Putnam Library namesake was an accomplished writer

There are some cool things about being an archivist in a history office. I get to have my hands in all the primary sources, talk about my favorite subjects, and work with researchers to find the resources they need to do their work. It’s great. One of the other wonderful things is that I am not expected to write like a historian. I get to tell stories as if I’m talking to my friends. So, friends, let’s chat about Mary Lowell Putnam, her family, finding Jane Austen in her writing, and how all that came together to impact the lives of thousands of Veterans.

March is Women’s History Month and I volunteered to write about Mary, “Benefactress of the Home”. The days were passing, and I kept asking for extensions. Why? Because most resources kept recycling the same information. When reading about Mary, one will mostly find her defined as “daughter of Unitarian minister”, “sister of James and/or Robert” and “mother of William” as if she had no personal accomplishments other than being a relation. I knew this wasn’t true, I just had to find it. So, I set out to reframe Mary Lowell Putnam.

The month is running out, but fortunately, this office does not believe that women’s history is confined Women’s History Month. Plus, our webmaster is a kind and generous sort. Did I find new things? Yes, but as so often when researching women, I had to “go through the side door” to get there. We already knew that Mary was from a wealthy Boston family, a strong abolitionist, spoke several languages, and that she lost her son early in the Civil War. What was new to write about?

For many authors, the key to who they are reside in their writings themselves. Mary tells us a lot about herself, her position in the world, and what she valued. She wasn’t content to just write, though. She acted on her convictions in ways that were not entirely usual for a woman of her time and station. That said, this was not a family afraid of unusual women. While several steps removed, her cousin John Lowell Gardner Jr, was married to Isabella Stewart Gardner, a woman most unapologetically herself. Google her, you can thank me later.

The Lowell family tree includes lawyers, historians, authors, religious leaders, military officers, presidents and faculty of Harvard, and such intelligentsia. For the space enthusiasts amongst us, the Lowell Observatory where Pluto was discovered was founded by Percival Lowell. The town of Lowell, Massachusetts, (home of Edith Norse Rogers) is named for industrialist Francis Cabot Lowell.

Mary Traill Spence Lowell was born on 3 Dec 1810 to Charles and Harriett Lowell. Gifted in languages, she was fluent in French, Italian, German, Polish, Swedish, and Hungarian, as well as being able to read and write in Greek, Hebrew, Persian, and Arabic. Some sources do vary on the list, but no matter which one uses, the list is extensive. She was also the author of no less than nine publications.

Both before and after she married, Mary spent a great deal of time traveling both the US and all over Europe, expanding her understanding of languages, political science, and culture. Though she was publishing as early as 1844, she came to public attention when she censured North American Review’s Francis Bowen. He expressed criticism of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, a stance Mary vehemently disagreed with. Bowen had lived in Paris, and one might kindly assume that he had at least visited Hungary.

Mary, however, lived in Hungary for a time, spoke the language, and published History of the Constitution of Hungary as part of her line-by-line dismantling his entire work on the matter. That wasn’t a turn of phrase; her responses to him in the Christian Examiner literally go line by line and take his arguments apart. It wasn’t the last time she used her pen to express herself.

Between 1861 and 1866, she published four books, all rooted in her abolitionist work. While she doesn’t shy away from words like “slave”, she is more delicate about it. It’s not so much dancing around the subject, it’s more like it’s hiding in plain sight. If a reader was antislavery, messaging was clear. If one was ambivalent or pro-slavery, they were just stories.

The Atlantic reviewed 1861’s Records of an Obscure Man and 1862’s Tragedy of Errors Parts I and II. It both praises and criticized the works and is not until late in the review do they note that she is a woman. My favorite part of this section is “…it is not impossible some unborn historian may write, that in certain great perils of American liberty, when the best men could only offer rhetoric, women came forward with demonstration. …that the delicacy of spirit we love to characterize by the dear word “womanly” is not inconsistent with varied and exact information, independent opinion and the insights of genius.”

