After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Since the time of the American Revolution, Veterans seeking compensation for a wartime injury had to furnish documentation, typically in the form of affidavits, establishing the link between their military service and their disability. Meeting the burden of proof could be difficult under any circumstances. It was especially challenging for Great War Veterans who contracted tuberculosis or developed some sort of neuropsychological problem.

The two conditions were commonplace during the war years. They accounted for an estimated one-third of the more than 300,000 medical discharges from the Army between 1917 and 1919. These maladies were also responsible for about two-thirds of the hospitalizations of military men after the war. Yet, claimants with tuberculosis or mental disturbances still struggled to make their case to the Bureau of War Risk Insurance. In some instances, the problem was that they showed no signs of the disease until after their release from service. In other instances, they failed to provide sufficient evidence tying their illness to their time in uniform.

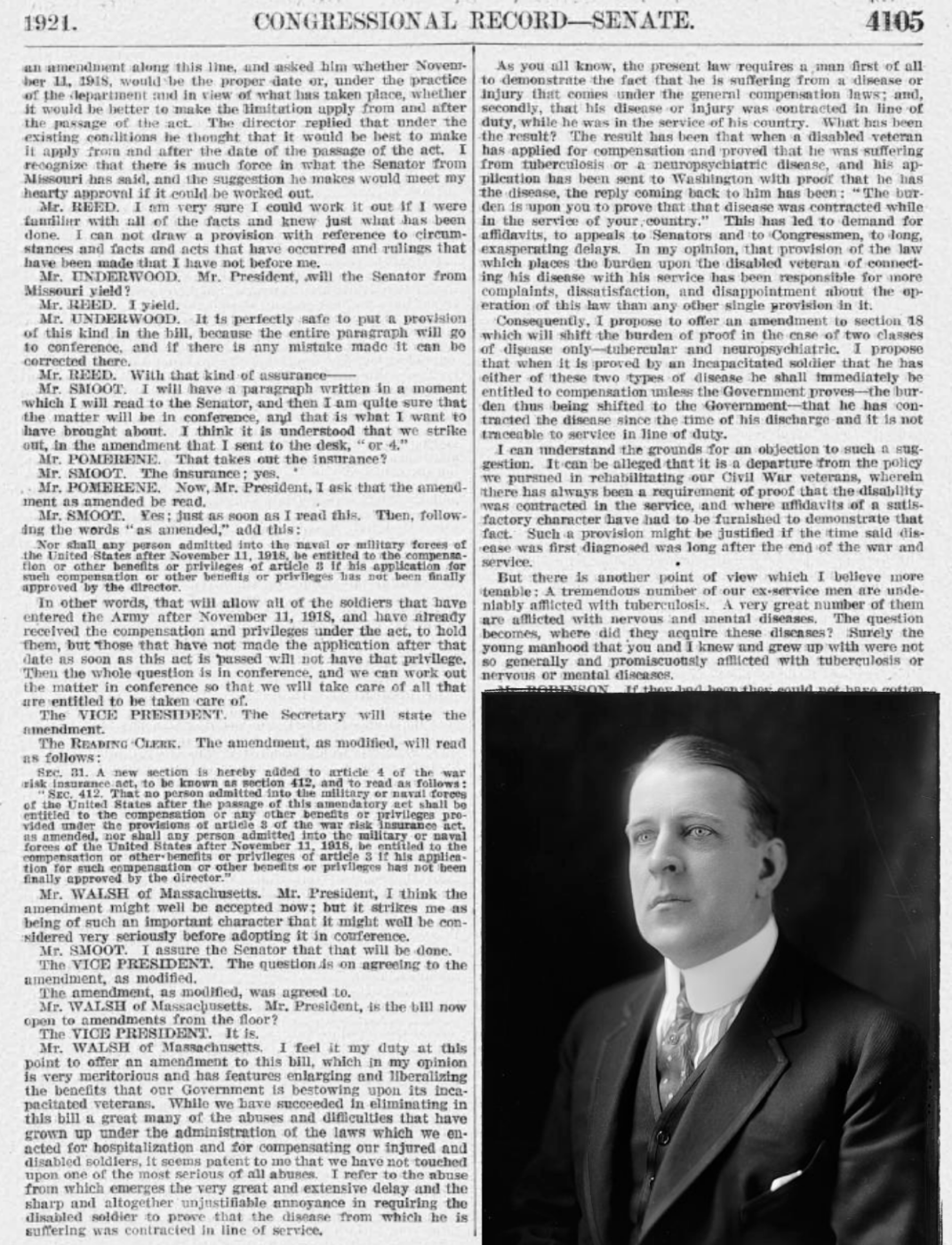

Their plight caught the attention of Massachusetts Senator David I. Walsh. By early 1921, Veterans organizations, the press, and politicians from both parties had all concluded that the federal government was falling short in its efforts to serve disabled Veterans. In the spring, Congress decided to act. The House approved a sweeping plan backed by the American Legion to replace the Bureau of War Risk Insurance with a new agency that would be responsible for all benefit programs for World War I Veterans, from compensation and insurance to vocational training and medical care.

In the Senate, Walsh headed a special committee that conducted hearings and collected data on the treatment of disabled soldiers in preparation for a vote on the House bill. In late July, when the Senate as a whole convened to debate the bill, Walsh stood up from his chair to offer an amendment that would bring relief to “the tremendous number of our ex-service men [who] are undeniably afflicted with tuberculosis . . . [or] nervous and mental diseases.”

Over and over again, he explained, he had heard anguished complaints from “men who have these diseases, know they have them, have had it demonstrated by doctors that they have them, and then have the Government say to them, ‘Prove it, prove it, prove that you have the disease as a result of your service.’”

