A lucky few National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS) branches were intended to display elegant stained-glass windows of Civil War heroes, artifacts from temporary commemorative arches built for the Grand Army of the Republic’s (GAR) 21st Annual Encampment in September 1887 in St Louis, Missouri. The oversized windows — called “cathedral glass” or “transparencies,” and incorporated into state-of-the-art “illuminations” at the gathering – are as fascinating as components of a technology-driven display as they are for their artistic beauty. After sunset, electric lights would bring the images of President Abraham Lincoln and General Ulysses S. Grant to life for onlookers in the streets below, in the way that neon and Jumbotrons would have first awed twentieth-century audiences.

Of four windows proposed, only two are known to survive. The only one currently on exhibit is of President Lincoln at the VA Eastern Kansas Health Care System – Dwight D. Eisenhower VA Medical Center in Leavenworth, Kansas (former Western Branch NHDVS). The Lincoln memorial window had been in the “new” Queen Anne-style Ward Memorial Hall (Building 29) built in 1888; it was likely removed in the early 1990s for restoration before being reinstalled in a new domiciliary (Building 160).

The other window, of General Ulysses S. Grant in an equestrian pose, is in storage at the Clement J. Zablocki Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (former Northwestern Branch NHDVS). It had been installed in the Victorian Ward Memorial Hall (Building 41) built 1881. Long-obscured by interior alterations to the theater, around 2017 the glass panels were dismantled and secured. They await restoration funding and a new location for reinstallation.

GAR posts have a history of creating resplendent memorial windows. GAR was an influential Union Veterans’ organization that lobbied for legislation, care and education of Civil War Veterans’ orphans and widows, and more. Annual national encampments attracted Veterans and visitors alike from 1866 to 1949; besides GAR business, local tours, dinners, music, memorial events and the parade punctuated the gatherings.

The 1887 GAR encampment in St. Louis, held September 26-30, drew an estimated 30,000 veterans. The GAR plans benefited from the city’s annual “illumination” fest in which electric and gas lights festooned streets in the business district, exploiting recent urban street-lighting improvements. It reportedly incorporated 48,000 linear feet of lighting using 50,000 colored globes fed by gas pipelines as well as extensive electric lights.

City and GAR committees coordinated on the design of four arches built over major streets for the encampment. Two contained the Lincoln and Grant images. “It was suggested that statues of [Winfield S.] Hancock and [James] Garfield be placed at other points” in the city, but these may have been passed over for a locomotive and eagle. Newspaper coverage described the final installations and impressions, however.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper reported, the “vast fiery arches…are novelties which may well attract admiring attention. Two of them enshrine colossal illuminated portraits of Grant and Lincoln.” The industrial-style Lincoln arch at Broadway and Washington streets, 40 feet tall, is “a double arch braced by cross-pieces of piping. The sides and all the cross-pieces of the arch are set with burners, in close succession, each shaded by a colored globe… On top of the arch rests a huge transparency of colored cathedral glass… With the transparency will be powerful electric arc lights which will render the picture easily distinguishable half a mile away.”

The pose captured in the Lincoln window, which measures 15 feet tall by 7 feet wide, is based on an 1871 memorial sculpture located in the U.S. Capitol carved by Vinnie Ream, the first female artist commissioned to create a work of art for the federal government. The French Silvering and Ornamental Glass Company of St. Louis produced both “transparencies.” The Brush Electric Association, responsible for the lighting system, had to insulate its wiring so the arch would not impact service to its customers.

Grant was a fixture on the most prominent, triumphal, arch in “a transparency of cathedral glass 15 feet square. Like the Lincoln transparency, the Grant transparency will be illuminated from within by electric lights.”

The Noxon, Albert & Toomey company built the Grant arch as a wooden shell “covered with muslin and the color design…applied in oil paints” to look like stone. It “elicited the greatest praise from all,” reported the St. Louis Dispatch, “especially the veterans, who were delighted with it. The ‘Old Commanders’ familiar figure was seen mounted on horseback with a spy-glass in his hand and a look of countenance, as if he were surveying a battle-field. The picture is made in richly-colored glass, and under the glare of the lights the effect was beautiful.”

Following the encampment, the GAR Illumination Committee described the “pictures of cathedral glass…a complete failure,” but does not explain why. Possibly it was associated with downpouring rain that besieged many activities. Closure for the event included, in December 1887, the GAR’s provision of the windows to permanent facilities for veterans’ future enjoyment: “Four very large Cathedral glass transparencies” were prepared for “setting as memorial windows…sent one to each of the national Soldiers’ Homes at Dayton, Milwaukee, Hampton and Leavenworth, Ks.” Well, almost permanent. The restored Lincoln window resides not far from Ward Memorial Hall, but 134 years after looking down from a triumphal arch, General Grant is still looking for its forever home.

