The federal government first began offering medical care to military Veterans in an institutional setting in the early 19th century. The U.S. Naval Asylum in Philadelphia opened in 1834, followed by the U.S. Soldiers’ Home in Washington, D.C., in 1851. Initially, only careerists with 20 or more years of service in the Navy or Regular Army were eligible for admission to these facilities. After the Civil War, the government expanded on this model of domiciliary care and created the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Over the next 40 years, the different branches of the National Home system provided room, board, and medical assistance to more than 100,000 indigent or infirm Union Veterans.

U.S. participation in the First World War produced a profound shift in public policy away from the reliance on long-term institutional care for Veterans in need. During the war, the federal government embraced a new model of Veteran welfare centered around short-term hospitalization in professional medical facilities, supplemented with physical and vocational rehabilitation to help those with disabilities return to the work force.

The revised War Risk Insurance Act passed by Congress in 1917 committed the nation to delivering “governmental medical, surgical, and hospital services” to disabled servicemembers. At first, the War Department assumed responsibility for tending to the sick and wounded. Over the course of the war, the Army expanded its convalescent capabilities twelve-fold, establishing over 100 hospitals and acquiring enough beds to accommodate 123,000 patients. The U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) supported this effort.

Founded in 1798 within the Treasury Department, PHS carried out a variety of missions to promote the health and welfare of the nation. It conducted medical research, enforced quarantines to stem the outbreak of disease, and examined immigrants at their ports of entry, among other tasks. The agency also operated some 20 marine hospitals for the benefit of merchant seaman and Coast Guard personnel. When the United States entered the war in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson ordered all PHS hospital facilities to admit patients from the Army and Navy in locales lacking a military hospital. In addition, medical officers from the PHS were detailed to the military upon request of the service secretaries.

The War Department’s plans for treating the sick and wounded were based on the premise that patients would receive up to six months of care in a military hospital, after which they would be restored to health and returned to the ranks or discharged if no longer fit for service. What government and military officials did not count on was that some servicemembers would require longer periods of hospitalization.

Furthermore, many of those discharged also needed medical care. This was particularly true for tuberculosis sufferers, who numbered over 20,000. Once the November 1918 armistice brought the Great War to a close, the Army began to dismantle its hospital system, reducing the number of beds available in general hospitals to 40,000 by May 1919 and 3,000 by October 1920.

At this juncture, the Public Health Service stepped in to fill the breach, providing hospital beds and medical care to Veterans with service-connected conditions. Besides treating the sick and injured, PHS doctors also carried out examinations of Veterans to determine their eligibility for disability compensation and vocational rehabilitation. To meet the increased demand for hospitalization services, the agency leased or purchased facilities the Army and Navy no longer wanted as well as other properties that could be used for medical purposes.

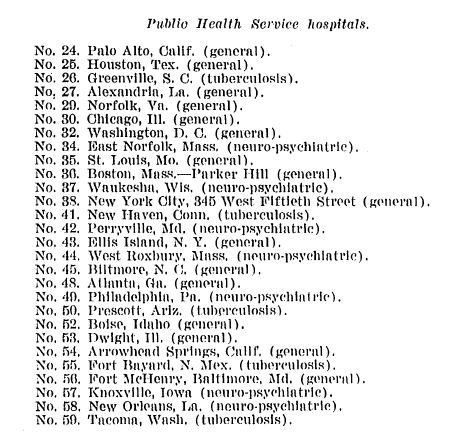

In the spring of 1919, Congress also approved the largest federal hospital construction program in U.S. history to date, appropriating more than $9 million for the building of new hospitals and the improvement of existing ones. By June 1920, the PHS reported that it was operating an additional 28 hospitals of three different types: general medical, tuberculosis, and neuropsychiatric. Agency officials asserted, however, that its medical resources still fell far short of what it needed to handle the expected surge in the number of Veterans seeking treatment over the next few years. Congress heeded the PHS’s warnings and appropriated a staggering $35.6 million for more hospital construction in two landmark acts passed in 1921 and 1922.

By the time the second of these bills became law, Public Health Service’s stewardship of the expanding Veteran hospital network had come to an end. After the war, Veterans and their advocates in organizations like the American Legion had grown increasingly unhappy with the way the federal government managed their benefits and services. Programs for World War I Veterans were spread across three separate agencies—PHS for hospital care, the Bureau of War Risk Insurance for compensation and insurance, and the Federal Board of Vocational Education for rehabilitation and job training.

The American Legion led the way in lobbying Congress to consolidate of all of these programs in a single office. The demands for reform produced the desired results. In 1921, Congress created the Veterans Bureau, an independent federal agency with expansive authority, a huge workforce, broad responsibilities, and a budget that was one the largest in the government. The following year, PHS transferred all Veterans hospitals under its control, which by then numbered 57, along with much of its medical staff to the new bureau.

Under the Veterans Bureau, the nascent Veteran health care system continued to grow. In the 1920s, the bureau established a medical research program, diagnostic centers, top-notch laboratories, and a medical bulletin. Veterans could receive in-patient treatment at one of the state-of-the-art hospitals funded by Congress or out-patient care at dozens of different clinic locations.

A further consolidation of Veterans medical facilities took place in 1930 when the Veterans Administration replaced the Veterans Bureau and took charge of all National Home properties. By the eve of World War II, the ad hoc medical program overseen by the Public Health Service for Great War Veterans had evolved into a full-service system that ministered to the health and hospital needs of all Veterans.

By Darlene Richardson, Historian, Veterans Health Administration (Retired), and Jeffrey Seiken, Ph.D., Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

Share this story

Related Stories

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 96: Postcard of Veterans Vocational School

In 1918, the government created the first nationwide vocational training system to help disabled Veterans acquire new occupational skills and find meaningful work. Over the next 10 years, more than 100,000 Veterans completed training programs in every field from agriculture and manufacturing to business and photography.

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 95: 1840 Census of Pensioners

In a first, the 1840 census collected data on Veterans and widows receiving a pension from the federal government. The government published its findings in a stand-alone volume titled “A Census of Pensioners for Revolutionary or Military Services.”

History of VA in 100 Objects

Object 94: Southern Branch of the National Home

The Southern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers opened in Hampton, Virginia, in late 1870. The circumstances surrounding the purchase of the property, however, prompted an investigation into the first president of the National Home’s Board of Managers, Benjamin Butler.