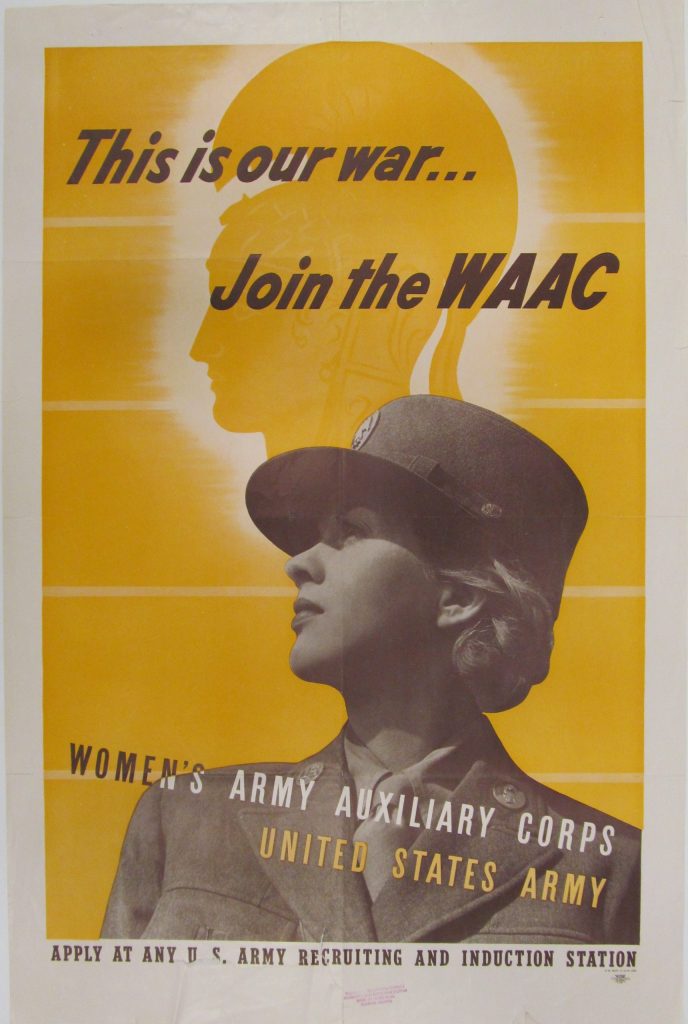

With Europe once again at war in late 1939, Americans pondered whether the United States would join the fight on the Allies’ side and, if so, would women be allowed to serve in the military. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 decided the first issue. But the second question remained in doubt for months afterwards. At the time of the U.S. declaration of war, a bill to establish a Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was already pending in Congress.

It had been introduced in May 1941 by Edith Nourse Rogers, the crusading Congresswoman from Massachusetts. Despite attracting the support of the Army Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, the bill made little headway in Congress until after Pearl Harbor. The measure still encountered fierce resistance from some male legislators who wanted to keep women out of the military altogether, but a revised version finally passed in May 1942.

Women had proven their worth during the First World War, serving as nurses in the Army and Navy and as clerical workers in the Naval and Marine Corps Reserve. Some 10,000 Army nurses served overseas in hospitals and field units, often under dangerous conditions, but they held no military rank or grade and were not entitled to the same pay, privileges, and benefits as men. At the beginning of World War II, Rogers fervently hoped to see women admitted into the Army’s ranks on the same footing as men.

However, she recognized that she had no chance of persuading the War Department or Congress to adopt such a plan. Consequently, she settled for auxiliary status. As the original bill stated, the WAAC was “not a part of the Army but it shall be the only women’s organization [other than the Nurse Corps] authorized to serve with the Army.”

Even in this water-downed form, the creation of the WAAC still represented a step forward for women, as it expanded the roles open to them within the service. At the same time, their non-military status left them vulnerable when stationed abroad, as they received no overseas pay, life insurance, disability benefits, or death gratuity (for their families) if killed in action.

