History of VA in 100 Objects

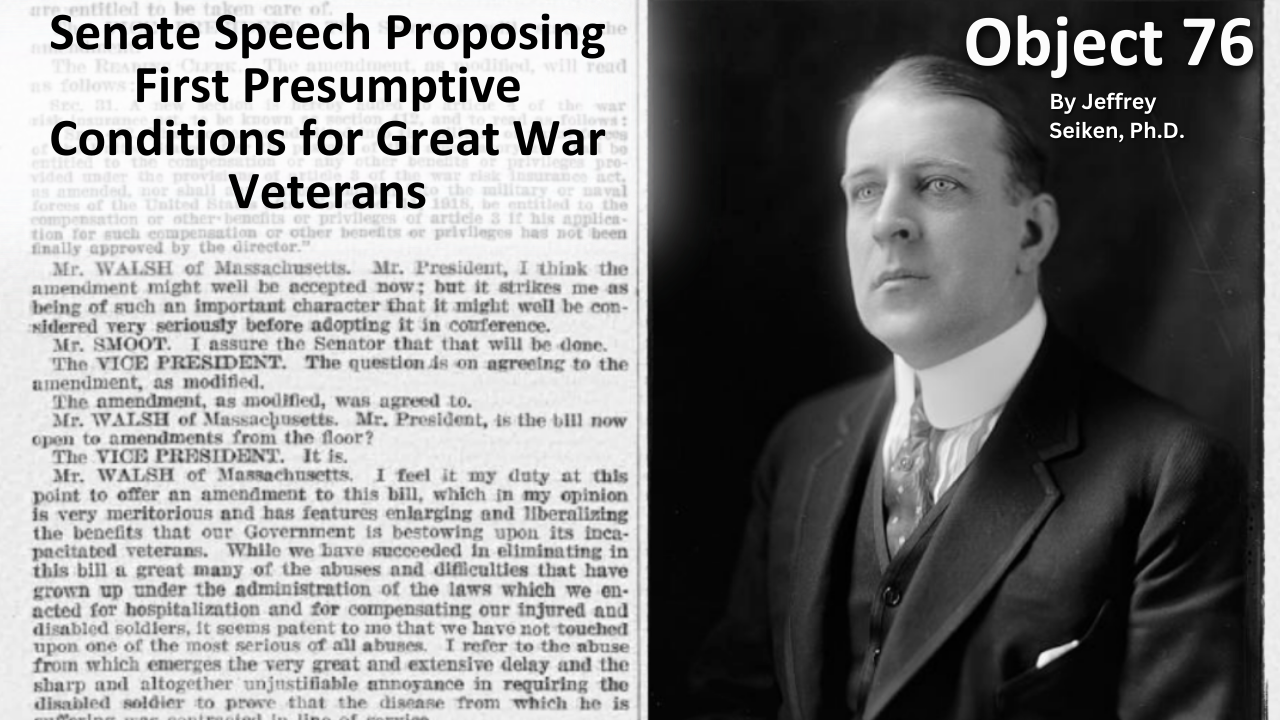

Object 76: Senate Speech Proposing First Presumptive Conditions For Great War Veterans

After World War I, claims for disability from discharged soldiers poured into the offices of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the federal agency responsible for evaluating them. By mid-1921, the bureau had awarded some amount of compensation to 337,000 Veterans. But another 258,000 had been denied benefits. Some of the men turned away were suffering from tuberculosis or neuropsychiatric disorders. These Veterans were often rebuffed not because bureau officials doubted the validity or seriousness of their ailments, but for a different reason: they could not prove their conditions were service connected.

Due to the delayed nature of the diseases, which could appear after service was completed, Massachusetts Senator David Walsh and VSOs pursued legislation to assist Veterans with their claims. Eventually this led to the first presumptive conditions for Veteran benefits.

Curator Corner

Reframing Mary Lowell Putnam

Mary Lowell Putnam is tied to VA history by her generous donation of a large volume of books to the Central Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. These books, meant to honor her son who died in the Civil War, helped foster reading advancement for the Veterans who lived there after the war and into the 20th Century. However, her life was more than just a moment in time donating books. It included a life-long study of languages and a very sharp opinion that she shared in writing throughout her life.