Friends, if you do look up this review, please remember that it was written in May 1862 and the words and values we hold today may not be reflected in it.

By 1866, she moved on to publications where her stances on education, slavery, and a healthy dose of Jane Austen come clear. In Fifteen Days, an Extract from Edward Covil’s Journal, she writes “My farm-duties, which restrict my study-time just enough to leave it always the zest of privilege; my books, possessed or on the way…” as the sixth line, establishing early that our narrator values time with their books, a word that appears 33 times.

There are 17 instances of the word “slavery”, and 97 of the word “slave”. There were 44 in Records of an Obscure Man. “Slaveholder” does not appear in Records but 11 times in Fifteen Days. Whether this is due to the war being over or not, Mary is no longer afraid to address it head-on. She also fixes an eye towards women’s education and independence, writing “The evening she passes is sewing, a book on the table before her. She catches a line as she draws out her thread, and fixes it in her memory with the setting of the next stitch…”

The reader in question is a teacher trying to further her own education while still appearing correctly qualified for the job. She is putting one brother through college and caring for the younger two. Another character is asked to offer her a home and position as governess. His response to the idea is, “I will tell her that her cousin wishes to have news of her… But propose to her a life of dependence? You must get a bolder man to do that errand.” As I was reading this section, in my head, it sounded exactly as Sanditon’s Arthur Parker would have said. Friends, I put my cup down and went reading with a whole new eye!

Part of Jane Austen’s ability to wordsmith such compelling pictures was that she drew heavily from her own experiences. Houses she visited, things she saw in her travels, and repetition of names often made their way into Jane’s books. They underwent two resurgences, first in 1833, again in the early 1860s, and Mary would have especially read Mansfield Park. Jane stayed consistent in those themes across all her books, and Mary experimented with the same literary concept. In Fifteen Days, Harvard, Persia, Hungary, and a young man living abroad choosing his own path for a few years (as did her son) are all present. Most tellingly, though, is this line:

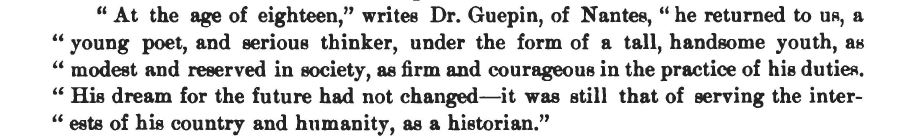

“Does Harry intend to take a profession?”

“The law, I hope. He will study it in any case. This makes part of a plan he formed for himself years ago. He considers the study of law as a branch of the study of history, and a necessary preparation for the writing of history,—his dream at present.”

There is a forward from Chaplain Earnshaw in the 1881 Putnam Library Catalog, quoting Dr. Guepin that William’s “dream for the future had not changed, it was still that of serving the interest of his country and humanity, as a historian.” I’ll discuss William and the catalog momentarily, but it is important to know here that at the time of his commissioning, William was studying law at Harvard.

This is only one line, but there are enough pattern similarities both in content and writing style for interesting study, should one choose to. It’s just not what we are doing today. “All of this is great, but how does this affect thousands of Veterans,” one is surely pondering by now. The goal was to frame Mary as herself, her accomplishments, and the momentum of her life. To not be an appendage of someone else. These are important things because had these things been different, so may have been her choices. Her most enduring decision came after the death of her son, William.

William was born 9 July 1840. When the Civil War broke out, he commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry “the Harvard Regiment” on 10 July 1861, the day after he turned 21. 103 days later, on 22 October, 1861, he died from wounds sustained at Ball’s Bluff. Accounts of William frame him as a gentle soul, a lover of literature and education. He was a poet, not a warrior, but his position in society required that he join the Army. His death framed one of the longstanding and impactful activities of Mary’s life.

