In World War I, spinal cord injuries resulting in paralysis of the lower body almost always led to an early death. According to one authority, only ten percent of the American soldiers who reached a U.S. medical facility after suffering such an injury on the battlefield lived for longer than a year. Many succumbed to sepsis or infection. Those who were lucky enough to beat the odds faced the prospects of a life that was, in the words of a medical expert writing in 1932, “of little value to the patient and costly to his relatives.”

During World War II, however, medical and technological advancements reduced the lethality of traumatic injuries to the spinal cord. The discovery and mass distribution of penicillin and sulfa tablets lowered the risk of infection for soldiers with all types of wounds. In addition, improvements in the capabilities of portable surgical hospitals enabled medical personnel to perform emergency procedures and operations close to the battlefield. Afterwards, military transports could airlift the seriously wounded to stateside hospitals for long-term treatment and recovery. Faster and better medical care are for casualties helped an estimated 2,500 paralyzed U.S. service members survive their injuries and return home from the conflict. After the war, most continued their recuperation and rehabilitation in VA hospitals.

While VA offered paraplegic Veterans a healthy dose of physical and occupational therapy as well as vocational training, patients craved something more. They also wanted to engage in the sports that they had grown up playing. They were limited at first by their wheelchairs, which were incredibly bulky and commonly weighed over 100 pounds. However, the revolutionary wheelchair design created by engineers Herbert A. Everest and Harry C. Jennings in the late 1930s solved that problem. Their chairs featured lightweight aircraft tubing, rear wheels that were easy to propel, and front casters for pivoting. Weighing in at around 45 pounds, the sleek wheelchairs were ideal for sports, especially basketball. The mobility of paraplegic Veterans drastically increased as they mastered the use of the chair, and they soon began to roll themselves into VA hospital gyms to shoot baskets and play pickup games.

In 1946, at the Birmingham VA Hospital in Van Nuys, California, physical education teacher Robert D. Rynearson observed paralyzed Veterans joyfully trading shots on the basketball court. He quickly recognized the value of the sport as a therapeutic activity. The hard flat surface of the court was ideally suited for players maneuvering in wheelchairs, the game could be played year round, and it strengthened the upper body muscles so essential to those who had lost the use of their legs. Rynearson started organizing practices for the players and also drafted a set of ten rules for regulated play. In adapting the sport to the wheelchair bound, Rynearson endeavored to preserve the speed and spirit of the game while ensuring the safety of the players. He determined that incidental contact between the chairs of two players was allowed, but intentional ramming would be considered a foul. Additionally, players were permitted two pushes of the wheelchair when in possession of the ball. He also considered altering the height of the basketball rims and the distance from the free-throw line, but the Veterans convinced him to keep these elements of the game the same.