Exhibits

New Skills, New Freedoms: Occupational Therapy Artifacts from the National VA History Center

While Veterans engaged in activities and learned trades at the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS) since its inception after the Civil War, formal occupational therapy programs became components of rehabilitative care for Veterans beginning in the 20th century. This exhibit explores what type of activities were used to treat Veterans by showing items from the collection at the National VA History Center.

History of VA in 100 Objects

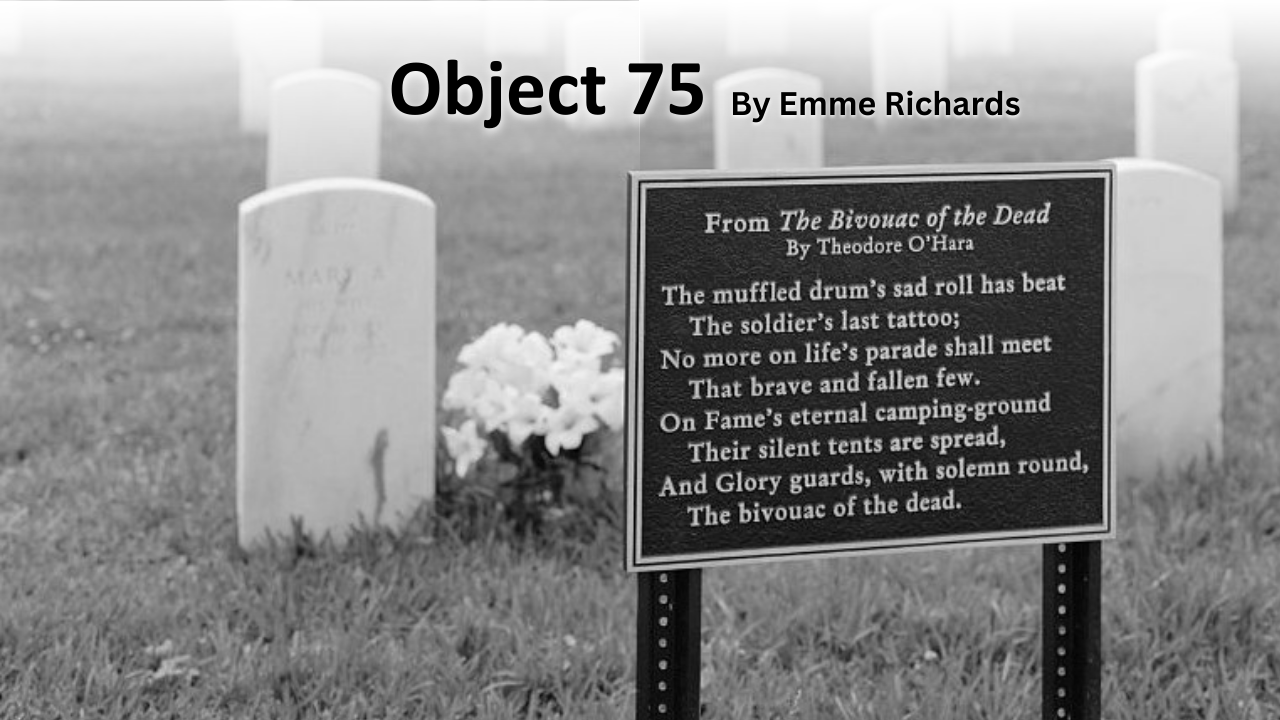

Object 75: “Bivouac of the Dead” Tablet

The mounted plaque stands in front of the headstones at Mobile National Cemetery in Alabama. The dark, cast-aluminum tablet draws a stark contrast to the sea of pearly marble beyond. Across its face in white lettering runs the sorrowful first stanza of Theodore O’Hara’ elegiac poem, “Bivouac of the Dead,” beginning with the verse “The muffled drum’s sad roll has beat / The Soldier’s last tattoo; / No more on life's parade shall meet / That brave and fallen few.” Tablets bearing passages from O’Hara’s poem can be found in dozens of VA national cemeteries across the country. Originally written to honor the Kentucky volunteers who died in the Mexican War (1846-48), the poem now serves as a literary memorial to all lives lost in service to the nation.