As a person of wealth, power, and station, Mary had options. She could have gone to Europe to collect art and interesting people, as her cousin-in-law, the aforementioned Isabella, did after the loss of her own son. She could have shut down and taken to her bed. Both those would have been reasonable, and yet Mary did neither. She mobilized. Education and information were a critical part of Mary’s soul. I’ve not yet found any surviving documentation as to how the idea to donate books and artwork came to her attention, or why the Central Branch of the National Homes (now Dayton VA Medical Center), specifically but my hope is that it survives in the family’s collection.

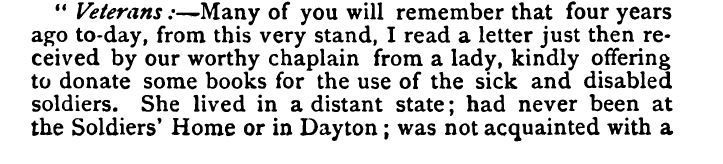

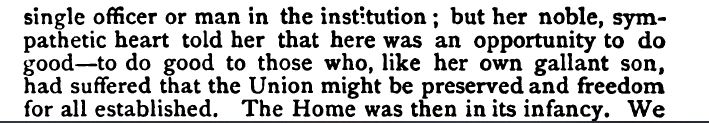

On 8 Oct 1868, Chaplain Earnshaw notified the Board of Managers that he received an offer of donation from Mary. Interestingly, the 1868 Annual Report refers to her as “Mrs. – Porter, of – “. There is no mistaking that the name is wrong. The next line states that the donation came from a lady that lost her “noble and gallant son” which is usually how William is referred to. Gobrecht’s 1875 book History of the National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, also states she had never been to the Home and was not acquainted with anyone there so that wasn’t it.