The remedy Walsh proposed was to remove the burden of proof from the claimant. “My amendment would raise a presumption at once that as he has one of the aforesaid diseases he must have contracted it in line of service.” While this represented a major departure from more than a century of statutory practice governing wartime disabilities, Walsh emphasized to his fellow senators that the exception only applied to two specific categories of medical complaints.

After a brief discussion, the measure was approved and incorporated into the bill. The Senate completed its work on the legislation soon after and the act establishing the Veterans Bureau to oversee all benefits for Great War Veterans became law on August 9, 1921. In its final form, Walsh’s amendment granted a presumption of service connection to anyone diagnosed with tuberculosis or a neuropsychiatric disease within two years of separation from military service. Eleven months after the Veterans Bureau began applying the new rules for claims, over 57,000 tuberculosis sufferers and mental health cases were receiving a monthly check for their condition.

Although limited at first to two types of disabilities, the 1921 act also authorized the head of the Veterans Bureau to make any rules and regulations necessary to carry out the provisions of the law, thus opening the door to more exceptions. Sure enough, before the end of the year, the Veterans Bureau had granted presumptive status to diabetes, leukemia, rickets, and other ailments classified as chronic constitutional diseases that became manifest within a year of discharge. The presumptive list continued to grow under the Veterans Administration, which replaced the Veterans Bureau in 1930.

After World War II, VA used its regulatory powers to establish a new category of presumptions, tropical diseases. By 1957, when Congress codified all benefits laws, VA recognized 40 chronic and 17 tropical diseases as presumptive. In the 1970s and 1980s, Congress applied the presumptive label to a range of diseases and disorders affecting former prisoners of war. In more recent years, a series of landmark laws starting with the Agent Orange Act in 1991 and culminating in the 2022 PACT Act have extended the presumption of service connection to Veterans with health conditions arising from their exposure to toxic substances and environmental hazards.

By Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D.

Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

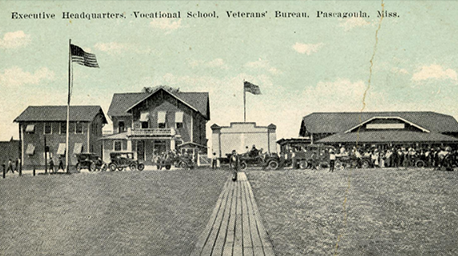

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.