Curator Corner

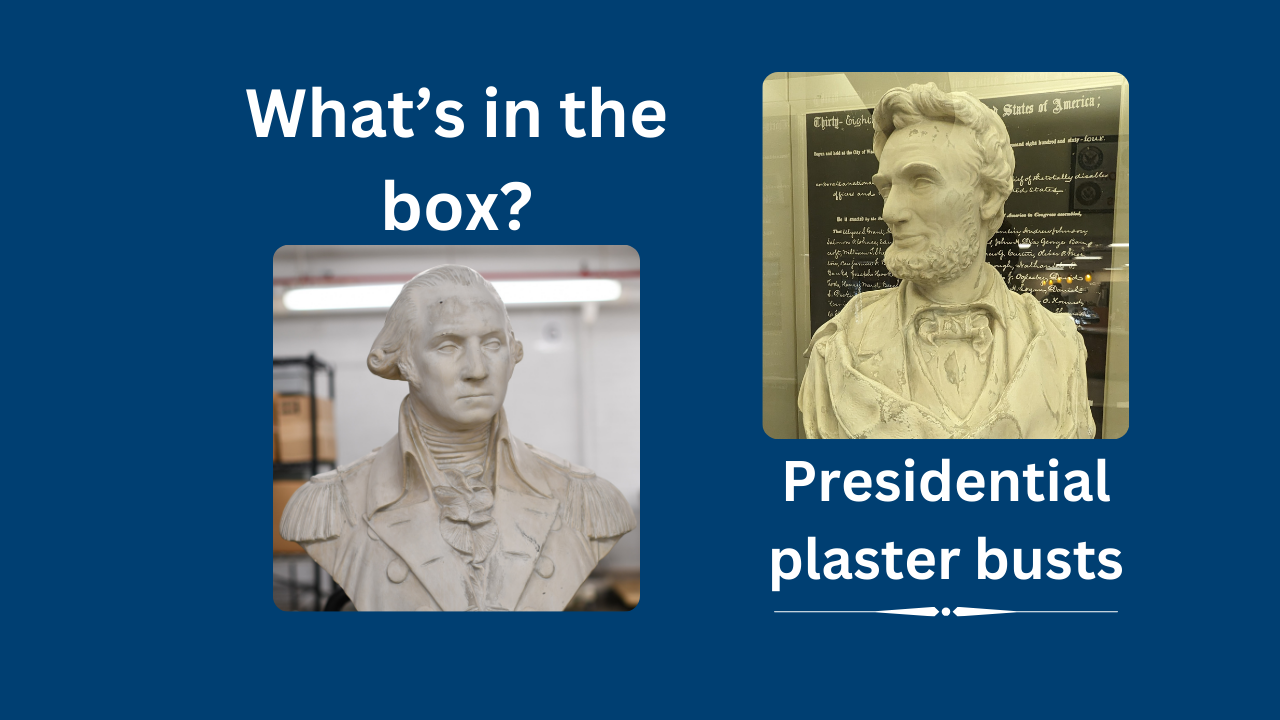

What’s in the Box? A Pair of Plaster Presidential Busts

Presidents George Washington and Abraham Lincoln are among the most easily recognizable figures in American history. Their faces are symbols of wisdom, strength, and leadership. Even today, polls consistently rank them as the greatest or most successful presidents. With that in mind, it is unsurprising that the appreciation of these legendary statesmen has deep historic roots. In honor of their birthdays, our team at the National VA History Center explored those roots through this pair of plaster busts.