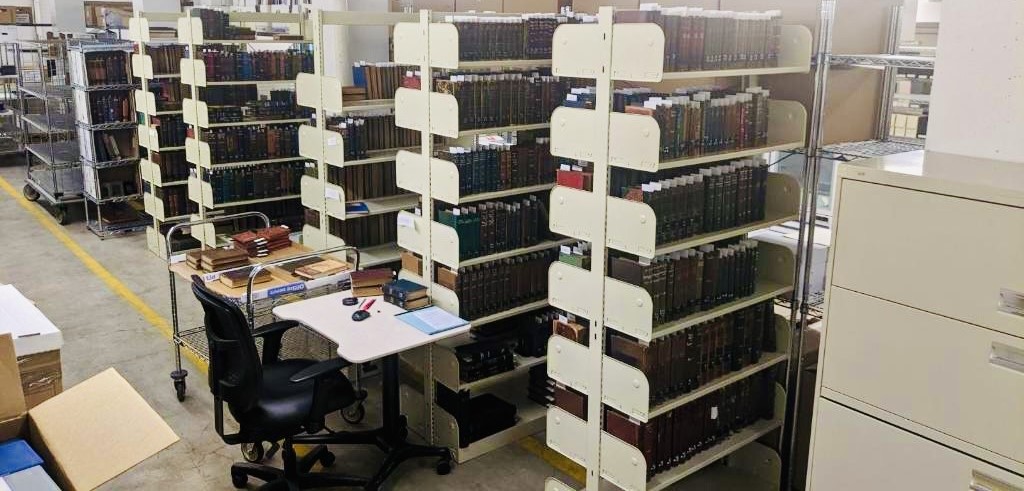

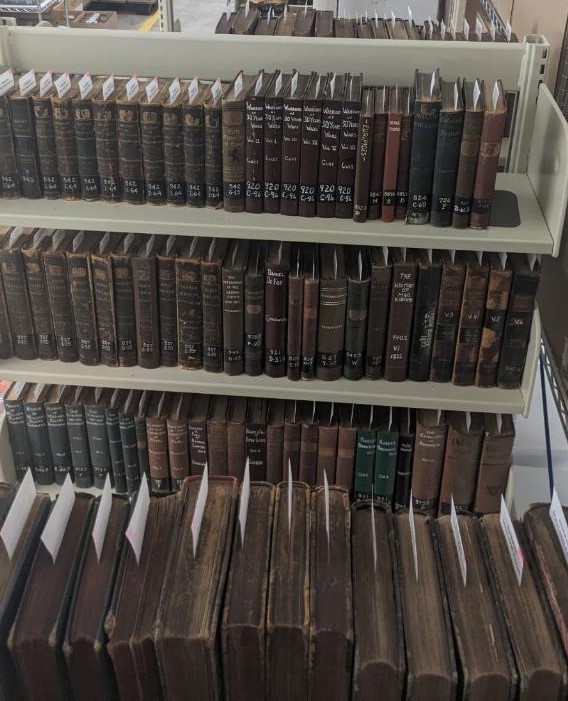

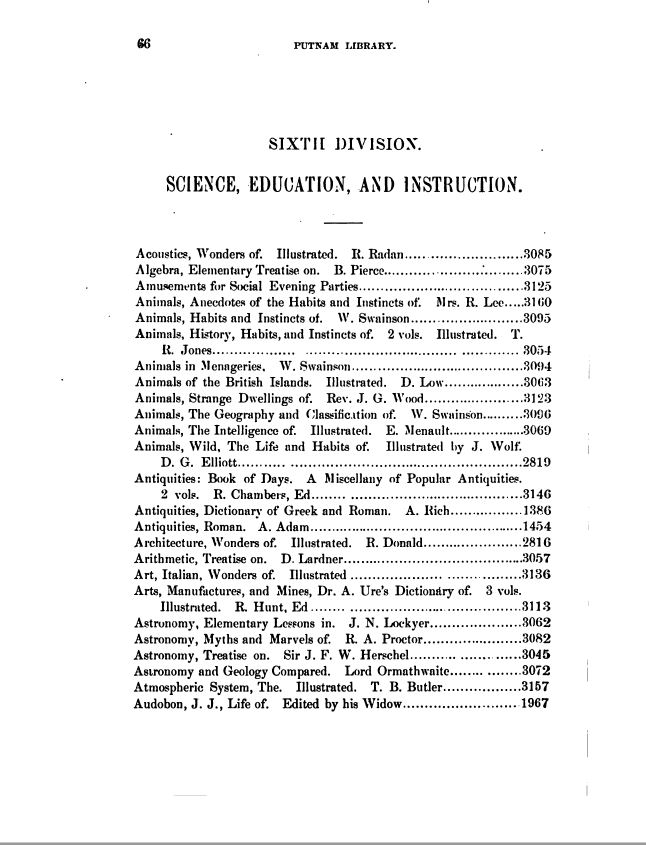

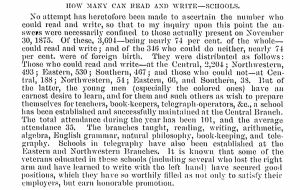

By 1881, the Putnam Library Catalog is 111 pages. Each entry is a single line, giving a straightforward look into the quantity and quality of the library’s collection. Topics include history and travels, biographies, general literature (including Mary’s own Fifteen Days and Records) novels, poetry and drama, and most importantly for this conversation, science, education, and instruction. According to the 1875 Annual Report, it was estimated that while nearly 74% of the residents of the four Homes could read and write, there were gaps in education. As such, a school, taught by one Ms. M.J. Eaton, was established at Central Branch for those wishing to learn, teaching reading, writing, arithmetic, algebra, English, philosophy, and other subjects.

This school paved the way for other training programs that prepared Veterans for work as teachers, bookkeepers, telegraph operators and printers, among other things. The 1900 census shows Paul Sandridge, a former U.S. Colored Troops member and a resident of the Home, was a teacher. While Paul was formerly enslaved, he could read and write. He furthered his education and received his teaching qualifications at the Home.

