On May 12, 1868, Dorothea L. Dix transferred ownership of the newly installed monument at Hampton National Cemetery in Virginia to the U.S. Army. Dedicated to “Union Soldiers who perished in the War of the Rebellion,” the 65-foot-tall granite obelisk is among the largest and earliest Civil War memorials in VA’s national cemetery system.

After the war, Army officials consolidated the graves of all Union soldiers in southeastern Virginia at the Hampton site. However, plans to erect a monument there using private donations almost failed until Dix—renowned social reformer, mental health advocate, and Superintendent of Army Nurses during the Civil War—took charge of the effort. Credit for the Union Soldiers’ Monument belongs entirely to Dix. Through her determined fundraising and generosity with her own time and money, she rescued the faltering memorial project and shepherded it to completion.

Union chaplains James Marshall and Edward P. Roe at the Fort Monroe military hospital conceived of the idea of raising a monument for soldiers at the nearby cemetery in early 1865. They established a fundraising board that included themselves and the assistant surgeon. However, the publication of two circulars in national newspapers soliciting donations raised only $1,000, well short of their $4,000 goal.

In the spring of 1866, the board sought out Dix, who had close associations with the Fort Monroe hospital. She personally pledged $1,000 and quietly secured another $3,000 in donations. By August 1866, the board officially dissolved and asked Dix to assume responsibility for “carrying forward and completing the monument.” Within two months, based on personal connections alone, Dix collected $7,900. Now flush with funds, she worked with Army engineers to visit northeast quarries and solicit bids. Soon after, she entered into a contract for granite with Ira Andrews of Biddeford, Maine, who agreed to deliver the materials to Hampton by April 1867.

Dix originally planned for a modest 30-foot-tall obelisk. The money raised would be sufficient to cover the costs of quarrying and transporting the granite to Hampton and constructing the actual monument. In the summer of 1866, however, Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs committed the Army to paying for the transportation and construction, since the monument upon completion would be gifted to the U.S. government.

This arrangement allowed Dix to increase the monument’s height to 75 feet, with a base nearly 20 feet square. It also gave her the financial resources to pay for more ornamentation: a high-relief U.S. coat-of-arms with a life-size eagle on the front, and three other panels inscribed with a cross-cannon (artillery), cross-sabre (cavalry), and cross-rifle (infantry). Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Thomas J. Treadwell, serving as Principal Assistant to the Army’s Chief of Ordnance, suggested the addition of large block dates to accompany the imagery to signify different periods of the war.

The inscription below the face panel—“In memory of Union Soldiers who died to maintain the Laws”—was inspired by the classical Greek couplet honoring the Spartan warriors who died at the Battle of Thermopylae: “Go tell in Lacedaemon [Sparta] these died to maintain the laws.”* The completed monument weighed 700 tons. Dix hoped to place it on a sand ridge surrounded by live oak trees a mile north of Fort Monroe overlooking the Chesapeake Bay. The Engineering Corps overruled her because the site was part of an artillery range and the monument would be at risk. Instead, the obelisk was located on the cemetery grounds amid the neat rows of headstones.

Work on the monument proceeded as planned and, in March 1867, the quarry notified Dix that the monument blocks would be ready to ship the following month. Before the blocks could be transported, however, she learned from the Quartermaster offices in Boston and Hampton that the movement order was repealed.

Dix travelled to Washington in May to resolve the problem and found that an ailing Meigs had asked his acting, General Daniel Rucker, to finalize the project. Rucker balked at fulfilling Meigs’ agreement to pay the $4,000 necessary to cover the transportation and construction costs. Rucker brought the issue to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton for resolution. While sympathetic to Dix’s cause, Stanton sided with Rucker. He determined that Meigs had exceeded his authority and that no government funds would be allocated.

Having exhausted the budget on a more elaborate design, Dix once again took matters into her own hands. She used her personal funds to finish the monument without bothering to seek further donations. (The government belatedly made good on Meigs’ promise and reimbursed Dix for expenses totaling $4,949 in 1872.) A crowd turned out to witness the laying of the monument cornerstone on October 3, 1867.

Installation of the capstone took place on November 28. A few weeks later, the machinery was removed and the workers departed. Although dedication of the monument would not occur until the following year, Dix’s task was complete. She had raised an enduring monument to the thousands of Union soldiers buried at the national cemetery. In later years, Union Veterans residing at the nearby Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers would, upon their passing, be laid to rest there, too, within sight of the memorial to their fallen brethren.

* A prominent Philadelphia judge suggested the quote to Dix and he probably supplied his own translation from the Greek.

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D.

Historian, National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

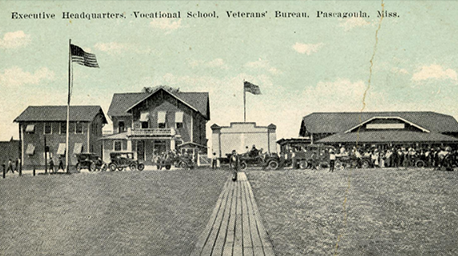

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.