History of VA in 100 Objects

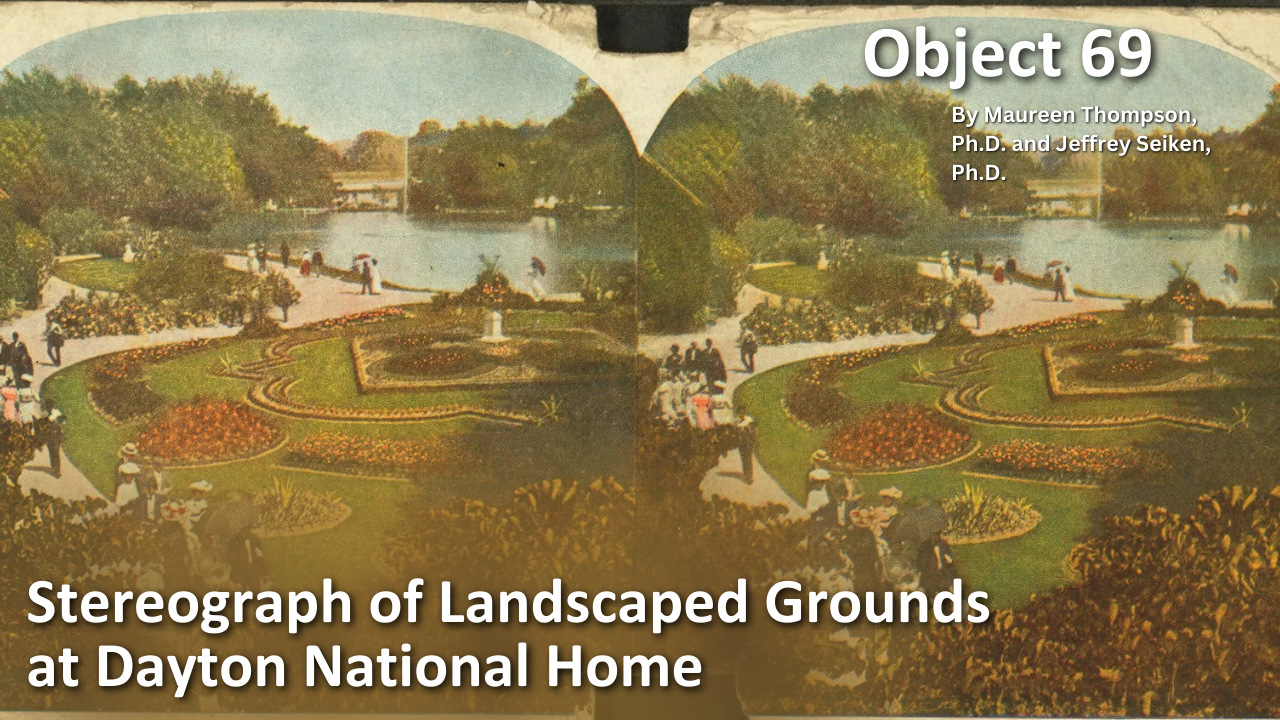

Object 69: Stereograph of Landscaped Grounds at Dayton National Home

The federal government in the Civil War arranged to care for returning soldiers too weakened by their wounds, the lingering effects of disease, or the hardships of military life. In the decades after the war, the government established the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

The Board of Managers for the National Home added such amenities as chapels, libraries, theaters, and playing fields. Great care also went into the shaping of the physical environment. The board employed landscaping architects to design the grounds of each branch to create an attractive, idyllic setting for residents and visitors alike. Influenced by the picturesque landscape movement, they adorned the National Home campuses with man-made ponds and lakes, ornate flower gardens, elaborate plantings of shrubs and trees, winding trails, and other features to beautify the properties.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 65: Civil War 6×6 Unknown Grave Markers

Graves of unknown soldiers in the national cemeteries are commonplace and marked in many different ways. While the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in the Army’s Arlington National Cemetery is the most culturally recognizable unknown grave, VA national cemeteries also have less grand examples of unknown burials that span the early 19th century through the Korean War. The most common form of unknown marker, however, is the simple 6x6-inch stone that adorns the graves of thousands of Civil War soldiers.