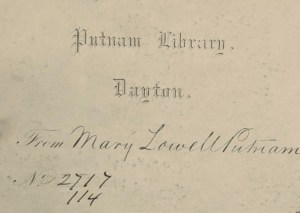

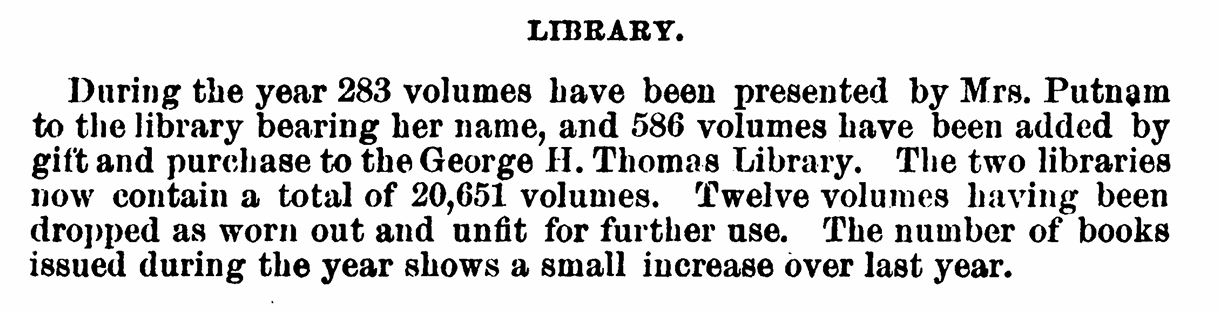

What started as a few crates turned into decades of shipments of books and artwork picked out specifically for the Home by Mary and then later her daughter Georgiana. How do we know that Mary and Georgiana selected the volumes themselves? Their signed bookplates were on the inside covers of every book they donated. In 1897, the Annual Report states that Mary had donated 283 volumes that year. Between the Putnam and Thomas libraries, the collection contained 20,651 volumes. Were the books used? Yes, according to that same report, there were 46,798 books read. By the 1900 report, Georgiana’s donations were down to 73 volumes, but were 11,041 books in the Putnam Library.

Mary died 1 June 1898, but her legacy remains active at the National VA History Center. While the Putnam Library building is closed for now, we still have approximately 2000 of the books that she donated. It might be thought, by some, that this is a tragic loss. I think otherwise.

The reason that we don’t have more of the books left is because they were used, repaired, and used until they were no longer serviceable and had to be discarded. Decades of Veterans engaged with the books Mary provided. That is exactly what she wanted. It is a truth universally acknowledged that education has the power to change lives. Many times, that door must be opened before someone may walk through. For Veterans at the Central Branch of the National Homes, and subsequently the VA, that person was Mary Lowell Putnam.

By Robyn Rodgers

Senior Archivist, National VA History Center

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

The Story Behind the National Homes’ Seal

The National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers turns 160 years old in 2025. The campuses are the oldest in the VA system, providing healthcare to Veterans to this day.

At the time of their establishment, they were the first of their type on this scale in the world. Within the NHDVS seal is the story that goes back 160 years ago.

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? Fire Safety and Prevention at the National Homes

Fire safety may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about Veteran care, but during the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers period (1865-1930), it was a critical concern. With campuses largely constructed of wooden-frame buildings, housing thousands of often elderly and disabled Veterans, the risk of fire was ever-present. Leaders of the National Homes were keenly aware of this danger, as reflected in their efforts to establish early fire safety protocols.

Throughout the late 19th century, the National Homes developed fire departments that were often staffed by Veteran residents, and the Central Branch in Dayton even had a steam fire engine. Maps from this era, produced by the Sanborn Map Company for fire insurance purposes, reveal detailed records of fire prevention equipment and strategies used at the Homes. These records provide us with a rare glimpse into evolving fire safety measures in the late 19th and early 20th Century, all part of a collective effort to ensure the well-being of the many Veterans living there.