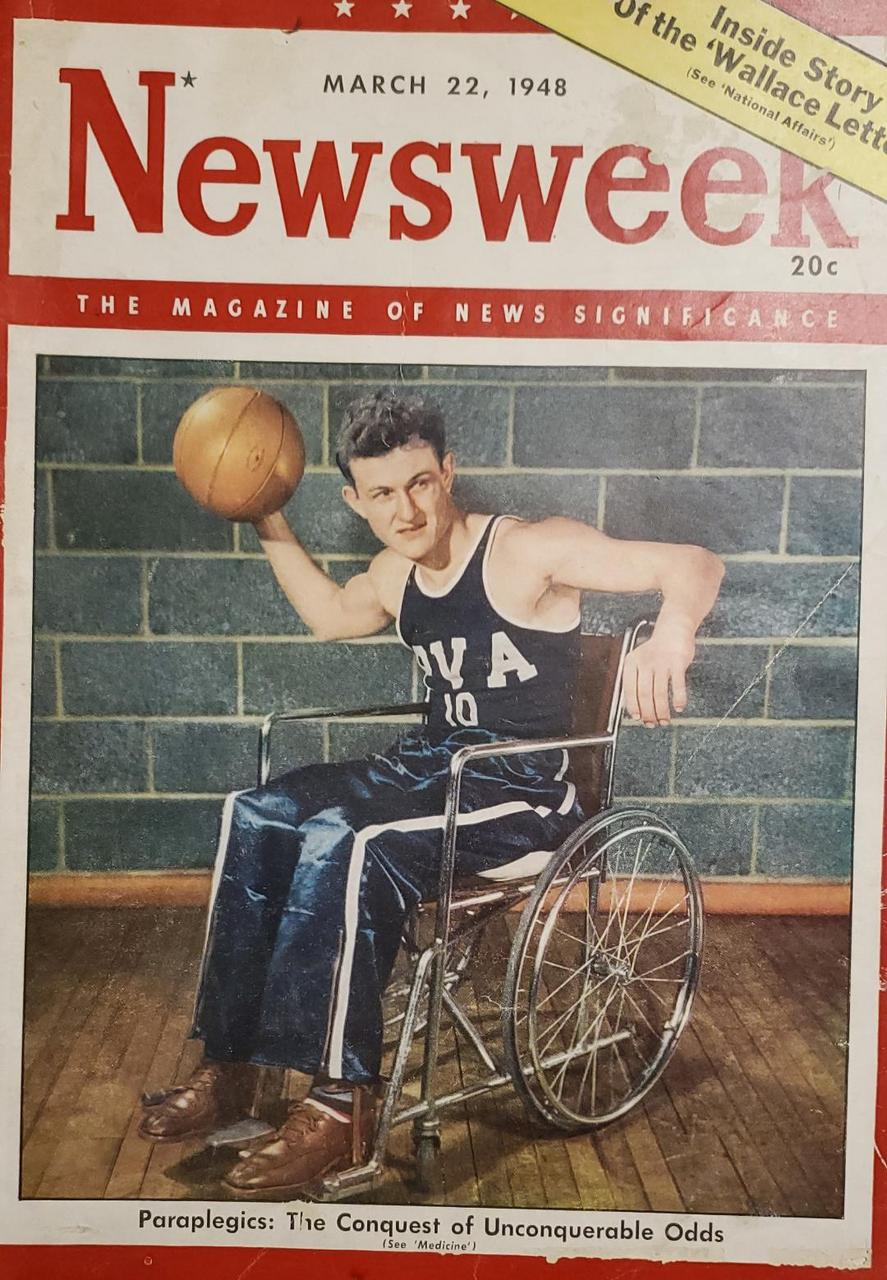

Rynearson held the first official wheelchair basketball contest on November 25, 1946, at the Birmingham VA Hospital. His team of paralyzed Veterans faced off against a group of non-disabled doctors in wheelchairs, beating them 16-6. The hospital’s in-house newsletter described the game as “an action-packed, fast-moving and exciting contest.” Soon after, other groups of Veterans formed wheelchair basketball teams at VA hospitals around the country. Teams like the Rolling Devils and the Gizz Kids garnered national attention, playing before packed crowds and easily dispatching non-disabled college and professional teams who borrowed wheelchairs for the games. National news coverage grew with the increasing popularity of the game, and their exploits were featured in publications ranging from The New York Times to Daily Worker. One standout player, Jack Gerhardt, a paratrooper wounded at Normandy in 1944, appeared on the cover of the March 22, 1948, issue of Newsweek. The cutline below his photo read: “Paraplegics: The Conquest of Unconquerable Odds.” His jersey bore the letters PVA, which stood for Paralyzed Veterans of America, the group founded in 1946 to combat stereotypes and advocate for people with disabilities.

Players on the Birmingham VA team did their part to fight for disability rights. In 1948, under the name Flying Wheels, they embarked on a barnstorming tour that included stops at eight major cities, where they played in big arenas before packed crowds against other teams of paraplegic Veterans and non-disabled players. After going against the squad from the VA hospital in Richmond, Virginia, the Flying Wheels traveled to the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. They wheeled through the Capitol’s halls to lobby Congress for legislation that would allow paralyzed Veterans to buy homes accessible for wheelchairs. The Flying Wheels were successful: the Specially Adapted Housing Act became law on June 19, 1948.

In late 1948, the National Wheelchair Basketball Association was established to oversee games and arrange an annual tournament. Over time, polio survivors, amputees, and other men, women, and adolescents with disabilities also took up the game and formed teams. The sport launched by paralyzed Veterans at VA hospitals after World War II is now played the world over, enabling disabled athletes everywhere to enjoy the thrill and pleasure of competition on the court.

By Emme Richards

Virtual Student Federal Service Intern, VA History Office, Department of Veterans Affairs

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.