History of VA in 100 Objects

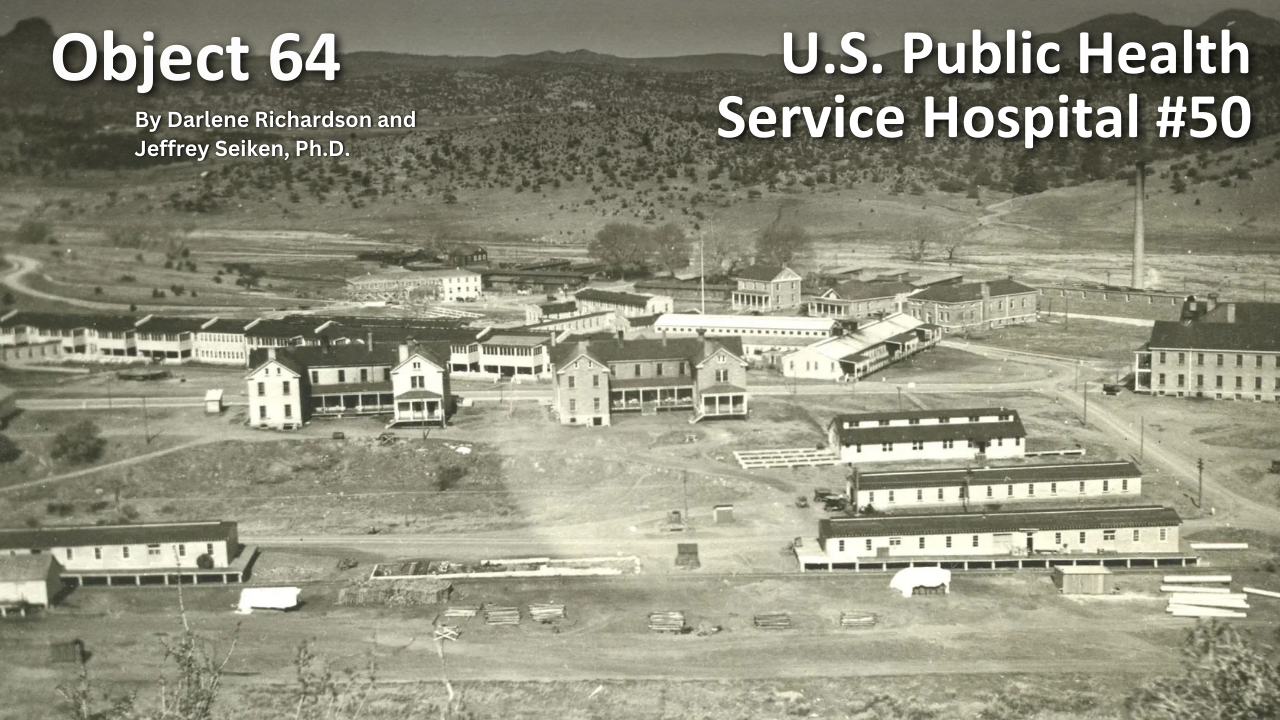

Object 64: U.S. Public Health Service Hospital #50

U.S. participation in the First World War produced a shift away from relying on long-term institutional care for Veterans in need to a model of Veteran welfare centered around short-term hospitalization. During the war, the War Department assumed responsibility for tending to the sick and wounded. Afterwards, when the Army dismantled its hospital system, the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) stepped in to fill the breach, acquiring numerous facilities the Army and Navy no longer wanted as well as other properties that could be used for medical purposes.

