential Veterans groups such as the 800,000- strong American Legion, politicians, and the press alike agreed that the current system was, if not broken, in dire need of reform.

The over 200,000 service members who returned from the war with physical or mental ailments were eligible for several different types of benefits, but they had to navigate the bureaucracies of three different federal agencies to receive them: the Bureau of War Risk Insurance (BWRI) for insurance and compensation, the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) for medical and hospital care, and the Federal Board for Vocational Education for rehabilitation, education, and job training.

In the eyes of its critics, this system was not only confusing and inefficient, but it also failed to deliver to disabled Veterans the benefits and services that were their due. All insurance and disability claims had to be processed by the BWRI central office in Washington, DC, and the staff struggled to keep up with the 20,000 or more requests that flooded the mail room on average each month.

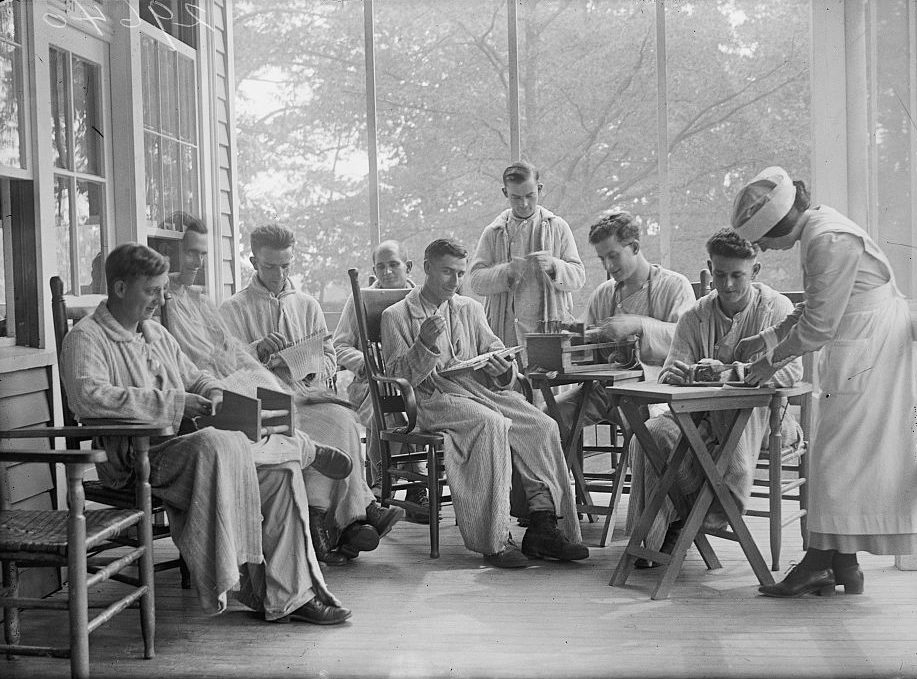

The PHS also came under fire for the quality of the hospital services it provided. The agency relied on a patchwork network of government-owned or leased hospitals supplemented with beds contracted at civilian hospitals, but conditions in these facilities varied widely. Furthermore, the demand for care exceeded the supply. A 1920 report estimated that another 10,000 beds would be needed in the upcoming fiscal year, primarily for Veterans suffering from tuberculosis and psychological illnesses. Finally, the vocational training made available to disabled Veterans at commercial schools, factories, businesses, and other private facilities produced few positive results. Only a small fraction of the over 200,000 beneficiaries eligible for rehabilitation actually completed their assigned program.

Harding won the 1920 election in a landslide and after his inauguration in March 1921, his administration took on the task of fixing the defects in the benefits system.2 The presidential committee he appointed in April 1921 required just a few days of hearings to identify the root of the problem: “The principal deplorable failure on the part of the government to properly care for the disabled Veterans is due in large part to an imperfect organization of government effort.” The solution? The committee recommended consolidating the programs for disabled Veterans of the World War into an independent federal agency led by an executive who reported directly to the president.

