The National Homes: Serving all who served for 160 years

Few American innovations have had an impact like the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Picture it: You return home forever changed by the experience of service. Maybe you were a farmer or a shoemaker before the war, but now you’ve lost a limb or have a disability that keeps you from going back to the life you had before.

The challenges of returning to farm or factory jobs meant that many disabled Union Veterans couldn’t make a living as before. This even meant some Veterans were at risk of unemployment and homelessness. You may think these are modern issues, but these are problems every generation has faced.

Before the Civil War, there were places for “Regulars” (career soldiers) to receive care after their service. But there had never been a facility in any country dedicated to all who served. During the war, the Army’s medical department couldn’t keep up with the large number of “Volunteers.” So civilian institutions like the United States Sanitary Commission helped fill the gaps. These civilian volunteers, like Delphine P. Baker, advocated and raised money for volunteer soldiers. After the war, she started a petition for Congress to build a national system to care for Veterans.

Senator Henry Wilson introduced a bill just days before Congress adjourned in 1865 and it passed speedily and with great support. On March 3, 1865, exactly one day before his famous Second Inaugural Address, President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law. The act officially created the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. These homes were the real-life example of Lincoln’s promise to care for those who bore the battle and the result of all the civilian efforts to support the Union during the war. It paved a road for the American people to serve the heroes who fought to end slavery and restore the Union.