History of VA in 100 Objects

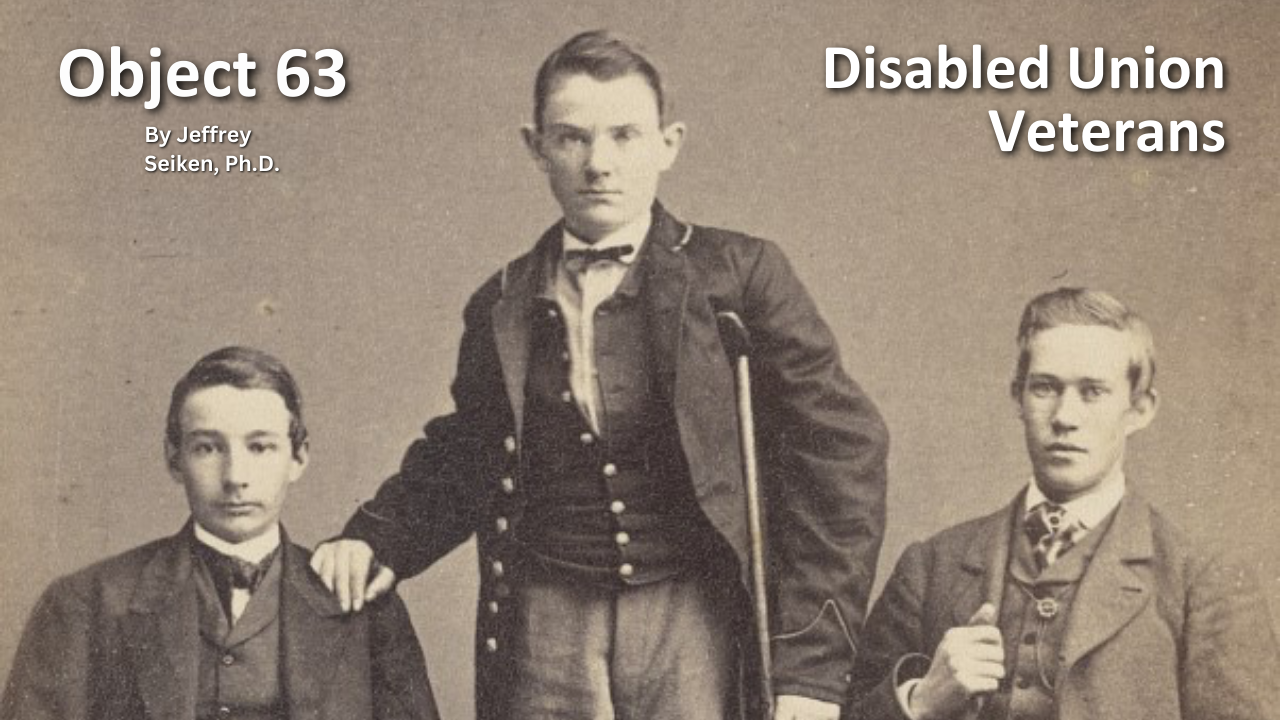

Object 63: Disabled Union Veterans

The North’s victory in the Civil War came at an enormous cost to the more than two million men who fought for the Union cause. Over 350,000 lost their lives due to battle or disease. Almost as many were wounded in action. According to Northern medical records, Union surgeons performed just under 30,000 amputations during the war. For these disabled Union Veterans, Congress made provisions to provide monetary compensation. In July 1861, lawmakers hastily passed a law for Union recruits making them eligible for the same pension allowances as soldiers in the Regular Army. Later in 1862, for the first time, a pension law explicitly granted benefits not just for men wounded in battle but also to those suffering from “disease contracted while in the service of the United States.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

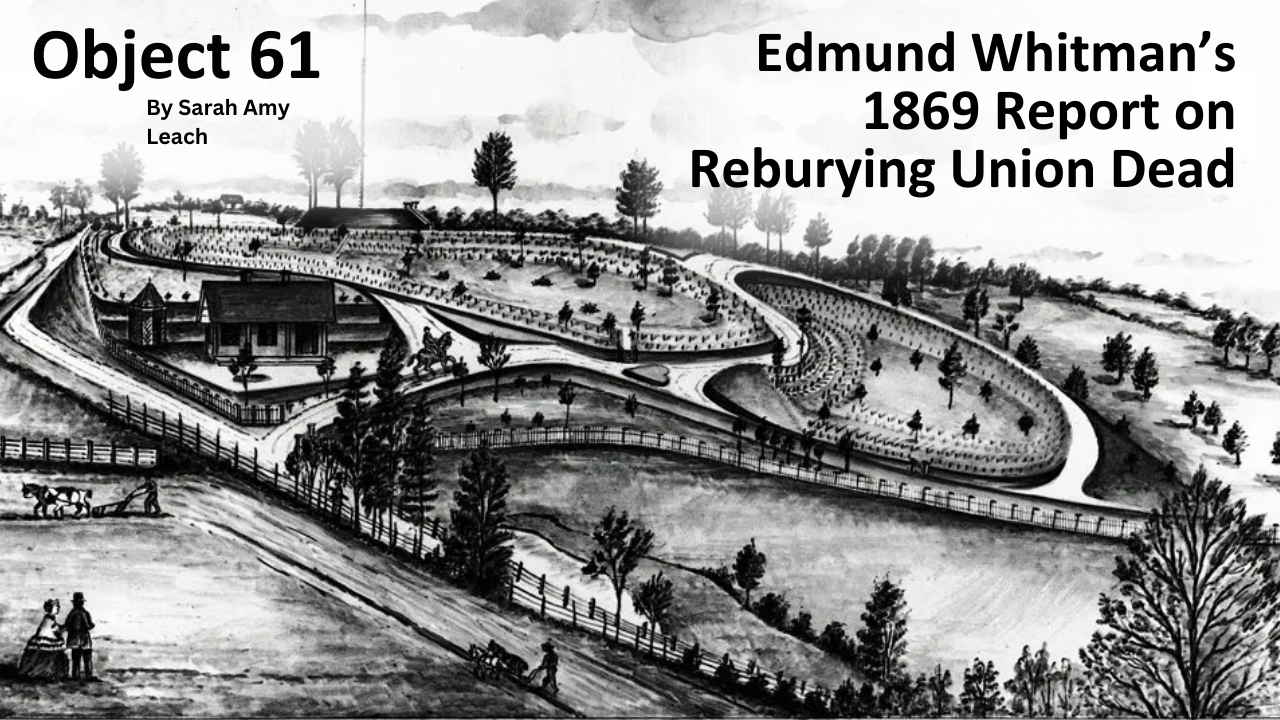

Object 61: Edmund Whitman’s 1869 Report on Reburying Union Dead in National Cemeteries