Sources

- Multiple articles in the St. Louis Dispatch and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly from August to December 1887, Newspapers.com

- Historic American Buildings Survey, Northwestern Branch-National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers

- Architect of the Capitol

By Sara Amy Leach

Senior Historian National Cemetery Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

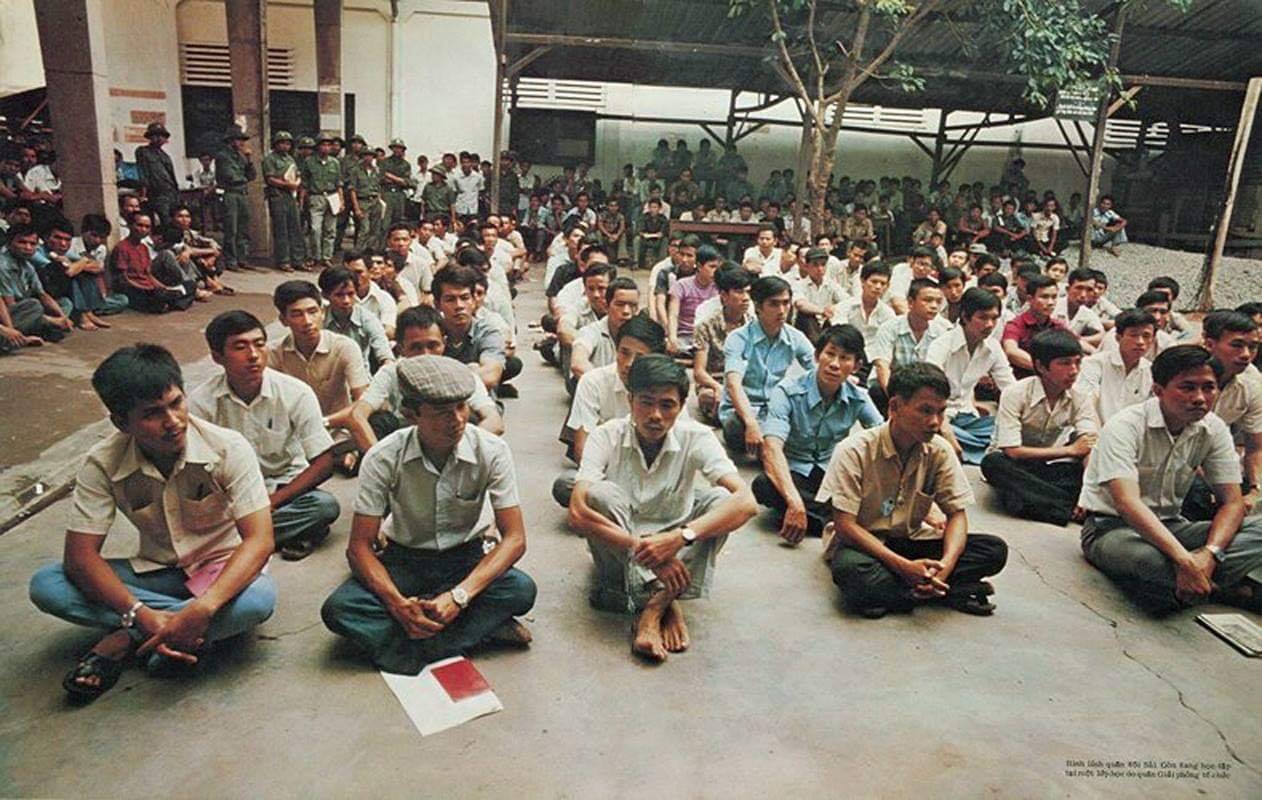

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."

Featured Stories

History of Former Whipple VA Directors Schmoll And McIntyre

Leadership change is something that happens constantly, whether it’s due to promotion, health, or other circumstances. At the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Northern Arizona Medical Center (formally known as Whipple VA Hospital) in Prescott, Arizona, directors have stayed in their position on average, three to five years. The shortest stint was 22 months, the longest was 16 years and two months. Most former directors moved on and retired elsewhere. However, two former directors, Paul N. Schmoll and Virgil I. McIntyre, either returned to or stayed in Prescott following their retirement. Both men are laid to rest at local cemeteries in the Prescott, Arizona, area.