Congress took up the committee’s proposal and by summer passed Public Law 67-47, popularly known as the Sweet Act after the name of the legislator who introduced it, establishing the Veterans Bureau. Harding signed the bill into law one hundred years ago this week, on August 8, 1921. The next day, he named Charles R. Forbes, a personal friend and decorated war Veteran who was currently running the BWRI, as the bureau’s first director.

Evolution

In its first annual report submitted to Congress in 1922, the new agency hailed its creation as “one of the epochs of Veteran relief.”3 While that was perhaps overstating the case, the founding of the Veterans Bureau did mark an important stage in the evolution of the benefits system. With the stroke of a pen, Harding brought into existence a vast new organization with broad powers, expansive responsibilities, and a budget that was one the largest in the federal government.

The bureau’s central office staff of 5,000 occupied the 10-story building on Vermont Avenue in Washington, DC, that had been built in 1918 to serve as the headquarters for the now defunct BWRI. Another 25,000 men and women worked in field offices, hospitals, and schools spread across the country.

As part of its plan to decentralize operations, the bureau delegated considerable authority to the 14 district offices it established. These offices could assign disability ratings and adjudicate claims and make decisions regarding medical care and vocational training. Their activities were supported by more than a hundred sub-district offices (see accompanying story on the Winston-Salem Regional Office) that offered a more limited range of services, including physical exams. Another important function was to serve as a first point of contact for former service members and assist them in the filing of claims and obtaining other benefits.

The Veterans Bureau did not absorb all government services for Veterans. The Pension Bureau, the agency in the Department of Interior that administered pensions for soldiers and sailors from earlier conflicts, remained separate. The same held true for the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, the network of residential facilities established after the Civil War to provide long-term care for infirm or indigent Union Veterans. These entities would eventually be combined with the Veterans Bureau by executive order in 1930 to form the Veterans Administration.

Forbes and his staff at the Veterans Bureau set out to do more than streamline operations and improve the efficiency of the organization. They also strove to provide better care and services. The bureau devoted considerable attention and resources to remedying one of weakest elements in the benefits system: vocational rehabilitation. It subjected schools and other establishments that worked with disabled Veterans to close oversight and adopted new standards and policies for how these training programs were to be conducted. The Veterans Bureau also operated its own residential and non-residential vocational schools, but this experiment was short-lived and most closed their doors after just a few years.

The Veterans Bureau’s most enduring impact came through its efforts to expand Veteran access to medical care. The agency in early 1922 inherited a number of medical clinics from the Public Health Service. At Forbes’ doing, it added many more. Forbes wanted to establish a clinic at every district and subdistrict office. By the middle of 1922, the bureau was well along its way towards meeting this goal, with close to 100 clinics up and running. These clinics varied in size and services, but even the smaller facilities offered medical and dental treatment, x-rays, and a clinical laboratory.

Forbes also championed an ambitious program of new hospital construction. His insistence that the Veteran Bureau control the $17 million appropriated by Congress in 1922 for this purpose brought him into conflict with powerful officials within the administration. The program was controversial for other reasons as well, but in the space of three years it produced 13 additional hospitals and over 4,000 more beds, three-fourths of which were in facilities specifically designed to treat patients with neuropsychiatric problems. Hospital capacity had increased to such an extent that Congress in 1924 agreed to permit Veterans of any conflict since 1897 to seek care in one of the bureau’s hospitals, even for conditions that were not service related.

Forbes himself lasted less than two years on the job. He resigned in 1923, worn down by his responsibilities and hounded by accusations of waste and misconduct. In 1926, he was convicted of conspiring to defraud the federal government, largely on basis of the testimony of a shady businessman and bootlegger who had been frustrated in his own attempts to profit from his relationship with Forbes.

The scandal, however, failed to slow the growth of the Veteran Bureau’s health system. Under the leadership of Forbes’ successor, Frank T. Hines, the agency added new medical facilities and services. By the time the Veterans Administration replaced the Veterans Bureau in 1930, the vast majority of sick and disabled Veterans were able to receive treatment in government clinics and hospitals that were operated expressly for their care.

