Protecting a territorial capital to today’s Bob Stump VA hospital

The present-day Bob Stump VA Medical Center campus in Prescott, Arizona has had a long and interesting history from the time the Arizona Territory was created in 1863.1

In May 1864 the site was first established as Fort Whipple. Located on the banks of Granite Creek, this site was selected by John Noble Goodwin, the first governor of the Arizona Territory. The troops at Fort Whipple protected the settlers and miners in and around the newly established territorial capital of Prescott.2 Prescott served as the territorial capital from 1864 to 1867. The capital was then relocated to Tucson, but returned to Prescott again from 1877 to 1889. In February 1889, the capital was permanently moved to Phoenix.3

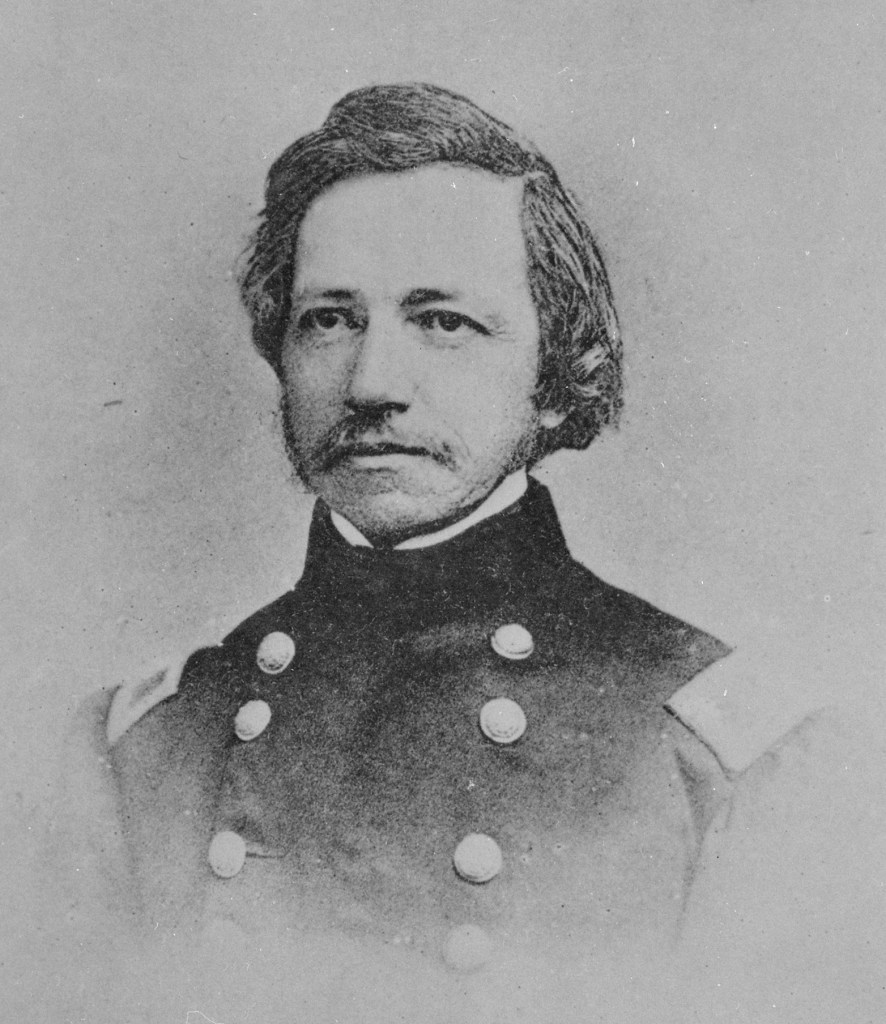

The fort was named in honor of Amiel Weeks Whipple, an American military officer and topographical engineer.4 Whipple surveyed the new U.S./Mexico boundary (1848-1851) and a transcontinental railroad route (1853-1854). He served as a brigadier general in the American Civil War and was mortally wounded on May 7, 1863 at the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia.

From 1864 to 1886, Fort Whipple and other forts in the West served as tactical bases for U.S. Army regiments involved in the American Indian Wars.5 Lieutenant Colonel George Crook was assigned to Fort Whipple and used Apache Scouts to address escalating territorial problems.

The fort, now called Whipple Barracks, was scheduled to be deactivated in late 1897.6 The plan was delayed when the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898 and Whipple Barracks served as a mobilization point for the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry.7 Nicknamed the “Arizona Rough Riders” and led by William “Buckey” O’Neill, these volunteers fought in Cuba in the Spanish-American War. After the war ended in August 1898, the fort was deactivated.