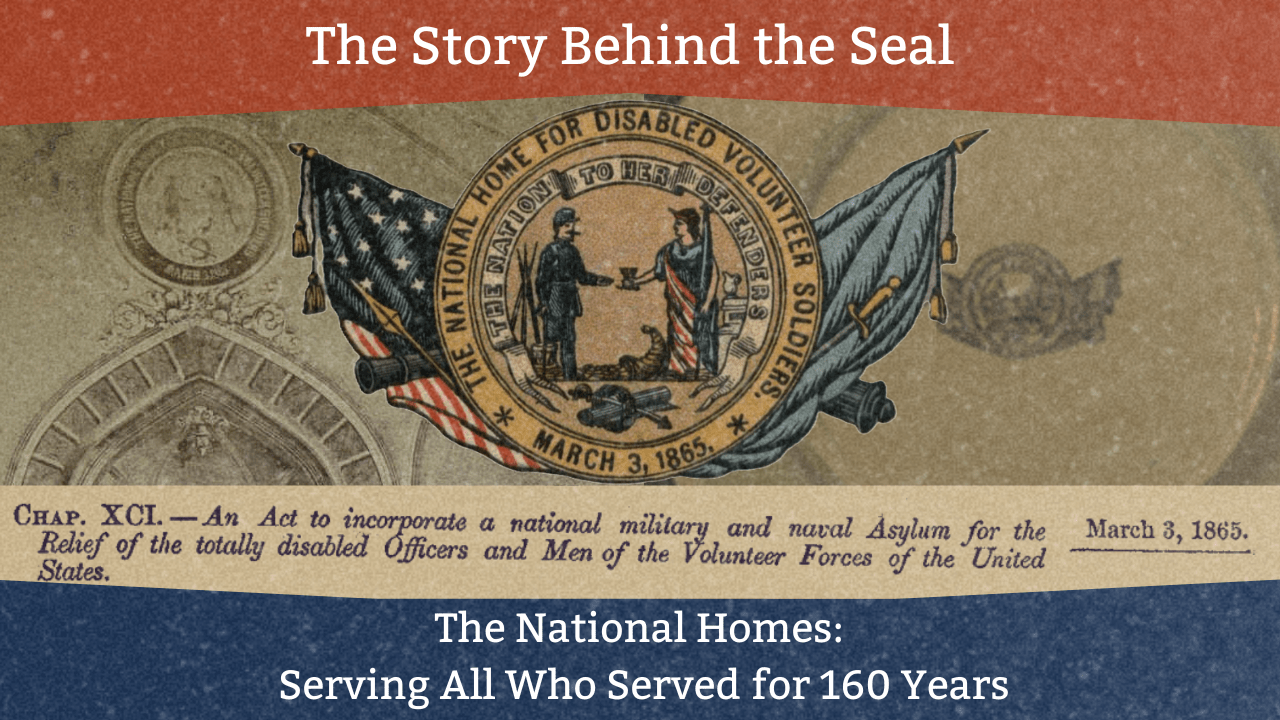

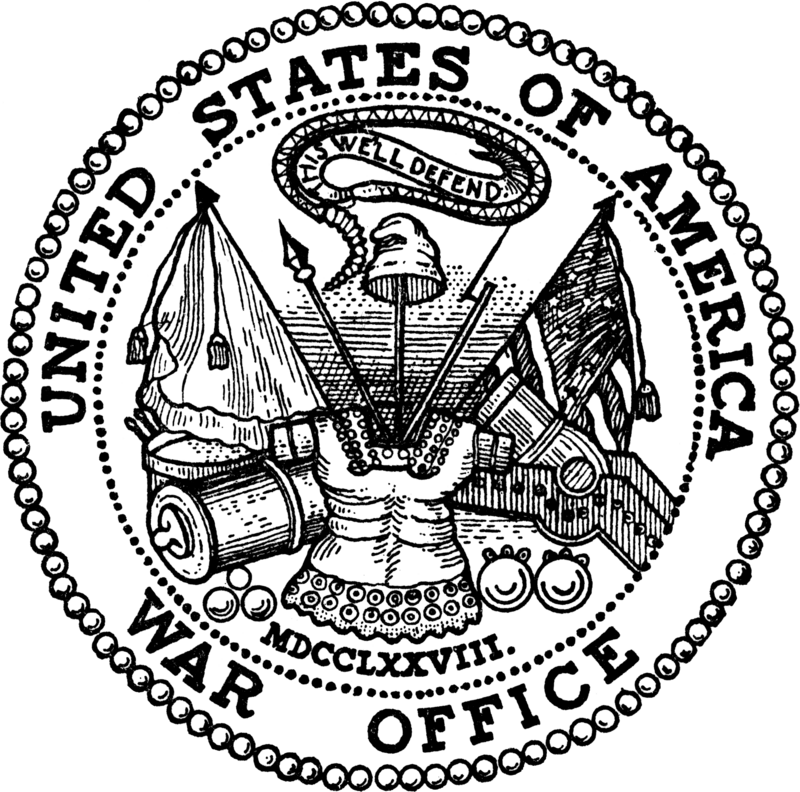

For the 160th anniversary, lets examine the symbolism of the National Home’s official seal.

Most people are familiar with these kinds of emblems; the President has an official seal, each branch of the Armed Forces has their own, as do Federal Agencies, including VA.

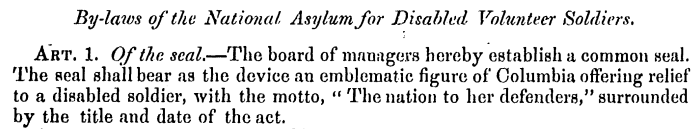

In 1866, the National Home wrote a set of rules for the organization to follow. The first rule stated, “the seal shall bear as the device an emblematic figure of Columbia offering relief to a disabled soldier.” The final design contains many elements that strengthen its meaning. It is used at the beginning of reports written by the board of managers and is featured prominently in buildings across the National Homes.