See our Winston-Salem Regional Office, VBA History article for additional information.

Footnotes

- Quoted in Annual Report of the Director, United States Veterans’ Bureau for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1922 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1922), p. 6-7. ↩︎

- Quoted in Rosemary Stevens, A Time of Scandal: Charles R. Forbes, Warren G. Harding and the Making of the Veterans Bureau (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), p. 49. ↩︎

- Annual Report, FY 1922, p. 6. ↩︎

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

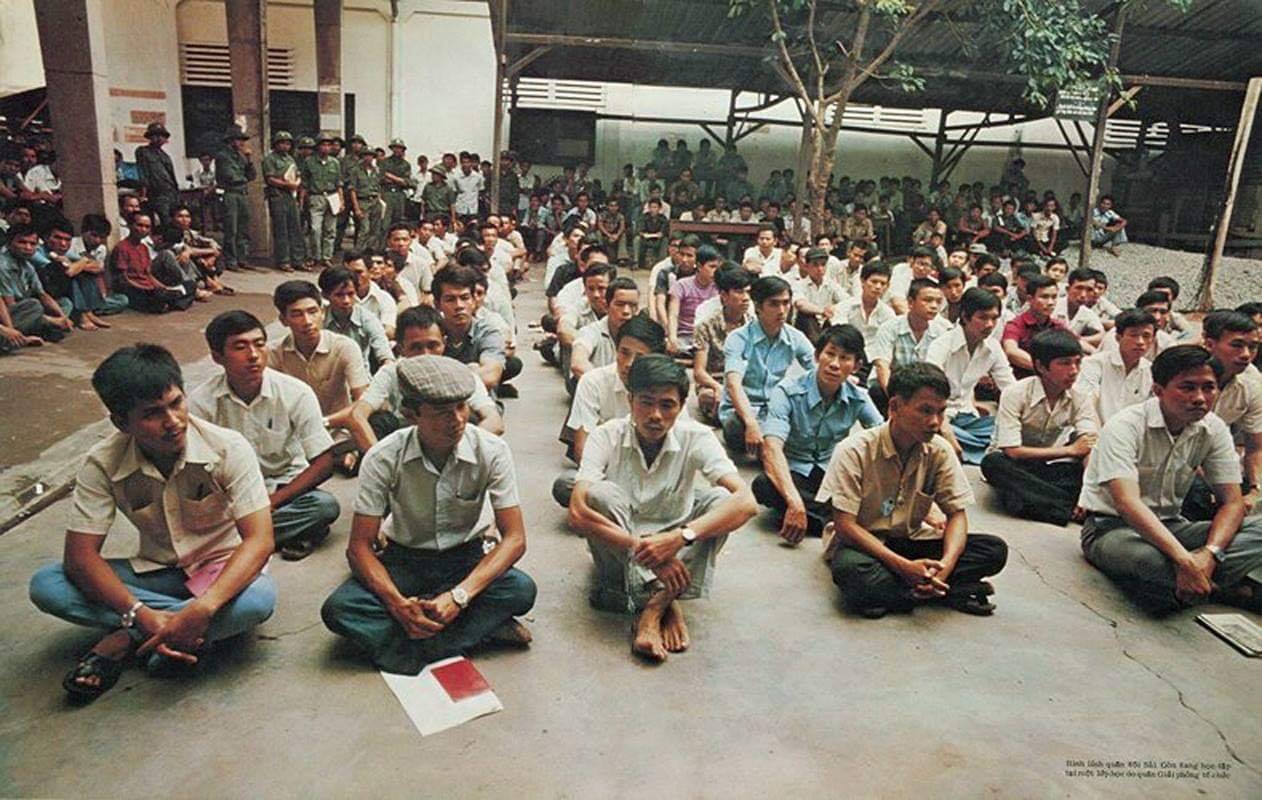

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."