In 1902, with strong lobbying from Prescott and Arizona Territory politicians, the War Department approved the reconstruction of Whipple Barracks.8 Twenty-three new buildings were constructed between 1903 and 1908. These buildings included officers’ quarters, troop barracks, an administrative headquarters, a guard house, a wagon shed, a reservoir, a post hospital and a post exchange. The revitalized Whipple Barracks remained active and was an integral part of Prescott. On February 14, 1912, Arizona achieved statehood.9

In 1913, the War Department designated Whipple Barracks obsolete. Troops were re-assigned and Whipple Barracks was placed in an un-garrisoned/caretaker status.10 While Whipple Barracks remained unused, World War I was occurring on the other side of the globe. The use of nerve gases in warfare brought about the need to treat soldiers suffering from lung disease including tuberculosis. As a result in 1918, Whipple Barracks was reactivated to become U.S. Army General Hospital #20.11

The mile-high elevation of Whipple Barracks and Prescott provided a favorable location to treat patients with tuberculosis. Barracks were converted to tuberculosis wards to handle the influx of military patients. Prescott itself had several sanatoriums to treat non-military patients.12 The hospital facility experienced a transition period that started in 1920 as Congress expanded the role of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS).

Early in 1920, the Secretary of War loaned Whipple Barracks to PHS to continue as a hospital for returning soldiers from World War I. Later that year, PHS officially took control and re-designated Whipple Barracks as PHS Hospital #50. PHS controlled forty-two other medical facilities in the U.S. which were categorized into general, neuro-psychiatric, or tuberculosis hospitals. Whipple Barracks maintained its tuberculosis designation. Numerous new structures and tuberculosis wards were built, which increased the bed count to 900. The facility became one of the most complete tuberculosis sanatoriums in the country.13

On April 29, 1922, President Harding issued Executive Order 3669 and transferred fifty-seven hospitals from PHS to the Veterans Bureau. Whipple Barracks, Arizona was one of these hospitals. The Veterans Bureau provided funding to Whipple Barracks as part of the First Langley Act.14

On July 21, 1930, consolidation of several veterans’ agencies including the Veterans Bureau took place as President Hoover signed Executive Order 5398 to create the Veterans Administration. The official transfer of title from the War Department to the VA for Whipple Barracks occurred on March 3, 1931. The March 4, 1931 edition of the local newspaper, the Prescott Evening Courier stated “the transfer of title is now law and telegrams of this announcement were sent to Arizona Congressmen, the Yavapai County Chamber of Commerce, and representatives of local Veterans’ organizations.”15

In April 2004, the hospital was re-named the Bob Stump VA Medical Center, honoring Congressman Robert “Bob” Lee Stump from Arizona (U.S. House of Representatives from 1977 to 2003).16

Today’s campus is a mix of historical buildings and other modern buildings built from the 1950s to the present. Certified on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999 by the National Park Service, the historic name of Fort Whipple is listed as “Fort Whipple/Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center Historic District.”17

The history of Fort Whipple to the present-day Bob Stump VA Medical Center is presented on the campus at the Fort Whipple Museum (opened in 2004) and at the Northern Arizona VA Health Care System Historical Wall (dedicated in 2017).18 The museum is in one of the historic officers’ quarters, Building 11. The Historical Wall is located along an interior corridor between the main hospital building (Building 107) and Community Living Center (Building 148).

Footnotes

- February 24, 1863 –President Lincoln Signed the Arizona Organic Act ↩︎

- Wagoner, Jay J.Arizona Territory 1863-1912 A Political History. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1970. Page 36. ↩︎

- Capitals of the Arizona Territory and State ↩︎

- 11 April 1898, Page 8 – The Arizona Republican, Expedition along the 35th parallel led by Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple (July 1853- March 1854), Amiel Weeks Whipple and the boundary survey in southern California ↩︎

- Wagoner, Jay J.Arizona Territory 1863-1912 A Political History. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1970. Pages 84, 103, 134. Trimble, Marshall Arizona: A Panoramic History of a Frontier State. Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1977. Pages 182-201. ↩︎

- 8 December 1897, page 2 – Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner, 15 December 1897, page 2 – Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner, 30 March 1898, page 2 – Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner, 6 April 1898, page 1 – Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner. ↩︎

- 11 May 1898, Page 1 – Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner ↩︎

- 11 April 1902, Page 1 – Arizona Republic ↩︎

- The Statutes at Large Part 2 page 1728 ↩︎

- 19 February 1913, Page 2 – Weekly Journal-Miner ↩︎

- 20 March 1918, Page 4 – Weekly Journal-Miner, 22 May 1918, Page 4 – Weekly Journal-Miner ↩︎

- National Register of Historic Places Registration Form – Pine Crest Historic District, July 1989, Section number 8, page 5 and 6, 24 April 2010 – The Daily Courier ↩︎

- 21 January 1920, Page 2 – Weekly Journal-Miner, 18 February 1920, Page 5 – Weekly Journal-Miner ↩︎

- Veterans Bureau Annual Report, FY1922 (PDF, 369 pages) ↩︎

- 4 March 1931, Page 1 – Prescott Evening Courier ↩︎

- S.1511 – 108th Congress (2003-2004) – A bill to designate the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Prescott, Arizona, as the “Bob Stump Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center” ↩︎

- National Register of Historic Places Registration Form – Fort Whipple/VAMC, October 1999 ↩︎

- 23 May 2004 – The Daily Courier at dcourier.com, 28 December 2018 – The Daily Courier, 1 November 2017 – The Daily Courier ↩︎

By Mary Dillinger, Public Affairs Officer, VA Northern Arizona Healthcare System and Worcester Bong, Health System Specialist to Chief of Staff and Facility Planner (retired)

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."