The U.S. Army’s plan for the recovery of Union dead across the South after the Civil War came about through the labors of a remarkable if little known officer, Edmund Whitman. He spent four years overseeing the collection of thousands of remains and creating “mortuary records” of reburials in new national cemeteries. After completing his “Harvest of Death,” to use his phrase, he produced in 1869 an extraordinary report that recounted the breadth, sequence, and challenges of his reinternment mission.

History of VA in 100 Objects

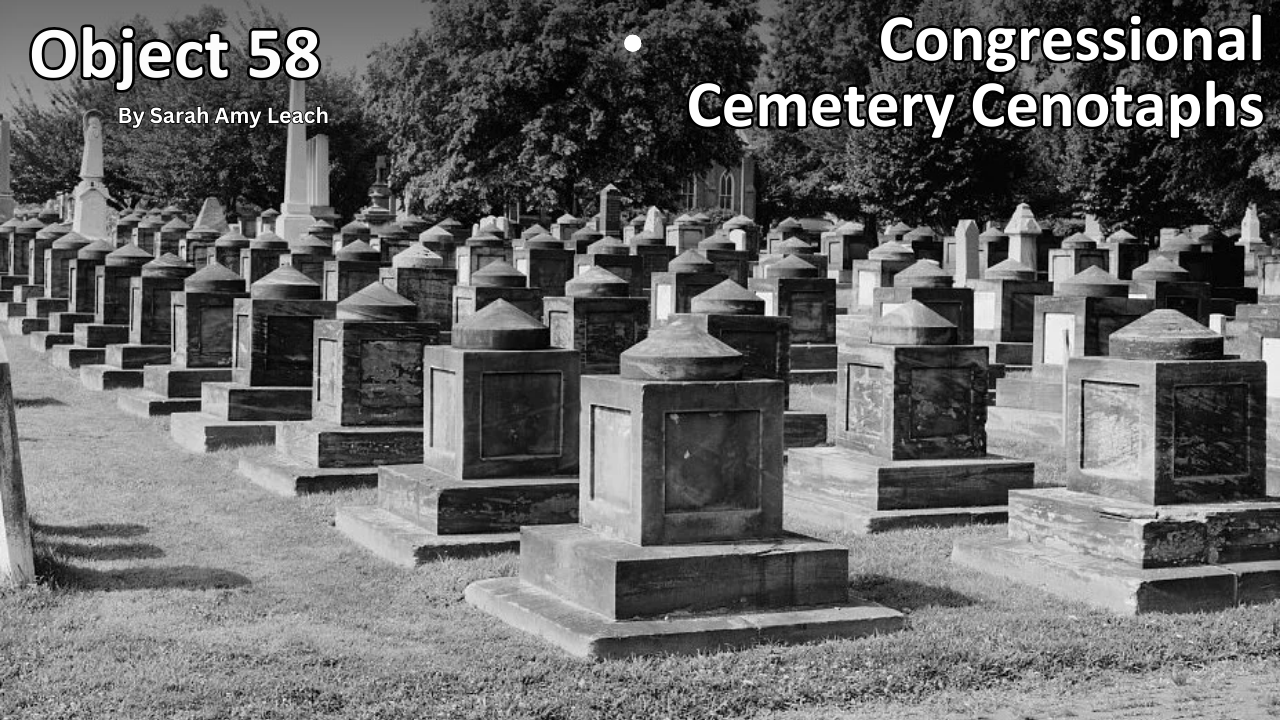

Object 58: Congressional Cemetery Cenotaphs

Congressional Cemetery occupies 35 acres of land in the southeast section of Washington, DC, and has served as the final resting place for scores of elected officials and notable Washingtonians. The more than 60,000 gravesites include 806 maintained by VA. Some 168 of the VA sites are adorned with one of the most distinctive markers to be found in the cemetery—the iconic cenotaphs designed by Benjamin H. Latrobe, the nation’s first professional architect.