Curator Corner

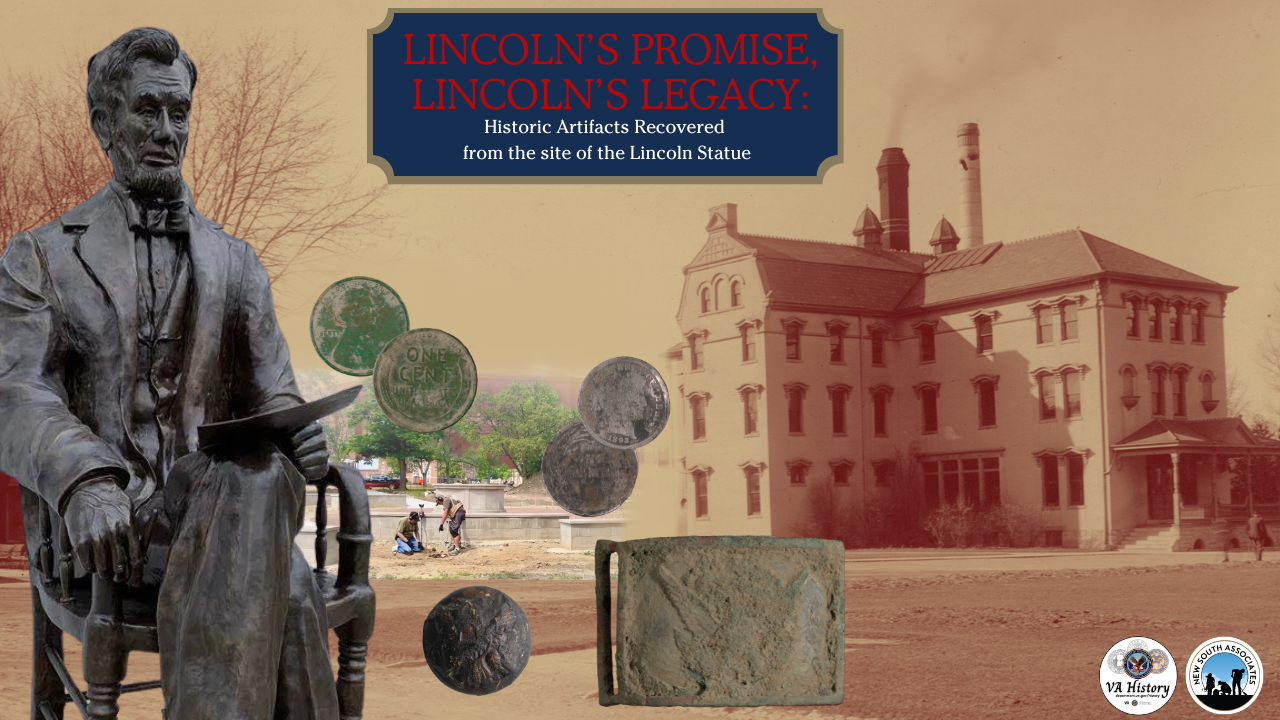

Lincoln’s Promise, Lincoln’s Legacy: Historic Artifacts Recovered from Site of Dayton Statue

It all started when Bill DeFries, President of the American Veteran’s Heritage Center (AVHC), lost his wedding ring at the construction site for the statue of Abraham Lincoln on the campus of the Dayton VA Medical Center. He requested the assistance of the Dayton Diggers, a local nonprofit whose mission is to “research, recover, and document history” through their use of metal detector survey. The machines used by Dayton Diggers emit an electromagnetic field that responds to metal objects hidden below the ground surface. When they pinpoint a target, they use minimally invasive excavation to remove the object from the soil. In addition to the misplaced wedding band, their team uncovered historic artifacts that can be used to understand the history of Veteran care here in Dayton.