From the History Center’s archives, an inside look at how the homes were operated

Have you ever wondered where do historians, curators and archivists find all the information that goes into museum exhibits, books, and documentaries? One place is government reports. The National VA History Center preserves the history of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers as a predecessor of the modern VA. We do a lot of research related to objects from the Home and we write about what life was like for those who lived and worked there. The Annual Reports that were provided to congress are a great place to look for this information. These reports provide a great deal of information, and you don’t have to travel to an archive, can do it from your computer. See the link at the bottom to access the reports.

Congress passed an act establishing a national military and naval Asylum, and President Abraham Lincoln signed it in March 1865. The Asylum was created following the Civil War to provide a place for Union Civil War soldiers to receive medical care, housing, and support. The name was changed to National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in 1873 to clarify its function and remove stigmas connected with the word asylum. The Home served to honor the sacrifice that the soldiers made to preserve the Union.

A Board of Governors (Board) oversaw the Home system. The Board chose Branch locations and allocated the money to support them. Each year the Board submitted a report to Congress. They compiled the information provided by the individual Branches into one document. The reports contained information regarding the number of veterans supported, the expenditures made, construction, entertainment, and other information regarding the care and welfare of the soldiers, including absences and deaths. The reports offer great insight into what life was like at the Branches. They detail work done by residents on the grounds and their position in learning trades. One of the main goals of the Home was to train veterans to return to life outside the facility. The early reports list the types of workshops and the number of soldiers working there.

The early reports often mentioned the perils of alcohol consumption and its adverse effects on the soldiers. The Board chose to locate Branches some distance from the nearest town to make alcohol less accessible. “If liquors can be kept from the soldier, he makes no trouble.” This refrain that the soldiers are well-behaved if not under the influence of alcohol is a repetitive theme.

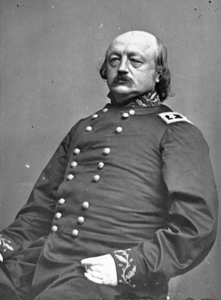

The 1870 report differs because most of it is devoted to an investigation by the House Committee on Military Affairs into the financial management of the Home. It contains testimony about how the Board allocated and expended money and chose Branch locations. Board President, Benjamin F. Butler, a former general during the Civil War, provided testimony regarding his role in selecting Branch locations and managing funds. Appendix C is a ledger of money paid to Butler that totals just over $4 million from 1866 to 1870. This amount is just under a billion dollars today when adjusted for inflation. These funds were deposited into Butler’s private account and then he would expend funds from his account on behalf of the Home. Appendix F contains the testimony of those interviewed by the House Committee on Military Affairs.

Testimony in Appendix F reveals how the Board managed the Home. It sheds light on decision-making and accounting practices. Methods accepted in 1870 certainly would not be allowed today. For instance, the Committee asked Butler about his involvement in acquiring the Hampton Road property. He acknowledged that he owned the property and suggested that the Board purchase it for a new Branch.

The Board agreed to purchase the property for $50,000. By today’s standards, that was an apparent conflict of interest. The following exchange in Butler’s testimony covered how he managed funds on behalf of the Home.

“Q. If I understand you, you have received on behalf of the asylum, from the Government of the United States, between from four and five million dollars?”

“A. That amount, plus $25,000. The following exchange covers Mr. Butler’s depositing those funds in his personal bank account.”

“Q. It was a portion of your own individual bank account

“A. Certainly.”

“Q. With nothing to distinguish it from your private account?”

“A. Certainly not.”

The testimony throughout the document reveals business practices in the 19th century. The 1870 report includes the Committee’s findings. “The general conclusion of the committee with regard to the financial management of the asylum is that the funds of the institution have been judiciously expended, …”.

The annual reports present information on the government’s efforts to provide benefits and care to veterans following the Civil War. Some current VA facilities evolved from those branches. Many elements created at the branches, including physical and vocational rehabilitation services, medical care, and burials, remain cornerstones of the benefits provided to veterans.

We use this information for different projects, including online exhibits about occupational therapy, blogs, tours and wayside exhibit panels. We are working on additional wayside panels and augmented reality tour for the Dayton VA campus, which was established as the Central Branch.

To check out all of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers annual reports, they can be found online.

By Kurt Senn

Curator, National VA History Center

Share this story

Related Stories

Featured Stories

A Brief History of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals

On July 28, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6230 creating the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA). The BVA was created as part of the Veterans Administration (VA), which had been established only three years earlier.

Featured Stories

The Fall of Saigon 1975: A South Vietnamese Military Physician Remembers

"There was chaos in the streets when I made my way to the hospital on the morning of April 30, 1975. In a place of order, there was now great confusion. The director and vice director of the hospital were gone, making me, the chief of medicine, the highest-ranking medical officer."