Featured Stories

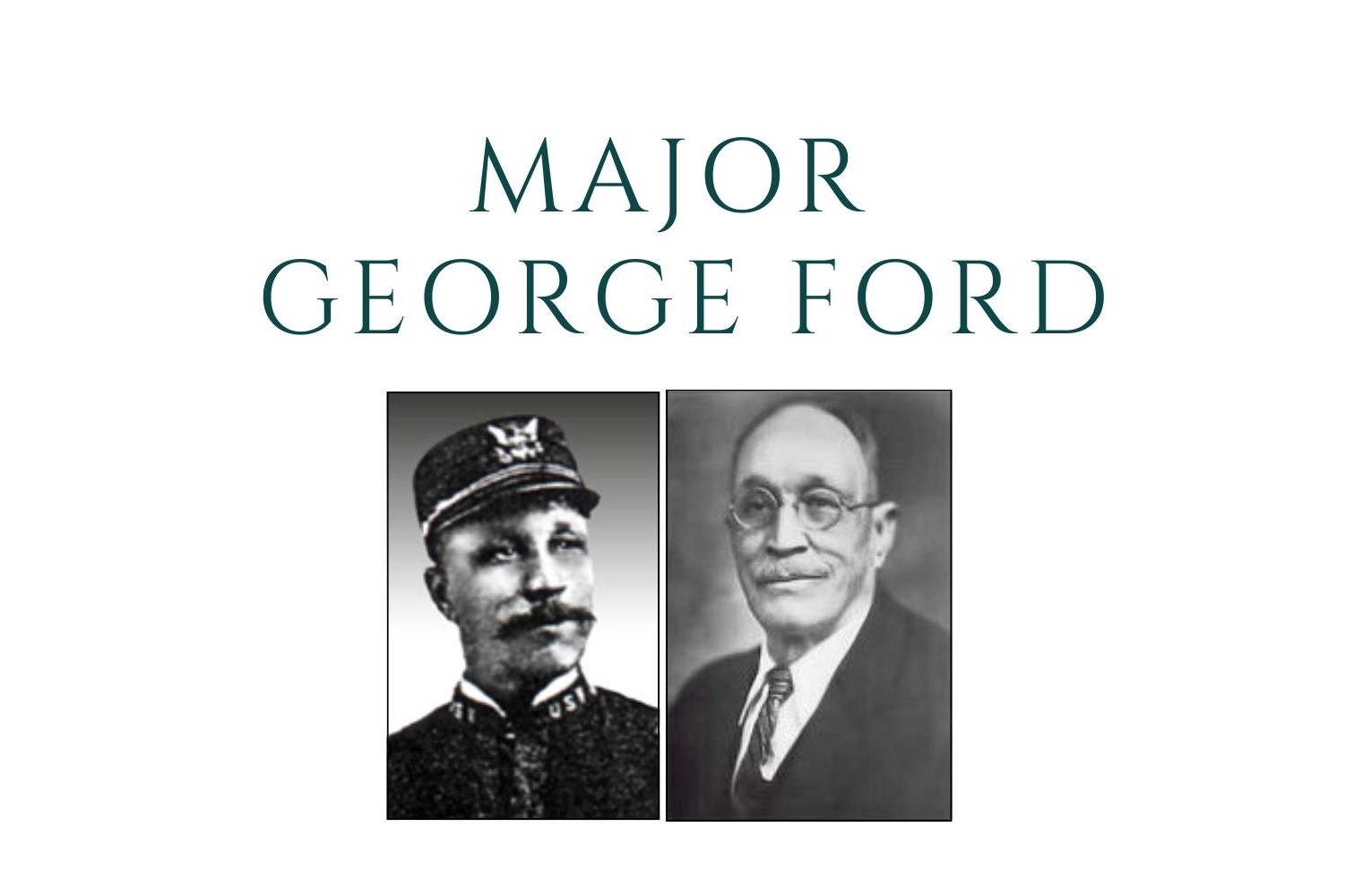

George Ford – Veteran and National Cemetery Superintendent

George Ford was a Veteran of the famed "Buffalo soldiers" after the Civil War. A U.S. law gave preference to employ Veterans to oversee the growing cemetery system for Union dead. So in 1878, Ford became one of the first Black Veteran superintendents of a national cemetery.