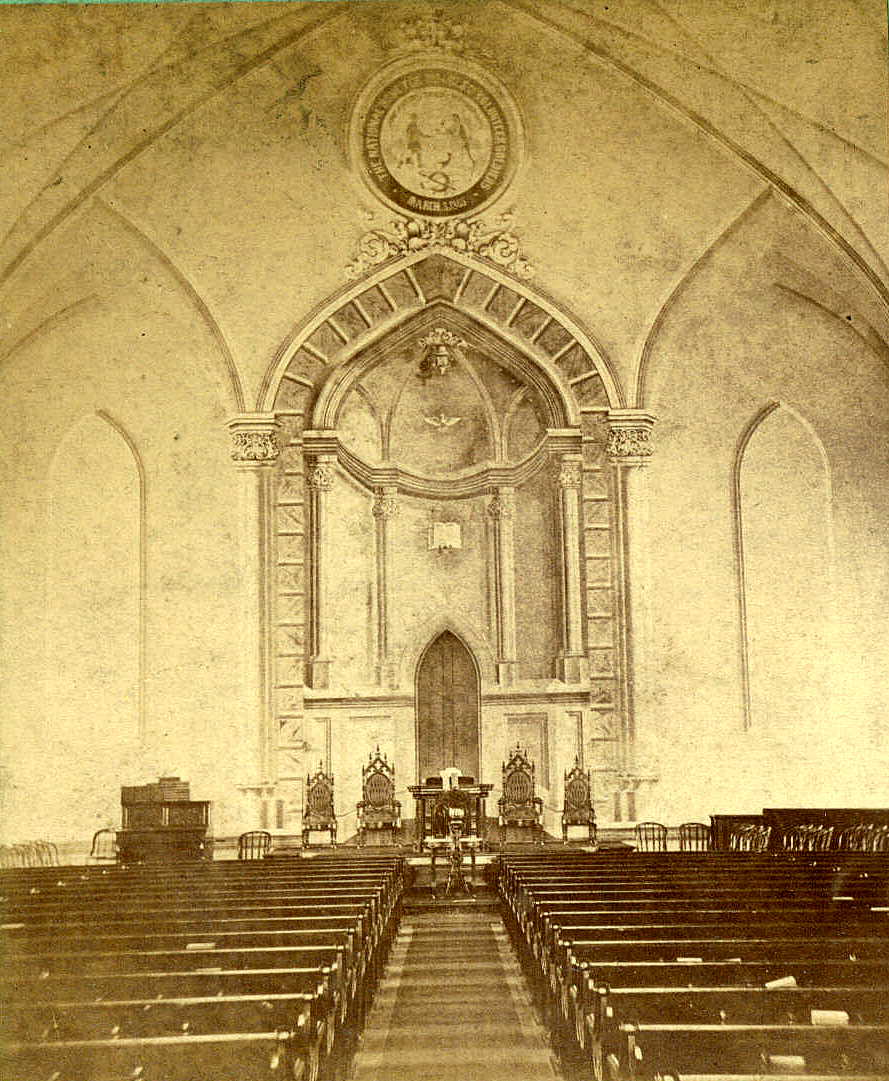

The branch located in Dayton, Ohio was the headquarters for the organization and contains some of the oldest buildings in VA’s system. The Veterans who built the Home Chapel included a giant version of the seal in the front of their church. On a smaller scale, the seal was stamped on every ceramic dish and bowl used in the Homes’ mess halls. The seal makes it easy for archaeologists to identify dishware that was used at the National Homes. Many examples of dishware featuring the seal can be found in the National VA History Center’s collections.

So, what’s on this seal? The figure on the right side is Columbia, a mascot-in-human form of the U.S. in the early days of our history. Think of her like the older sister of Lady Liberty, who represents the ideals of freedom and liberty. On the National Home seal, Columbia is depicted like a goddess figure. She wears Greek and Roman inspired robes and clutches the national colors close to her. She wears a tiara and holds out a cup to the center.

Behind Columbia is an object that resembles a casket or sarcophagus. On top of this object sits a pitcher, which may represent the contents of it were achieved only through the ultimate sacrifice for one’s nation. Pitchers are used to serve others, so it could symbolize that even after death, one’s service to their nation is remembered. Columbia’s offer of the cup symbolizes the nation offering its service to the Veteran.

On the other side, a disabled Union soldier whose leg has been amputated stands holding a cane in one hand and the other is reaching out towards Columbia. Behind him sits a “stack” of rifles. The call to stack arms is done when a company is stopping to rest. This may have communicated that even though the Veteran’s war service was over, they are still ready and willing to defend the nation.

Next to the Veteran is a snare drum, which is borrowed from the official seal of the United States Department of the Army. According to the Institute of Heraldry, the drum represents “public notification of the Army’s purpose and intent to serve the nation and its people.” Behind the seal are more elements inspired by the “War Office Seal” used by the Army between 1778 and 1947 prior to the establishment of the Department of Defense, which had two flags accompanied by a sword, a spear, and cannons, symbols of the army.

Between the two figures sits a cornucopia, a symbol of abundance. In the front, a bundle of sticks called fasces and a cavalry sword are wreathed with laurels. The fasces is an ancient symbol representing unity and authority and the cavalry sword still serves as a symbol for the Union Army. Laurel wreaths symbolize victory, so all together they can represent the Union’s total military and political victory over in the war.

The official seal shows the Nation’s promise of abundance and service to the people who defended her. The National Homes represent not just the earliest ancestor of the modern VA, but a major shift in how the country understood the volunteer soldier. Instead of the American people paying back the Veteran, they are reaching out to share the abundance guaranteed by their wartime sacrifice. It represents what VA is all about at its core, a 160-year legacy of civil servants reaching out in service to all those who served them.

By Gage Huey

Museum Collections Manager, National VA History Center

Share this story

Related Stories

Curator Corner

What’s in the Box? Fire Safety and Prevention at the National Homes

Fire safety may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about Veteran care, but during the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers period (1865-1930), it was a critical concern. With campuses largely constructed of wooden-frame buildings, housing thousands of often elderly and disabled Veterans, the risk of fire was ever-present. Leaders of the National Homes were keenly aware of this danger, as reflected in their efforts to establish early fire safety protocols.

Throughout the late 19th century, the National Homes developed fire departments that were often staffed by Veteran residents, and the Central Branch in Dayton even had a steam fire engine. Maps from this era, produced by the Sanborn Map Company for fire insurance purposes, reveal detailed records of fire prevention equipment and strategies used at the Homes. These records provide us with a rare glimpse into evolving fire safety measures in the late 19th and early 20th Century, all part of a collective effort to ensure the well-being of the many Veterans living there.

Curator Corner

Lincoln’s Promise, Lincoln’s Legacy: Historic Artifacts Recovered from Site of Dayton Statue

It all started when Bill DeFries, President of the American Veteran’s Heritage Center (AVHC), lost his wedding ring at the construction site for the statue of Abraham Lincoln on the campus of the Dayton VA Medical Center. He requested the assistance of the Dayton Diggers, a local nonprofit whose mission is to “research, recover, and document history” through their use of metal detector survey. The machines used by Dayton Diggers emit an electromagnetic field that responds to metal objects hidden below the ground surface. When they pinpoint a target, they use minimally invasive excavation to remove the object from the soil. In addition to the misplaced wedding band, their team uncovered historic artifacts that can be used to understand the history of Veteran care here in Dayton.