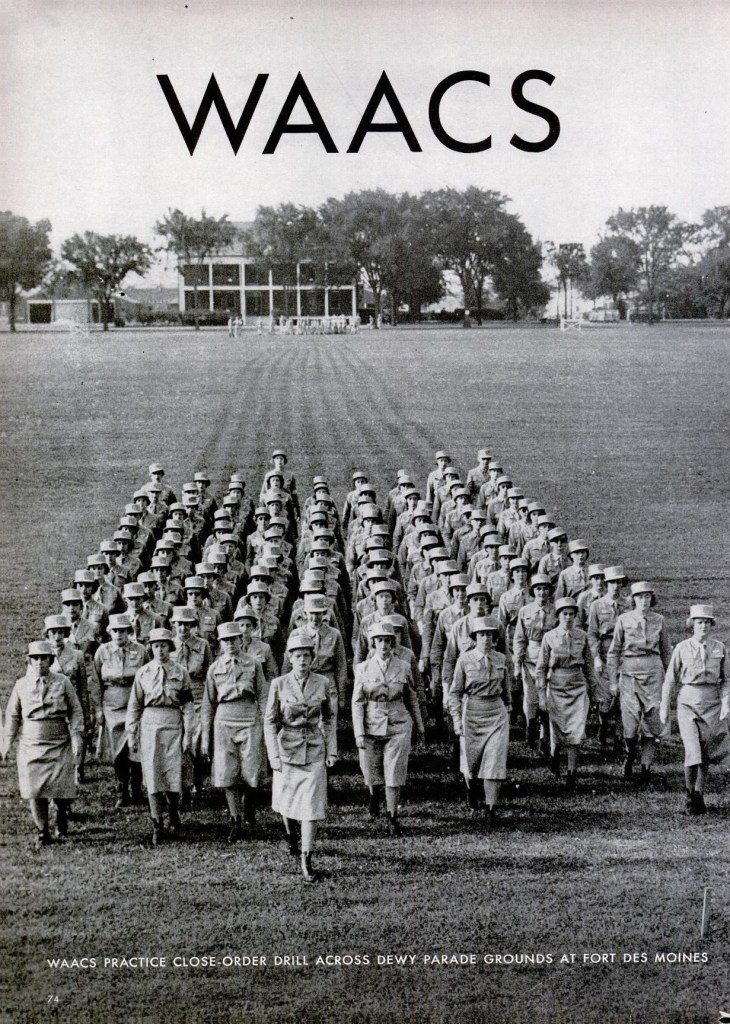

Training for WAAC officer candidates and WAAC auxiliaries (the female equivalent of privates) got underway in the summer of 1942 at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. The Director of the WAAC, Oveta C. Hobby, advised the first class of officer recruits: “You have taken off silk and put on khaki.” The press and the public were fascinated by the cultural aspects of WAAC service.

At her first press conference, reporters peppered Hobby with questions about attire (girdles would be issued if required), the wearing of makeup and nail polish (yes, in moderation), and the carrying of firearms (no). While some of the early coverage was sexist and dismissive, the WAACs also received positive press. Life magazine, one of the most popular periodicals of the day, published a flattering photo essay on the WAAC trainees at Fort Des Moines. The story highlighted their professionalism and patriotism and delivered a clear message about the importance of their service: WAACs were freeing up male soldiers who were desperately needed for combat duty.

While skepticism about their capabilities followed the WAACs into the ranks, Army leaders readily recognized their value. Before the first female auxiliary graduated from basic training, more than 80,000 requisitions for their services had been received from Army field commands. In November, the War Department secured the president’s approval to accelerate recruitment and increase the size of the corps to 150,000, the maximum permitted by law.

Army officials also revised their original plans to employ WAACs primarily in clerical positions; instead, they were permitted to serve in hundreds of non-combat military specialties. Although many did work as clerks and typists, others became radio operators, parachute riggers, truck drivers, surgical technicians, and cryptologists, to name just a few of the jobs they performed.

By the beginning of 1943, the head of the Army, Gen. Marshall, was ready to declare the WAAC experiment a success: “Although the Corps is still in the formative period of organization, its members have convincingly demonstrated their ability to render a vital military service.” However, their non-military status was a barrier to their employment overseas and also caused more than a few administrative headaches for the Army.

In February, the War Department endorsed a new bill proposed by Congresswoman Rogers that did away with women’s auxiliary status and made the corps part of the Regular Army. On July 1, 1943, the bill establishing the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) became law. About three-fourths of the 60,000 women currently enrolled in the WAAC chose to continue their service and join the WAC.

By the war’s end, the size of the WAC had grown to almost 100,000 and women had deployed to every major theater of operations, from the Middle East to the Southwest Pacific. For the first time, women held military rank just like their male counterparts and were granted the same allowances, privileges, and protection. Their relatively equal treatment continued after their discharge, as WACs qualified for the GI Bill and other benefits extended to male Veterans. In 1948, the government ended any questions about the right of women to serve by authorizing their enlistment and appointment in the active and reserve components of all branches of the armed forces.

By Maureen Thompson, Ph.D.

Historian, Central Alabama VA Medical Center-Tuskegee

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 93: Occupational Therapy Floor Loom

During World War I and afterwards, the United States committed to rehabilitating sick and wounded soldiers so they could resume productive lives in the civilian workforce. The emerging field of occupational therapy played a crucial role in the rehabilitative process.